The gloss on this AFT poll is really something. There is some good news, but it’s also not hard to discern fault lines.

School transportation – needs work! And here’s an analysis from BW of emerging trends around choice policy.

NAPCS out with a new ranking of charter school laws.

Here’s Roza on the Julia Keleher situation.

Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona laid out his vision for education on Thursday.

Our students’ success is at stake. Not just the students we serve today, but also those who have yet to be born.

Our country’s strength is at stake.

Our status in the world is at stake.

At some level that’s always true isn’t it? It’s a cruel world. But can we talk about any issue in anything less than apocalyptic terms now? In any event, people loved it. Randi Weingarten said, “The secretary’s remarks were brilliant and inspiring in their practicality about how to support kids and their families as well as schools and educators right now.” Dan Domenech of AASA merely said he was “pleased” and “could not agree more.” Ordinarily that counts as appropriate praise. In today’s environment of praise inflation and against “brilliant,” Dan’s basically trashing it.

In fact, the speech was more or less the Dem wish list on education with an extra overlay, excuse me dosage, of tutoring. Cardona’s push to have students participate in extracurricular activities is interesting and is a practical idea to increase connection. (With the amount of federal money sloshing around every kid can have their own team or club). He called out some other important issues, including mental health. Overall, though, it’s unclear Dems really get the message voters are sending: they are not interested in a party of the system but rather one that can stand astride and is going to make it work better. Responsiveness to parents needs more than a bullet point.

This Times article about Asian students in specialized high schools is excellent. Recommend. And this line is perhaps the Platonic educational mad lib:

Critics of specialized high schools argue that these institutions are out of step with the zeitgeist and educational practice.

Critics of ___________ argue that these ____________ are out of step with the zeitgeist and educational practice.

Basic skills testing, open classrooms, closed classrooms, vocational education, requiring Greek and Latin, phonics, whole language, proficiency standards, traditional math instruction…

Among the many reasons our schools are screwed up, attention to zeitgeist has to be high on the list. In education, it’s a fancy word for fad.

