Hundreds of thousands of people are released from state or federal prison every year, and nine million more leave local jails. On the whole, very few people serve life sentences, and at least 95% of prisoners ultimately return home.

In 2016, the Obama administration designated the last week of April as “National Reentry Week,” an attempt to bring public attention to the challenges facing people who return to their communities after incarceration. It doesn’t look like the Trump administration is upholding the designation — the Department of Justice’s site was archived — but last month, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos unexpectedly visited a youth correctional facility. There she spoke about the role that high-quality education programs play in supporting successful transitions back to community life.

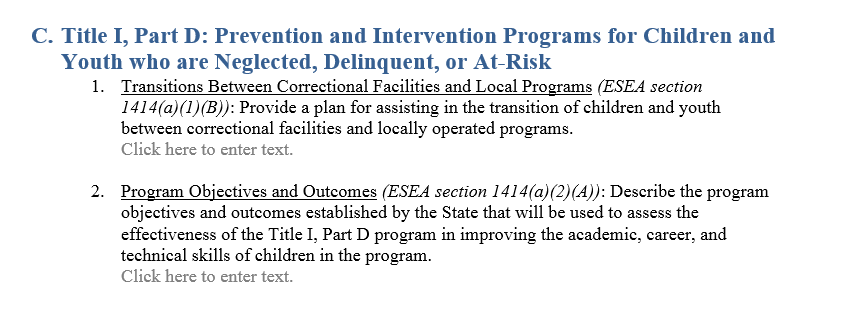

It’s time that educators took the lead in creating substantive policies to support previously incarcerated people as they rejoin their communities. For young people, the move from a secure school back to a community-based program is a crucial moment when students are at risk of losing their earned course credits, experiencing barriers to enrollment, and dropping out entirely. I’ve recently shared data on the importance of this transition. And, for the first time in history, this moment is called out in federal education law: The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requires states to develop plans to support that transition. And not only is it in the law, it even made it into the final federal template:

Screenshot via U.S. Department of Education ESSA template.

While this is big, we should also recognize that progress could be bolder; this section will not be evaluated in the official peer review process, and the guidance says simply that it “will be reviewed by staff at the Department.”

And the news coming out of states suggests that they aren’t taking full advantage of this opportunity either. Of the plans submitted so far, most describe goals and strategies for transition plans that are cursory and vague (or both). One describes a committee that is planning to develop a plan. Another gives staffing levels that are woefully insufficient to meet the need — one transition specialist for an entire agency. Almost all describe a lack of good assessment tools to properly track achievement. Of course, doing something is better than nothing. But the problem has rarely been that states are truly doing nothing, it’s that what they are doing doesn’t work. Researchers estimate that upwards of 60 percent of young people who are incarcerated will never successfully return to school.

This opens a unique opportunity for state education advocates to push their education leaders to do more. DeVos’s visit, coupled with the explicit language in ESSA and in the federal template, suggests that this discussion — long relegated to the dusty corners of corrections reform — may have finally, firmly found a foothold in federal education policy.