Although we regularly assess student learning and evaluate the effectiveness of teachers in traditional schools, there is almost no hard data on the quality of education in the schools that serve students held in juvenile justice facilities. These facilities tend to only collect data focused on safety and security. What kind of education do these students receive?

Based on the first year of available data from the U.S. Civil Rights Data Collection, we conducted a national analysis to answer some simple questions:

- How many youth are enrolled in juvenile justice schools across the U.S.?

- To what degree do they have access to math and science courses (the only courses on which we have data)?

- How often do they enroll in these courses?

What we encountered on the way – before even answering the latter two questions – was troubling.

At the start of our analysis, we needed to set up a rudimentary fact base. How many juvenile justice schools are there in each state, and how many kids are enrolled in each? Basic questions, it would seem. Thankfully, the U.S. Department of Education collects public school enrollment nationally. In the 2013-14 data set, the first one made available, they decided to include juvenile justice schools in their definition of “public.” After adding up the number of students in juvenile justice schools for each state, we found that the number was suspiciously low. For example, Arkansas reported only six students enrolled in one juvenile justice school – in the entire state. South Carolina reported no juvenile justice schools at all.

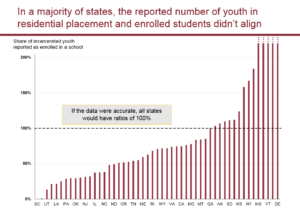

We found it hard to believe that only six students were incarcerated in all of Arkansas, so we compared the enrollment data to another data set – the number of incarcerated youth in each state for the year 2013. If all was well in the world of data quality and educational access, we would expect the data sets to somewhat align, meaning the number of enrolled youth would account for about 100% of incarcerated youth. That, in turn, would give us a fairly accurate picture of educational opportunity for incarcerated youth in each state.

However, we found that in the majority of states, the enrollment numbers of juvenile justice schools didn’t remotely match up with the number of incarcerated youth for the same time frame. In only 18 states did the number of enrolled students somewhat account for the number of youth in placement (that is account for 70% – 130% of youth). In the other states, that alignment ranged from 0% (South Carolina) to 940% (Delaware). 940% means that way, way more youth were reported enrolled in juvenile justice schools than actually incarcerated. What seems mathematically impossible is more likely the result of schools being mislabeled as serving incarcerated youth or schools reporting cumulative enrollment (how many kids enrolled in a year) instead of snapshot enrollment (how many kids were attending school on one day).

Without accurate data, it’s hard to make state-by-state comparisons about access to education in these facilities. Good data matters. Without it, we don’t know whether the thousands of kids who are reported as incarcerated, but not enrolled in a school, are actually getting an education. They deserve better.

Check out our other findings in the full slide deck, Measuring Educational Opportunity in Juvenile Justice Schools.

Alexander Brand was an intern at Bellwether in the spring of 2018.