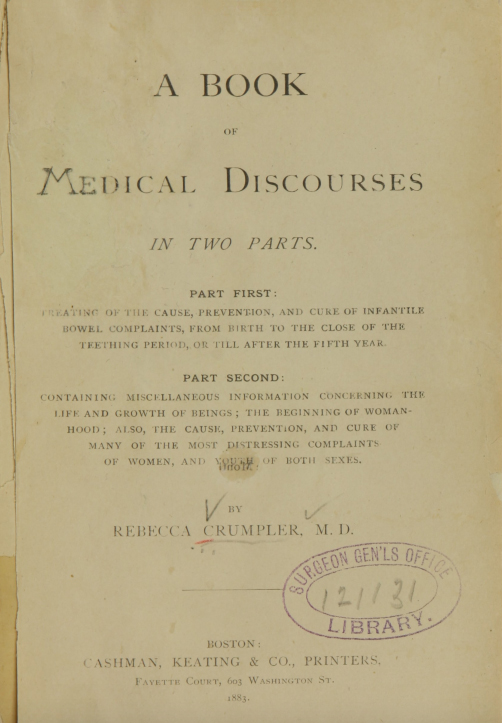

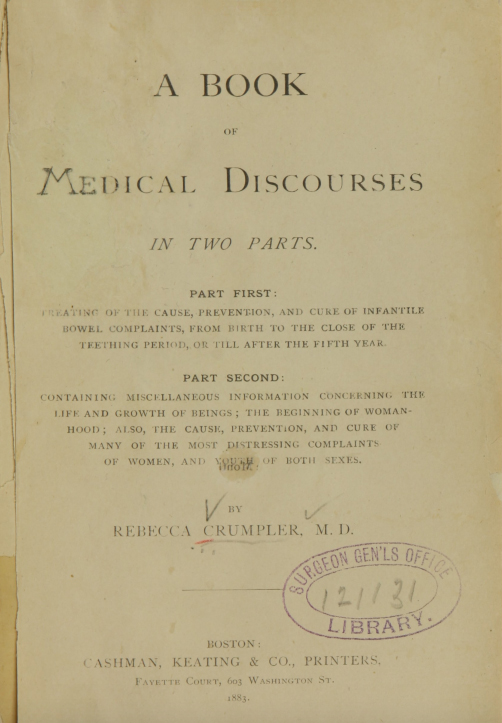

“Surely if women ask no questions of the doctors, no answers will be given.” When Rebecca Lee Crumpler wrote this sentence in her book in 1883, most doctors were male, and few were men of color. Crumpler was the first female African-American doctor, earning her M.D. degree in 1864 from the New England Female Medical College (NEFMC).

Hers was an era when women often didn’t speak if not addressed directly. And while a lot has changed, the idea of self-advocacy in medical care and medical education seems as important today as it did then: look no further than the way Serena Williams had to fight to get the care she needed when faced with life-threatening complications post-delivery.

For these reasons and more, it’s a shame that few know the name Rebecca Crumpler while Elizabeth Blackwell, the first female doctor in the United States, graduating in 1849, is well known in the history of medicine. Racism and sexism constitute a one-two blow to black women in medicine and in medical education settings.

Like many medical professionals, Crumpler recognized her interest in caring for others early on. Born in Delaware in 1831, she was raised by an aunt in Pennsylvania who spent much of her time caring for ill friends and neighbors. As an adult, Crumpler moved to Massachusetts and spent eight years working alongside doctors who wrote letters “commending her to the New England Female Medical College.” While she records this matter-of-factly in her book, one can imagine this was no small accomplishment. To receive the endorsement of white, male doctors in the nineteenth century hints at the dedication and quality of care she exhibited.

Medical school was not a requirement for doctors in the 1860s. At that time few states licensed physicians, and many entered the profession by apprenticeship with an established practitioner. But many medical schools already existed, providing a more formalized program for interested candidates. Crumpler was compelled to attend medical school to learn the most current practices in medicine and become a better caregiver.

In 1864, Crumpler took her final oral exams at NEFMC alongside two white women. A biography of Crumpler notes that the board found “deficiencies” in her education, noting her “slow progress.” The faculty noted “some of us have hesitated very seriously in recommending her.” The record suggests the strength of her earlier recommendations, and the prominence of those male physicians, may have led to her approval. It was certainly not the first occasion, nor would it be the last, that a faculty of men doubted the ability of a woman to succeed in their profession.

In 1865, Crumpler moved to Richmond, Virginia. As a Christian woman, she saw it as both a religious and professional opportunity. Richmond was “the proper field for real missionary work,” where she might learn more about “the diseases of women and children.” Working through the Freedmen’s Bureau, she wrote of serving a large number of indigent and others of different classes, “in a population of over 30,000 colored.” Although Crumpler does not write of it in her book, a later article reported that “men doctors snubbed her, druggists balked at filling her prescriptions, and some people wise cracked that the M.D. behind her name stood for nothing more than ‘Mule Driver.’” It is not surprising that her stay in Richmond would be relatively short.

The early nineteenth century “professionalization” of medicine, based on the German model of medical education, resulted in a restructuring of the United States’ somewhat haphazard system of formal and informal medical training. In the process, it dramatically reduced late eighteenth century increases of women in medicine. This setback was followed by decades of challenges to women entering medicine, including “gender-based quotas at medical schools, discrimination, sexual harassment, and a male-dominated environment.”

Crumpler stressed the importance of quality care, regardless of socioeconomic status, writing: “It is just as important that a doctor should be in attendance before the birth of a poor woman’s child as that he should be present before the birth of the child of wealth.” Were Crumpler writing today, she might alter this statement to include racial differences in medical care. Research has found black women receiving care at hospitals largely serving black patients receive lower quality care than white women receive in hospitals serving primarily white patients. As study after study reveals racial disparity in the quality of care, the importance for equity in access and quality is as important today as in Crumpler’s time.

It would take almost 160 years from the time Crumpler enrolled in medical school before equal numbers of women and men entered medicine. Today, women represent 35 percent of all doctors — but black women still only represent about 2 percent. Not until 2017 did more women than men in the United States enroll in medical school, representing 50.7 percent of matriculants.

Crumpler not only became the first black female physician, she also identified themes that are as applicable today as they were in 1864. Rebecca Lee Crumpler should be honored and remembered for her contributions, her care, and her visionary commitment to better meet the needs of patients, especially vulnerable infants and children. During Black History Month and throughout the year, it is important to honor pioneers like Crumpler and her achievements in a largely white, male profession. While much has changed in medicine and medical education since the mid-nineteenth century, the challenges faced by Crumpler are not very different today.

February 27, 2019

Honoring Rebecca Lee Crumpler, The First Black Female Doctor, During Black History Month

By Bellwether

Share this article