In 2024, Massachusetts voters decided that students would no longer need to pass the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) exam in order to graduate from high school. Supporters of the ballot initiative argued that the exam was a “one-size-fits-all” test that didn’t adequately measure student achievement. However, its removal has led the state to urgently consider what, if anything, should take its place: Prior to the ballot initiative, the MCAS exam had been the sole statewide graduation requirement in Massachusetts.

Massachusetts isn’t the only state grappling over the meaning of its high school diploma. It joins a broader national conversation about what it takes to graduate high school in states across the country. While nearly all states have high school graduation requirements, some of them — like Massachusetts — are updating their practices to better meet students’ needs. Since 2020, Idaho, Maryland, New Mexico, New York, and Oregon, have all made legislative changes to their graduation requirements.

Why Do States Set Graduation Requirements?

Statewide graduation requirements establish high standards for success and ensure that all students have equal opportunities to meet those standards. Historically, state policymakers have chosen to implement two types of high school graduation requirements: high-stakes exit exams and rigorous course requirements. High-stakes exit exams are standardized tests that high school students must pass to graduate, while rigorous course requirements outline a number and sequence of core courses a high school student must complete prior to graduation. Both aim to certify that students have mastered a core set of knowledge and skills essential for college and career readiness.

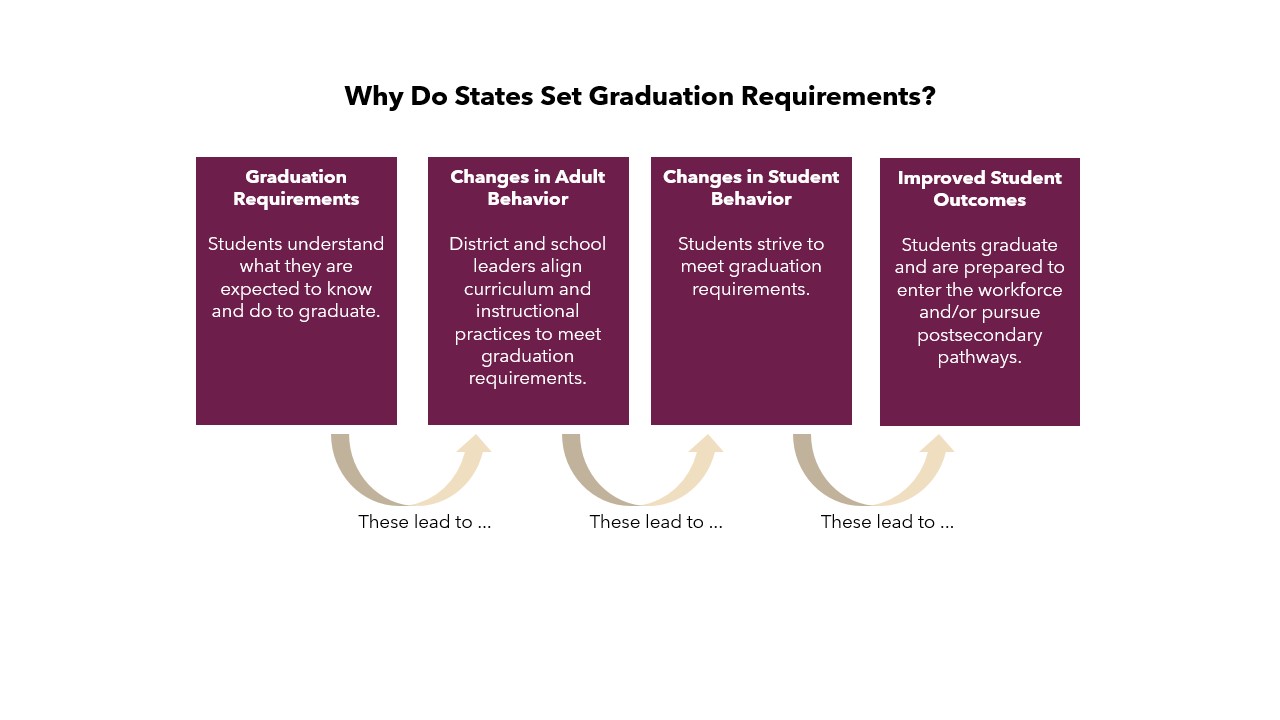

Figure 1:

State policymakers set these requirements to ensure that high school students receive their diplomas under consistent and equitable circumstances. Recent research, however, paints a more nuanced picture. Statewide graduation requirements do communicate consistent expectations for earning a diploma, but they are not sufficient by themselves to move the needle on student achievement. Improving student outcomes requires changes in human behavior by the actors in school systems — district and school leaders, educators, and students (Figure 1). Multiple research studies indicate that how states approach implementation matters when it comes to supporting student achievement through graduation requirements; there are critical differences between merely requiring students to participate in assessments or coursework and ensuring that they genuinely master the material.

