As a member of Bellwether’s evaluation practice, there’s nothing I love more than connecting research with policy and practice. Fortunately, I’m not alone: The National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) has launched several initiatives to succinctly describe empirical research on contemporary topics in education and encourage evidence-based policymaking.

At CALDER’s recent 12th annual conference, I had the opportunity to serve as a discussant in a session on the career trajectories of teachers. The papers in this session illustrated the potential for research to inform policy and practice, but also left me wondering about the challenges policymakers often face in doing so.

“Taking their First Steps: The Distribution of New Teachers into School and Classroom Contexts and Implications for Teacher Effectiveness and Growth” by Paul Bruno, Sarah Rabovsky, and Katharine Strunk uses data from Los Angeles Unified School District to explore how classroom and school contexts, such as professional interactions, are related to teacher quality and teacher retention. Their work builds on prior research that suggests school contexts are associated with the growth and retention of new teachers. As my Bellwether colleagues have noted, to ensure quality teaching at scale, we need to consider how to restructure initial employment to support new teachers in becoming effective.

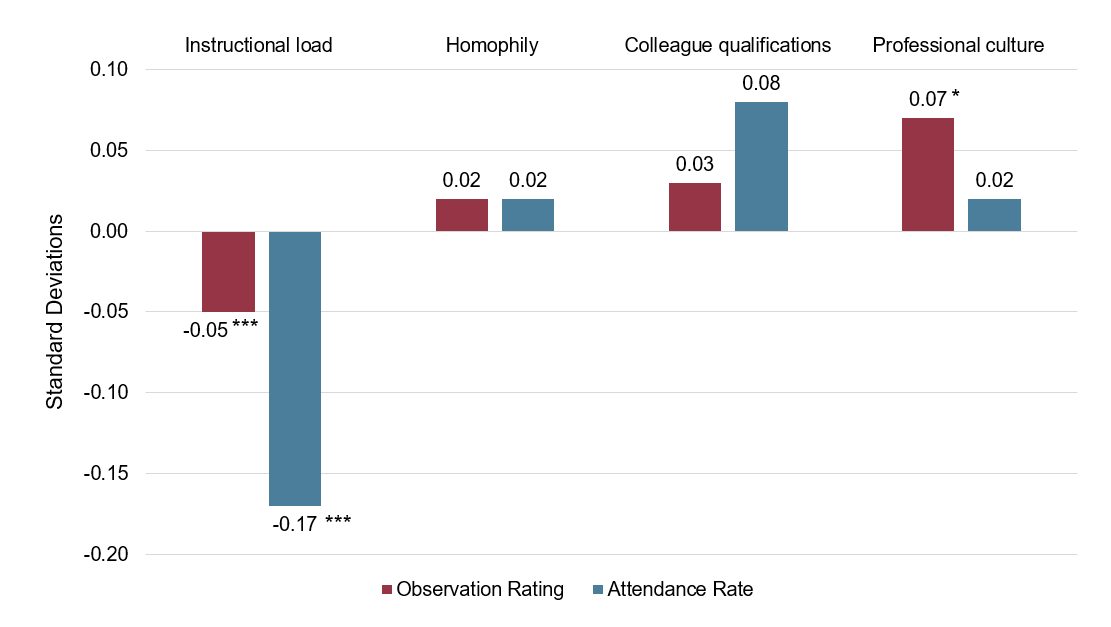

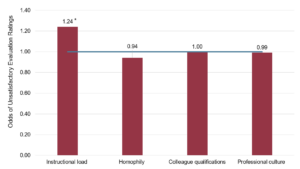

In “Taking their First Steps,” the researchers developed four separate measures to understand the context in which new teachers were operating. The measure of “instructional load” combined twelve factors, including students’ prior-year performance, prior-year absences, prior-year suspensions, class size, and the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, eligible for special education services, or classified as English learners. “Homophily” was measured by a teacher’s similarity to students, colleagues, and administrators in terms of race and gender. “Collegial qualifications” consisted of attributes such as years of experience, National Board certification, and evaluation measures. “Professional culture” was a composite of survey responses regarding the frequency and quality of professional interactions at teachers’ school sites.

Which of these factors had impact on teachers’ observation ratings and teacher attendance? As seen in the figures below, instructional load had a significant negative relationship with teachers’ observation ratings, meaning teachers with higher instructional loads (such as students with lower prior performance, more prior absences and suspensions, or larger class sizes) received lower ratings. On the other hand, professional culture had a significant positive impact on observation ratings, meaning that in schools where teachers had more and higher-quality professional interactions, new teachers received higher observation ratings. Instructional load also had a strong negative relationship with attendance rates, meaning teachers with higher instructional loads took more personal days or used more sick leave.

Figure based on Katharine Strunk’s presentation from January 31, 2019.

Figure based on Katharine Strunk’s presentation from January 31, 2019.

How to best use this evidence to inform policy and practice is unclear, for at least two reasons: instructional load is a complex construct of numerous components, and policies and practices at multiple levels shape the instructional load new teachers face. At the school level, for example, we might encourage school administrators to consider evenly distributing students with weaker prior performance or behavioral issues so that novices don’t have disproportionately challenging classrooms. But school administrators may see favorable class composition as a way of rewarding experienced teachers, in lieu of being able to provide additional monetary compensation. Similarly, at the district level, giving novice teachers preference for vacancies at schools with lighter loads is a possibility, but doing so may run counter to union contract rules regarding when teachers may apply for an open position. For example, Paul Bruno, the study’s lead author, noted that some provisions in the Los Angeles Unified School District contract privilege veterans in special cases of voluntary transfers.

In addition to considering what policies might be worth pursuing given these results, I also thought about how policymakers might interpret these findings before rushing headfirst into implementing policies. Some policymakers might be concerned that instructional load doesn’t cause teachers to perform less well, but rather that low-performing teachers are more likely to end up in schools with high instructional loads. If instructional load isn’t causing teachers to perform poorly, then reducing instructional load isn’t likely to improve performance.

In this study, however, the findings reflect a comparison between the same teacher in different years, as they experience different contexts. Because the same teacher is observed in different school contexts, we can be more confident that results are not just reflecting sorting of low-performing teachers into schools with high instructional loads. The same teacher performs better when instructional load is lower and worse when instructional load is higher. As such, these results make a compelling case that policymakers should consider addressing the aspects of teachers’ working environments, especially instructional load, when creating policies related to teacher placements.

So while developing policies to improve working conditions appears to be a worthwhile endeavor, we don’t yet know which policy options would be most effective or politically feasible. Policymakers would benefit from having a better understanding of the instructional load factors that are particularly important to address, along with information on relative costs and political feasibility of various approaches. As others have reflected, it’s important to consider the questions that may arise and what additional evidence might be needed to craft evidence-informed policy.