In recent weeks, Democratic presidential candidates’ views on education, specifically on school choice and charters, have come under scrutiny. And a recent EdNext poll indicates that Democrats are deeply divided on school choice topics.

The usual debate on school choice asks “does it work,” but rarely do I hear discussion about how it’s intended to work in the first place.

Some people view school choice as a public good in and of itself, in that it provides options for families. For this group, evidence of student achievement, educational attainment, and other outcomes is secondary. It is the availability of and access to educational options — on their own — which validate the need for and merit of school choice.

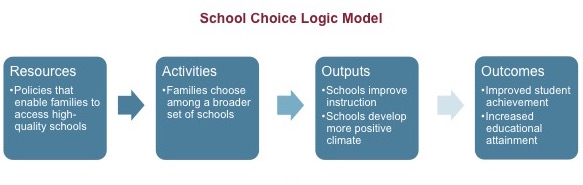

Others, myself included, view school choice as a potential means to an end: a way to improve educational opportunities not just for the students whose families are willing and able to choose, but for those students who remain in their traditional public schools as well. In theory, competition pressures schools to improve quality in order to retain their “customers,” i.e., students.

In order to get from point A (offering school choice) to point B (improved outcomes), what has to happen? The logic model below outlines the theory behind my perspective:

A recent meta-analysis of school choice concluded that competition resulting from school-choice policies has a very small positive effect on net student achievement in a district. And a recent school choice summary from Mathematica and review of three decades of charter school research from Annenberg Institute had similar findings. While small positive effects on student achievement are promising, the authors of the meta-analysis caution against overstating the impact of competition, and conclude that “the effects are too small to have a major impact on educational quality and inequality on their own.”

Given this small impact, what might be done to enhance the steps in the logic model? Here are three ideas to strengthen school choice:

- As my colleagues have noted, healthy markets depend on good information. Families need good information about their school choices — not confusing information — and a highly publicized and streamlined school application processes. They also need access to robust transportation options in order to access choice.

- Charter and district-run autonomous schools need to test innovative approaches and share results with other schools in the system. If schools of choice test innovative approaches but don’t share their successes and failures, other schools cannot learn from them.

- Accountability policies need to motivate schools to actually be good rather than just look good. If schools of choice focus on marketing to attract students (and the accompanying per-pupil funding) or engage in admissions and retention practices that result in self-selection of the students most likely to make gains, it’s unlikely that school choice will be a “tide that lifts all boats.” Charter authorizers need to ensure that charter schools are high quality, both in terms of instructional quality and school climate. Authorizers might consider limiting the growth of schools found to be less effective at improving student achievement, such as online charter schools, while giving strong schools the opportunity to expand.

Of course, that brings us back to the initial tension: for some, choice itself is a good, and limiting choice is not a desirable outcome. Others (myself included) would argue that since the public subsidizes education, publicly elected officials should play a proactive role in promoting high-quality educational opportunities that maximize student achievement and educational attainment. In other words: choice alone is not good enough.