High-Stakes Exams Can Measure Knowledge, But Don’t Boost Overall Outcomes

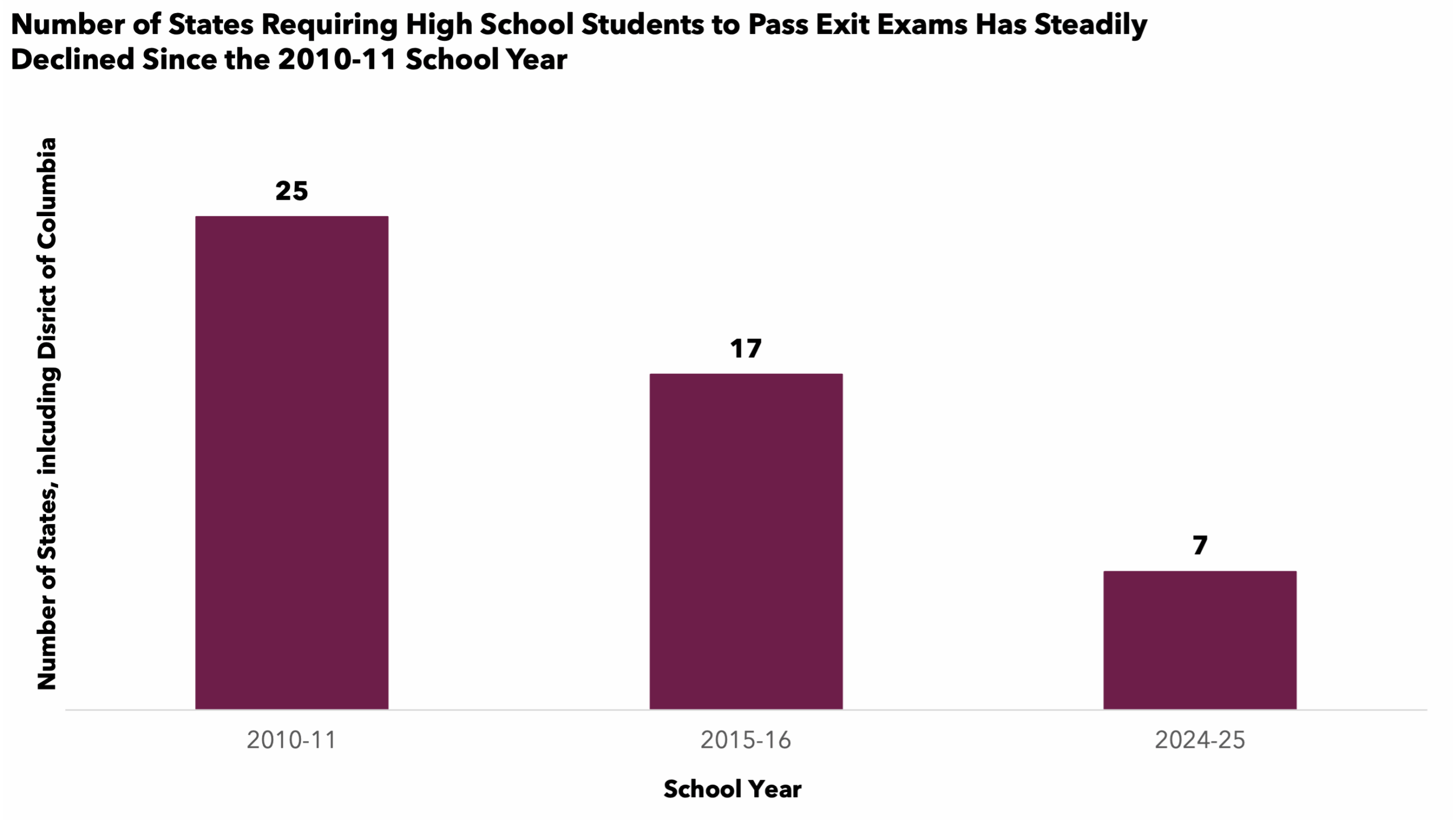

Summative high school exit exams are designed to test a student’s knowledge on a range of topics across a curriculum. All states administer summative statewide exams at least once in high school to comply with the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), but they don’t have to serve as graduation requirements. The 2001 reauthorization of ESEA, the No Child Left Behind Act, increased the federal emphasis on testing. In 2009, to improve consistency in learning expectations across the U.S., the nation’s governors and school chiefs came together to create the K-12 Common Core State Standards. By 2010, 45 of the 50 states had adopted the Common Core, and 25 required that students pass high-stakes exit exams to receive their high school diplomas.

