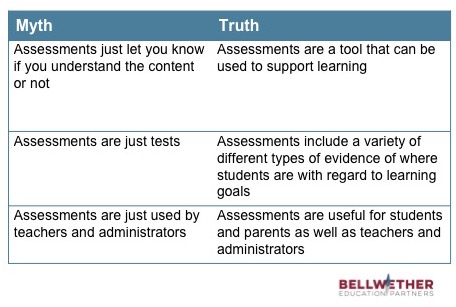

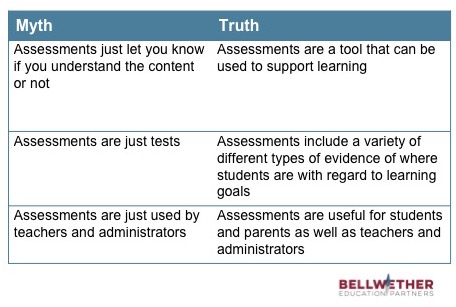

Assessments get a bad rap. Many educators express concerns that assessments are just an exercise in compliance, and especially with COVID-related cancellations, some seem ready to throw assessments out the window altogether. But during COVID-19, educators are likely to face classrooms with a wider-than-usual range of academic abilities due to disruptions in learning that occurred in the spring.

Assessments are actually the best tool to help identify and narrow those gaps between students that have inevitably widened during this pandemic, as they enable us to gather evidence about where students are in the learning progression. In developing our new book, Bridging Research, Theory, and Practice to Promote Equity and Student Learning, my co-editors and I drew on the experiences of educators across the United States to illustrate how assessments can be used to identify where students are with regard to learning goals, communicate with students and families about learning goals, and support student learning. And during COVID-19, it is even more important to take these steps to ensure that students are on the right track.

Assessments are actually the best tool to help identify and narrow those gaps between students that have inevitably widened during this pandemic, as they enable us to gather evidence about where students are in the learning progression. In developing our new book, Bridging Research, Theory, and Practice to Promote Equity and Student Learning, my co-editors and I drew on the experiences of educators across the United States to illustrate how assessments can be used to identify where students are with regard to learning goals, communicate with students and families about learning goals, and support student learning. And during COVID-19, it is even more important to take these steps to ensure that students are on the right track.

That said, assessment alone is not sufficient to enable all students to reach their learning goals. We need educators at all levels to use assessment data to inform next steps in instruction (in the classroom) and resource allocation (at the district, state, and federal level) to ensure that every student has the opportunity to meet learning targets.

Without studying assessment results and using those results to make changes to instruction, then assessment is just a compliance exercise. As my colleague Brandon Lewis has noted, ensuring that assessments are beneficial to student learning requires significant investments in assessment literacy training for educators. Most teachers don’t feel prepared to develop assessments, and others feel underprepared to interpret assessment results or communicate those results to parents and students.

Our book’s contributors include staff from state and district education agencies in California, Colorado, Maryland, Michigan, New Mexico, South Carolina, and West Virginia who describe an array of approaches to empowering teachers to use assessment data to improve instructional practices. For example, Rio Rancho Public Schools in New Mexico has developed a process to help school improvement teams formulate questions, identify the evidence needed to answer questions, and facilitate improvement plans.

In addition, the book includes insights on classroom practice from high school teachers in Kentucky and Illinois, a school administrator from a rural high school in North Carolina, faculty from teacher preparation programs in San Diego and Washington State, and a representative from the National Parent Teacher Association. Each chapter offers insights from research connected to case studies that illustrate the lessons learned from the roles and experiences across the spectrum of the educational system.

For more on some of the lessons learned, check out the video Kim Walters-Parker and I created for ResearchED’s virtual conference. I’m happy to speak to educators, students, and families to share more about the findings from our work.

October 13, 2020

Assessment Myth-Busting During COVID-19

By Bellwether

Share this article

More from this topic

Unequal Playing Fields: Disparities in Access and Funding for High School Sports

“Youth Are the Curriculum”: How to Help Students Learn Through Real-World Opportunities

Preparing Students for Life, Not Just More School: Lessons from D.C.’s Sojourner Truth Montessori

No results found.