The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed how school districts do their work. Navigating sudden changes in large school systems is not easy but, as we’ve seen in our work across every layer of the education system this year, leaders have pushed forward innovations, created interventions, and learned invaluable lessons to reshape how districts and schools operate in the future.

In Bellwether’s recent From Pandemic to Progress three-part webinar series, leaders of school districts and community-based educational initiatives joined our team to discuss district-level planning and the pandemic’s impact on students in the upcoming 2021-22 school year.

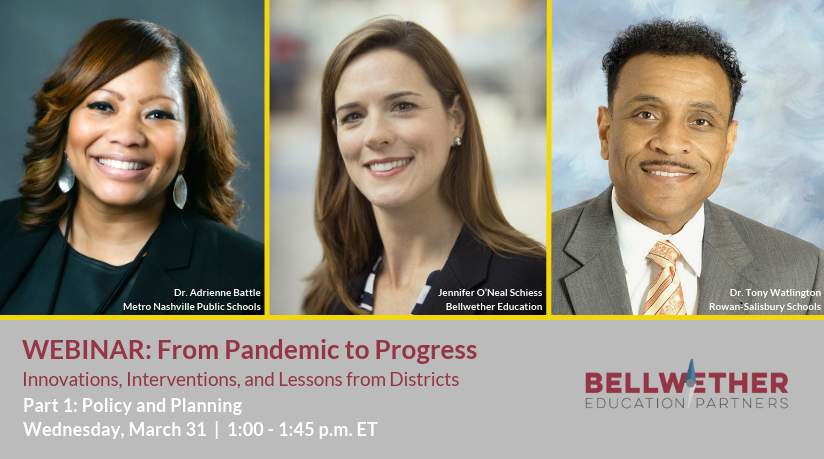

Part 1 of Bellwether’s From Pandemic to Progress webinar series focused on issues in policy and planning. Panelists shared what they’ve learned about planning and adaptability this year, their plans for next year, and how policies and funding — like the recent federal stimulus package — might affect those plans. Panelists included:

- Dr. Adrienne Battle, Director of Schools, Metro Nashville Public Schools, Tennessee.

- Dr. Tony Watlington, Superintendent, Rowan-Salisbury Schools, North Carolina.

- Facilitator: Jennifer O’Neal Schiess, Policy and Evaluation Partner, Bellwether Education Partners.

The discussion (video above) revealed four key takeaways:

Takeaway 1: Plans for 2021-22 must be adaptable and include contingencies for different modes of operation

As Drs. Battle and Watlington plan for the 2021-22 school year and beyond, both emphasized the need for flexibility, adaptability, and contingency planning built into any operational or learning plans. “We still don’t know where we will be by August 2021, so all of the contingency planning will continue,” said Battle. Creating nimble, adaptable plans for tens of thousands of students is no easy task, and Watlington compared it to, “Turning a supertanker around in a small lake.”

These plans will include options for students and families who prefer to continue learning virtually. Although both Nashville and Rowan-Salisbury had virtual schools before the pandemic, lessons from the past year will reshape existing offerings. Watlington noted changes in how his district plans to recruit and train teachers for virtual instruction and support students to be successful in virtual learning environments. The virtual school offering in Nashville, “Will look very different than it has looked in years past, because we’ve learned a lot about educating our students in a virtual space, through the lens of equity, academics, and social-emotional learning,” said Battle. However, she went on to caveat that state policy in Tennessee prevents her district from offering hybrid or virtual options for students enrolled at traditional schools once the pandemic state of emergency concludes.

Takeaway 2: Districts are looking for ways to maximize their time with students and to use time in new ways

Both district leaders discussed how they’re reframing and refocusing efforts to spend meaningful time with students. After a year in which in-person and virtual time was scarce, how can schools and districts more effectively support learning and build stronger relationships? Potential strategies to increase learning time include summer school, tutoring, and before/after school learning opportunities, all of which might involve new collaborations with community-based organizations and partners.

As a state-designated Renewal School District, Rowan-Salisbury Schools have greater flexibility over their calendar and curriculum than other North Carolina districts, and are moving towards a flexible competency-based learning model to emphasize student mastery. According to Watlington, “We are thinking differently about time and these artificial beginning and end points of 180 days per year in each grade,” and are instead considering ways to overhaul their approach to student time in a class or in a particular grade level.

Both leaders also spoke about allocating time to intentionally focus on social and emotional learning and student mental health as school communities cope with the disruptions and traumas of the past year. According to Battle, “If there’s anything that I’ve taken away from this pandemic and what our parents are demanding from us, and what our staff is capable of providing, it’s making sure that every MNPS student is known, that they’re cared for, and that we’re serving their needs properly.” Echoing that theme, Watlington said, “I am certain that this pandemic is going to fundamentally change our orientation to be more focused on social and emotional learning, and not to see it as ‘fluff’ or less than ‘academic’ learning.”

Takeaway 3: Federal stimulus money offers opportunities to fund innovative approaches or amp up resources for work already underway

K-12 school systems stand to receive $123 billion in federal funds through the American Rescue Plan. Of that, at least 20% of the funds allocated to school districts must be dedicated to addressing what the federal law calls “learning loss,” especially for subgroups of students who have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

How to use this money effectively for both pandemic recovery and educational innovation was top of mind for panelists. “We’re not going to go backwards. We’re not going to be status quo. We’re going to continue a culture of innovation,” said Watlington, adding later on, “I think it’s really important that we not squander these resources away and do the same thing we’ve done for 100 years, just because that’s the way we’ve done it.”

Federal stimulus funds will allow districts to expand and continue pre-existing programs aimed at accelerating learning, such as summer school and tutoring, and could also provide resources for big bets on innovation.

Takeaway 4: School systems must engage students, families, and educators in new ways, through an equitable lens

Panelists emphasized the resiliency of students, families, and teachers and described methods of student and family engagement that they plan to continue in the school year ahead.

For example, Nashville’s Navigator program groups students into small cohorts led by a teacher or a school/district staff member. Each Navigator maintains frequent communication with their cohort, builds relationships, and connects students to in- or out-of-school supports, as needed.

Panelists discussed ways in which the pandemic revealed inequities among students and families. Home circumstances such as internet/technology access, access to reliable health care, and parent flexibility to supervise remote learning intersected with race and class, impacting students’ opportunities to learn and engage.

District leaders pledged to carry these equity lessons into the year ahead. As his district embarked on a new strategic plan, Watlington asked himself a series of equity-related questions, including, “How do you make sure that equity is hard wired into policy? Do we have a common definition of equity? And how do you know when it’s occurring?” Similarly, Battle emphasized understanding and meeting each students’ individual needs, “We need to be able to adapt and adjust our services — our supports — specifically to the individual needs of our students, and the various communities of students that we serve.”

Stay tuned for additional summaries and videos of Parts 2 and 3 in our From Pandemic to Progress webinar series, focused on operations and outreach as well as academics and instruction.