Well-designed exit exams can indicate meaningful mastery of high school material. Multiple studies show that students who score highly on rigorous assessments frequently have better educational and employment outcomes. For instance, a 2024 Massachusetts study found that, comparing students with similar demographic, economic, and educational characteristics, those who scored at the 75th percentile on the 10th grade MCAS were more likely to graduate from high school, attend and graduate from college, and have higher labor market earnings than those who scored at the 50th percentile.

But studies have also shown that simply requiring students to take high-stakes summative assessments doesn’t boost overall academic outcomes. In fact, failing these tests can significantly harm students, particularly those at the margins. A 2013 study of more than 11,000 school districts found that newly implemented exit exams led directly to increased dropout rates, especially among Black students and those in economically disadvantaged communities who failed the tests. Similarly, research in Minnesota revealed that Black students who failed the state’s exit exam were twice as likely to drop out as their white peers who failed the same exam. This research, combined with the negative outcomes for students on the margins and a national shift away from the Common Core since its rollout in 2009, coincided with a significant decline in the number of states that require students to pass an exit exam to graduate (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Sources: CEP, 2012; FairTest, 2024

Sources: CEP, 2012; FairTest, 2024

Rigorous Coursework Benefits Students When Delivered With Adequate Supports

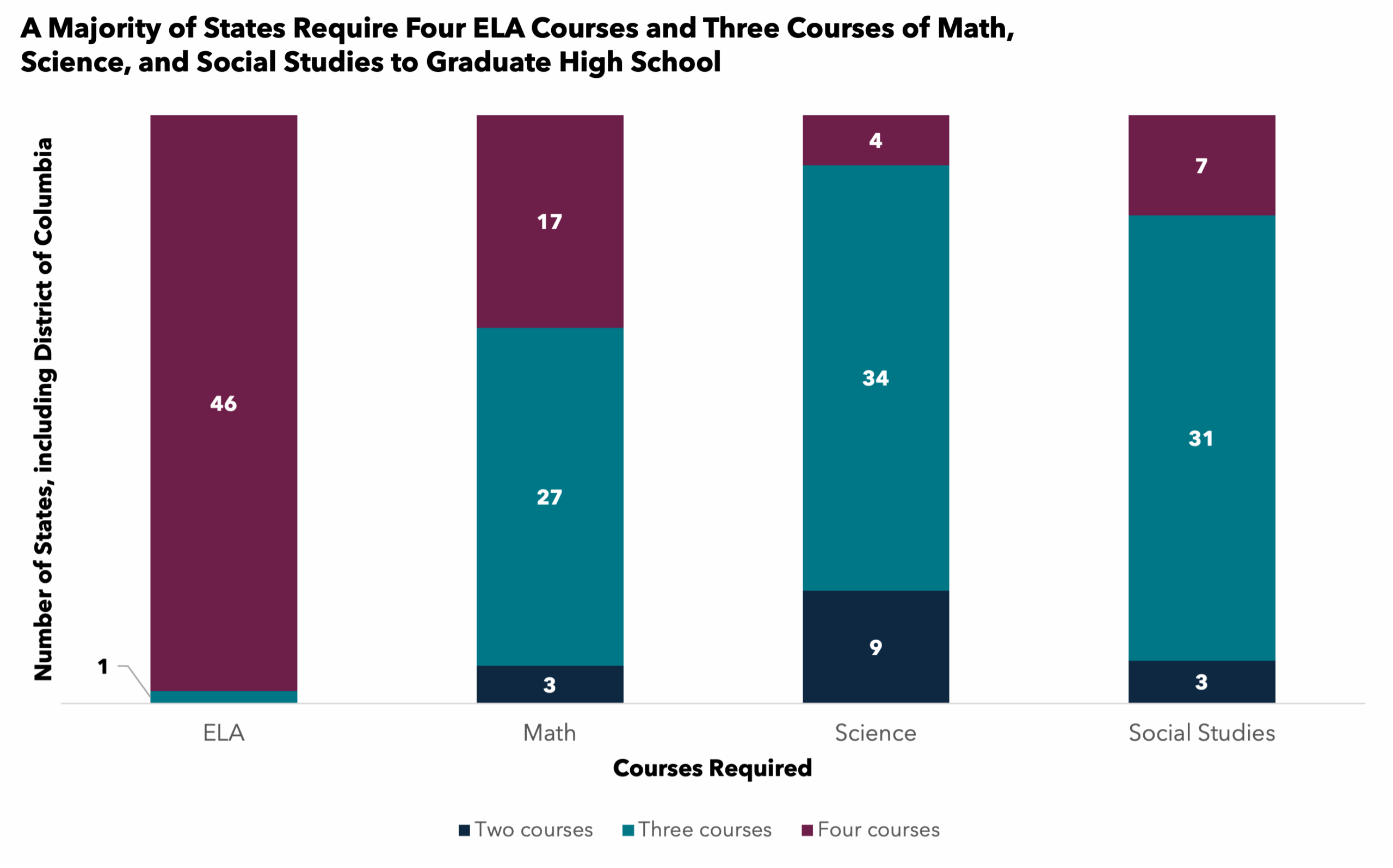

Given the limitations of relying solely on high-stakes exams, the majority of states have adopted rigorous coursework requirements for graduation (47 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia). States with course requirements consistently specify credits in four core subject areas: English language arts (ELA), math, science, and social studies (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