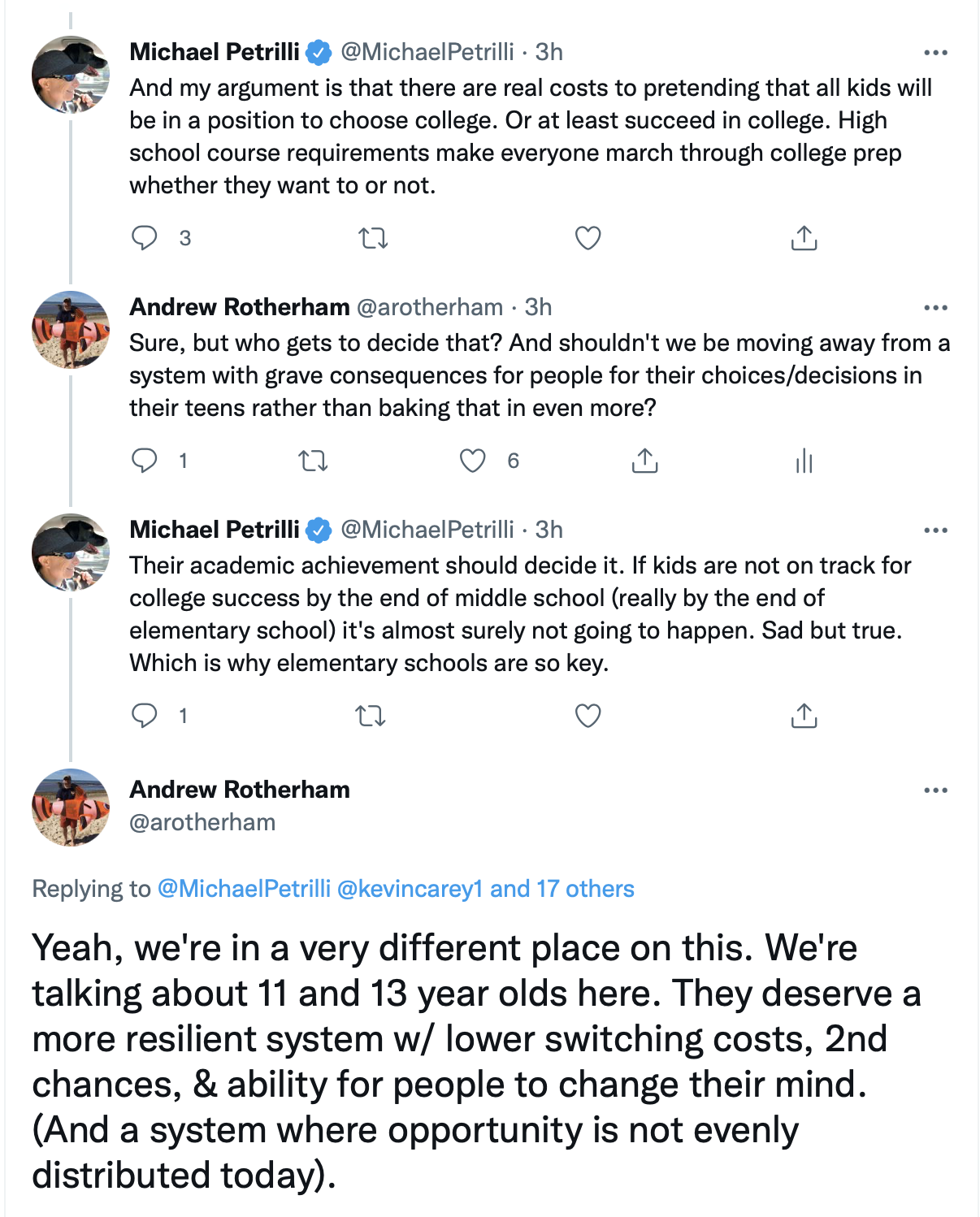

There was (and is) a debate on Twitter about “pathways,” per this article. Here’s one piece:

This is an important issue to discuss, but I worry that in an effort to show tough minded realism some reformers are focusing on the kids rather than the system. Sure, academic achievement should have consequences. So, for instance, I dissent from the now popular idea that the path to equity is to dismantle test-admissions public schools or limit who can take advanced classes. Those are a good option for some kids and an appropriate bar at that age. Yet overall, young people should be on a trampoline that helps them bounce toward different things and then bounce again as needed, not a fixed or irreversible pathway.

Other than perhaps Social Security, college completion for low-income students is the best anti-poverty policy we have. Yes, choice of college and major matter and all that. But we should be encouraging and supporting low-income kids to go to college not trying to talk people out of it. Are there rewarding careers and rewarding lives that don’t involve college. Of course. The question is who is doing the choosing and why.

A more normative point, I like the second chances the American system offers. Yeah, it would be great if so many kids didn’t need them. Still, it’s a good feature of our system that we don’t set permanent gates based on tests or put kids on fixed paths. This whole idea of deciding who is college material is a fraught business. And why anyone thinks it’s a good idea to trust a system, a system that fails at some of its most basic responsibilities, to make high stakes determinations about people’s lives escapes me? Empower people to make their own choices.

PreKatastrophe?

Studies that don’t show pre-K effects sure do get less attention than ones that do! There is a new study from Tennessee rattling around. It’s behind a paywall, but pre-K skeptics sure seem to know where to find it.

The analytic sample includes 2,990 children from low-income families who applied to oversubscribed pre-K program sites across the state and were randomly assigned to offers of admission or a wait list control. Data through sixth grade from state education records showed that the children randomly assigned to attend pre-K had lower state achievement test scores in third through sixth grades than control children, with the strongest negative effects in sixth grade. A negative effect was also found for disciplinary infractions, attendance, and receipt of special education services, with null effects on retention.

Yes it’s just one study so all the usual caveats apply. But the overall research on early-education is not the slam dunk you hear from advocates. So this new study is much less an outlier than it seems – both on the TN program and more generally. It just seems shocking. That’s because you’ve probably been told for years that the evidence on pre-k is exceptionally strong, as strong as anything we’re often told, so anyone who doesn’t think we should just airdrop federal pre-k funding on pallets is a jerk who hates little kids, poor families, and probably most of all little kids from poor families.

Still, you’re going there this study come up in the BBB debates. Should it be a nail in the coffin of early ed funding? I’d suggest it’s more of a reason for caution. Of course, I think ensuring access to pre-k for all kids is a good child care, workforce, and education policy for a few reasons. So you should take my take with that in mind.

Quality pre-k needs quality elementary (and secondary) schools as well. Fade out has never seemed like a big surprise given other feature of the elementary and secondary system – eg gaps get bigger the longer kids are there. This study, though, is about more than fade out.

The effects here are varied, and sometimes statistically significant but not enormous. For instance, attendance rates were 97.5% of the treatment group vs. 97.1% of control in 6th-grade and retention differences were negligible. The special education outcomes were more notable. And the students in the untreated group were not just sitting around, a third were in some sort of formal early ed setting. As with some of the class size research we should also be skeptical this is all as random as it appears – it’s a natural experiment. Scarcity often creates the conditions for education experiments, it can also complicate them because these are human systems.

Here are the test scores, the differences there are real:

Finding no effects and fade out is one thing, finding harm is different. And should make you wonder what’s going on at a few levels. Perhaps it is study issues. Or there is speculation that the TN program is low-quality and explains this. And some people think that low-quality early-ed experiences, especially for very young children, do actually create longer term harm. In other words, something might not be better than nothing.

Everyone generally agrees the quality of a lot of early education is not very good. That’s why plans to balloon spending on ECE without a lot of attention to quality and scale will fall short substantively (and probably imperil Democratic efforts to fund big initiatives down the road). It’s hard to scale in general and the evidence makes clear pre-k is not only isn’t an exception, it may be much harder than average. That these studies don’t consistently point the other direction should cause concern. Still, there are a lot of reasons from education, family, to workforce why expanding access to early education for low-income parents who want to choose it is a good policy. And a policy we should research more.

Can you read what I’m saying as ‘damn the evidence, here’s what I want?” Perhaps. I’d argue it’s more we should engage with the evidence honestly but policies should be considered in a broad frame and early ed cuts across a few dimensions.

Nothing compares to a Prince song?