The latest release from ROCI, our rural-education project, (‘Innovation Amid Financial Scarcity: The Opportunity in Rural Schools,” by school finance expert Marguerite Roza) sheds light on this subject.

Image from www.stltoday.com

Though rural-schools policy and K-12 finance formulas aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, Roza’s work is exactly the kind of report most consumers of edu-research want. It provides data in an important area currently dominated by conjecture; it asks and answers an intriguing new question; and it presents a completely unexpected finding that can serve as the launching point for future research.

The paper begins by discussing the funding levels received by rural districts relative to non-rural districts. Many believe that rural schools are dramatically underfunded because they lack the clout of their rural and suburban peers and the economies of scale necessary to make the most out of their resources. Those familiar with school funding formulas know, however, that at least some states “plus up” rural districts in a number of ways (e.g. special rural-schools programs, appropriations line items for rural-school staff).

Roza’s analysis shows that both are true. Most, but not all states, “have structured their state education finance systems in ways that ensure rural districts receive more funds per pupil than do their more centrally located counterparts.” However, relative funding levels vary significantly state to state.

In California and Georgia, smaller districts receive about 15 percent above the average per-pupil spending levels in their larger-district peers. In 12 states, small districts get a bit extra; in Minnesota and Wisconsin, they get amounts almost identical to larger districts. But in 12 states, small districts operate with fewer dollars than the state’s per-pupil average.

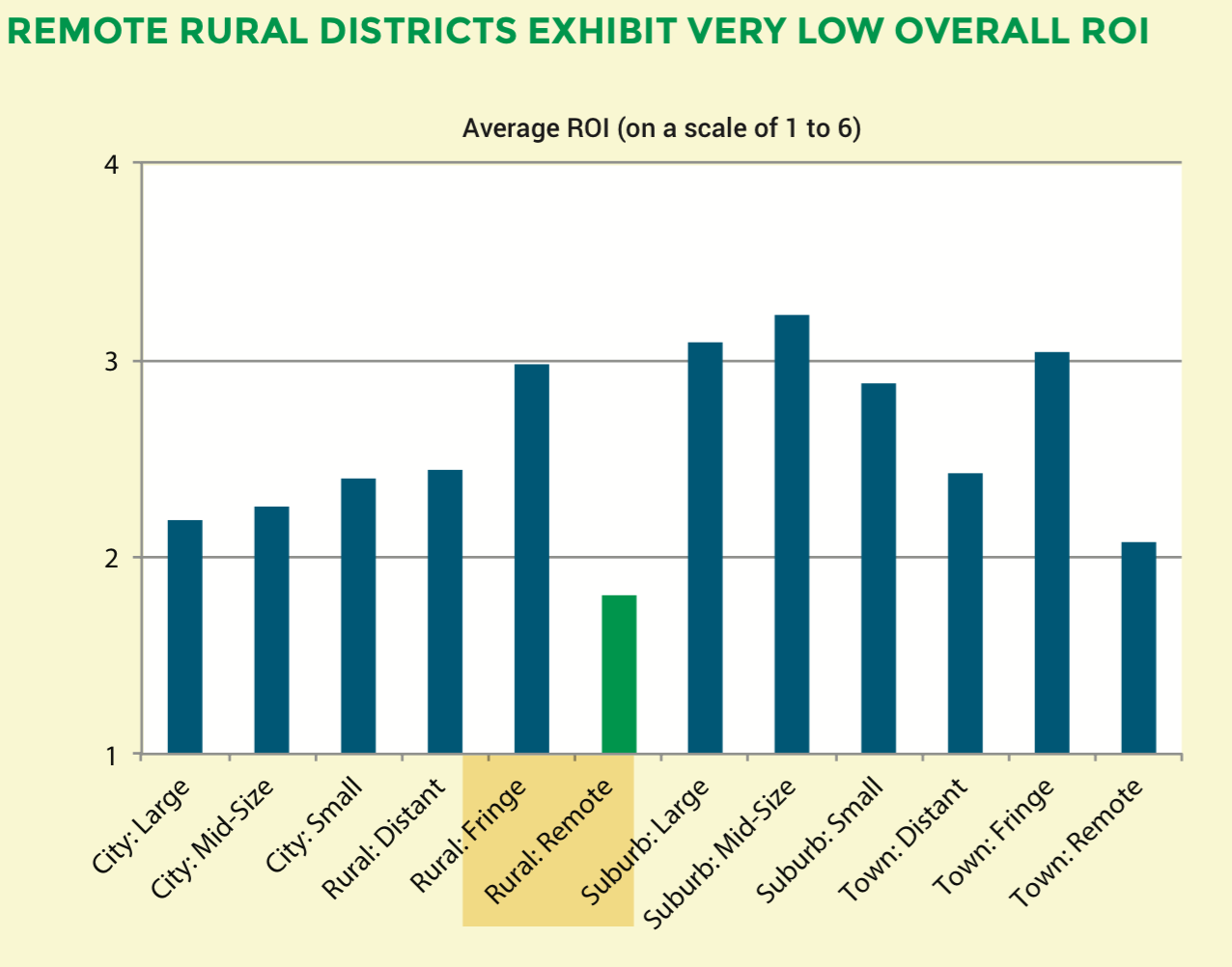

Though these descriptive statistics are illuminating, the big question Roza tries to answer relates to “return on investment” (“ROI”), what kind of academic results do rural districts generate with the funding they receive. The conclusion isn’t encouraging when it comes to the districts farthest from populations centers: In the author’s words, “Remote rural districts exhibit the lowest average ROI among any sector.” Even when remote rural districts receive more per-pupil funding, “the outcomes aren’t any better on a relative basis…there doesn’t appear to be a clear payoff for overfunding remote rural districts in terms of student outcomes.”

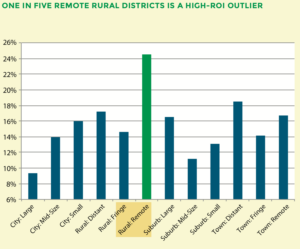

Then comes the truly surprising finding. Even though, on average, remote rural districts aren’t producing comparable student-learning results for the funding they receive, “it turns out that the odds of being a super-high-ROI district are highest if the district is a remote rural district.” In other words, there are a significant number of remote-rural districts that are positive ROI outliers. Somehow they are generating enormous academic bang for the buck.

The paper doesn’t go searching for the “why” (that’s the subject of Roza’s year-two paper). But the author does offer some hypotheses based on interviews. Some suggested the explanation lies in the ability of some districts to “leverage their rural context to their advantage,” for example, capitalizing on the strengths of specific staff members. Roza recounts hearing that one remote district found a personal trainer to work with students instead of hiring a full-time PE teacher.

The paper doesn’t go searching for the “why” (that’s the subject of Roza’s year-two paper). But the author does offer some hypotheses based on interviews. Some suggested the explanation lies in the ability of some districts to “leverage their rural context to their advantage,” for example, capitalizing on the strengths of specific staff members. Roza recounts hearing that one remote district found a personal trainer to work with students instead of hiring a full-time PE teacher.The paper ends with helpful recommendations, including the overarching suggestion that state governments “view the challenge for rural districts as one of harnessing the independent, nimble, and entrepreneurial spirit of rural communities, and empowering rural districts to innovate toward improved services in the context of limited resources.”

The gist is this: “The worst thing a state can do is put a stop to whatever innovation is happening.”

More specifically, the paper recommends that states do a better job of documenting and disseminating the practices in super-high-ROI rural districts; allocating funding based on students and student characteristics (not staffing expectations or other input requirements); and eliminating rules related to district service delivery.