In contrast to the findings on high-stakes exit exams, multiple studies indicate that even setting minimum credit and course requirements for graduation can have some positive effects on both short- and long-term student outcomes. For instance, a 2022 study using national longitudinal data found that students who took a variety of advanced courses in math, ELA, and a mix of science disciplines throughout high school enrolled in postsecondary programs more often than students who did not. And course rigor matters: A 2017 study found that in New Mexico, students who took a more challenging high school course load, especially in math, were more likely to persist through high school and graduate.

Students that actually succeed in rigorous courses experience even greater long-term benefits. A 2006 study examining U.S. Census data before and after state educational reforms demonstrated that students who completed — not merely enrolled in — advanced coursework, particularly in mathematics and science, had higher rates of college enrollment, degree attainment, and significantly better career earnings than students who did not complete advanced coursework. Similarly, recent research from Texas found that Houston-area students who completed at least five advanced courses in high school were substantially more likely to earn a living wage after graduation compared to peers who enrolled but struggled or failed to finish these courses.

However, simply requiring enrollment in rigorous courses isn’t sufficient for students to reap all the benefits. Rigorous course requirements without equitable access or adequate support measures can backfire. National placement data indicate that Black and Hispanic students, as well as students from low-income backgrounds, are disproportionately assigned to less challenging courses due to systemic inequities in school funding, teacher assignments, and course availability. And Michigan’s experience mandating Algebra II illustrates the dangers of too little support: Without sufficient resources for implementation — such as trained teachers and tutoring programs — more students failed, ultimately reducing graduation rates for already disadvantaged groups.

Washington and Nevada Implemented Multiple Diploma Options, Raising Both Graduation Rates and Equity Concerns

Washington and Nevada are two states that shifted their graduation requirements in an effort to boost equitable student outcomes. In 2019, Washington replaced its single exit exam with a flexible graduation pathways model that combined increased credit requirements with tailored diploma options, allowing students to pursue academic, pre-professional, or military coursework to graduate. Graduation rates rose notably, including substantial gains among previously underserved students.

Nevada similarly shifted away from exit exams in 2018, eventually embedding the assessments into high school coursework; while there was still an end-of-course assessment, it was no longer considered “high stakes” for graduation purposes. As the state moved away from exam requirements, it established new and differentiated requirements for standard, advanced, and college-ready diploma pathways, which significantly improved graduation rates.

Yet achieving equitable gains in outcomes has been challenging for Washington and Nevada. Even though both states implemented multiple diploma pathways to support student choice on the road to graduation, early data indicates that student choices seemed to exacerbate existing inequities. Student groups that had historically been underserved tended to choose the least rigorous pathways to graduation. In Washington, nearly twice as many Black, Hispanic, and Native American students relied on waivers to meet graduation requirements compared to their white peers. Among those who did meet graduation requirements, Hispanic and Native American students were less likely to complete the most rigorous ELA and math courses. Nevada’s diploma-type data revealed similar racial disparities: Black and Hispanic students disproportionately earned the less rigorous standard-level diplomas rather than the more academically demanding advanced or college-ready diploma options.

Graduation Requires More Than Just Mandatory Participation

The most meaningful graduation requirements aren’t simply about increasing testing or enrolling more students in advanced classes — they’re about ensuring that students actually succeed. High-stakes exit exam scores and course mastery are excellent indicators of future academic and career success. However, states must move beyond mandating student participation to actively supporting student achievement. This includes scaffolding requirements with interventions, such as tutoring for students who are struggling with the material, as well as support structures, such as individualized high school counseling services for students furthest from opportunity.

Effective state-level policy will require attention to high-quality instruction, equitable access to rigorous courses, robust student support, and flexible pathways tailored to diverse student goals. It will also require targeted data collection and analysis to inform any necessary policy adjustments. As Massachusetts navigates its recent transition away from MCAS, its decisions will be an important test case for how states can rethink graduation requirements in ways that promote both excellence and equity. Ultimately, graduation policies succeed when they measure real mastery, not just mandatory participation, ensuring that diplomas genuinely reflect student readiness for whatever comes next.