Before digging into the research on Chicago’s education system and talking to many of the city’s leaders for a current project at Bellwether, I categorized the district as largely traditional with a decent sized charter sector. What I learned was that Chicago has more school types and school choice than I realized, especially at the high school level. It turns out that while most of the headlines regarding the district have been about scandals and violence, a lot of people have been focused on making sure more kids go to better schools faster.

That fact was reinforced when I looked at a recent report from the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research on the first round of applications and offers from Chicago’s brand new high school unified enrollment system. Neerav Kingsland provides a good take on the results. I just want to reiterate one point and add a few more observations.

Screenshot via https://go.cps.edu/

Neerav points out that Chicago Public Schools’ (CPS) school information and application website GoCPS is easy to use. I can’t reiterate that enough. It’s insanely intuitive and informative. When I was making school choice decisions for my son in San Francisco earlier this year, I had to toggle between Google Maps, a PDF with school information from the district, and school performance information that I collected and analyzed myself. GoCPS has a map-based interface that provides the all information parents need, and it would have given me everything in one place. Why don’t more cities with school choice have a similar platform?

On a different note, the Consortium report notes that CPS has approximately 13,000 surplus seats in the district, an oversupply in other words, which might lead to more school closures and mergers. In addition to creating easier and more equitable enrollment processes for a district, unified enrollment systems provide detailed information about parent demand (and lack thereof). School closures have been painful for CPS in the past. The unified enrollment system now gives CPS CEO Janice Jackson more information to make changes that reflect the preferences of the district’s families and, hopefully, make difficult decisions a bit easier.

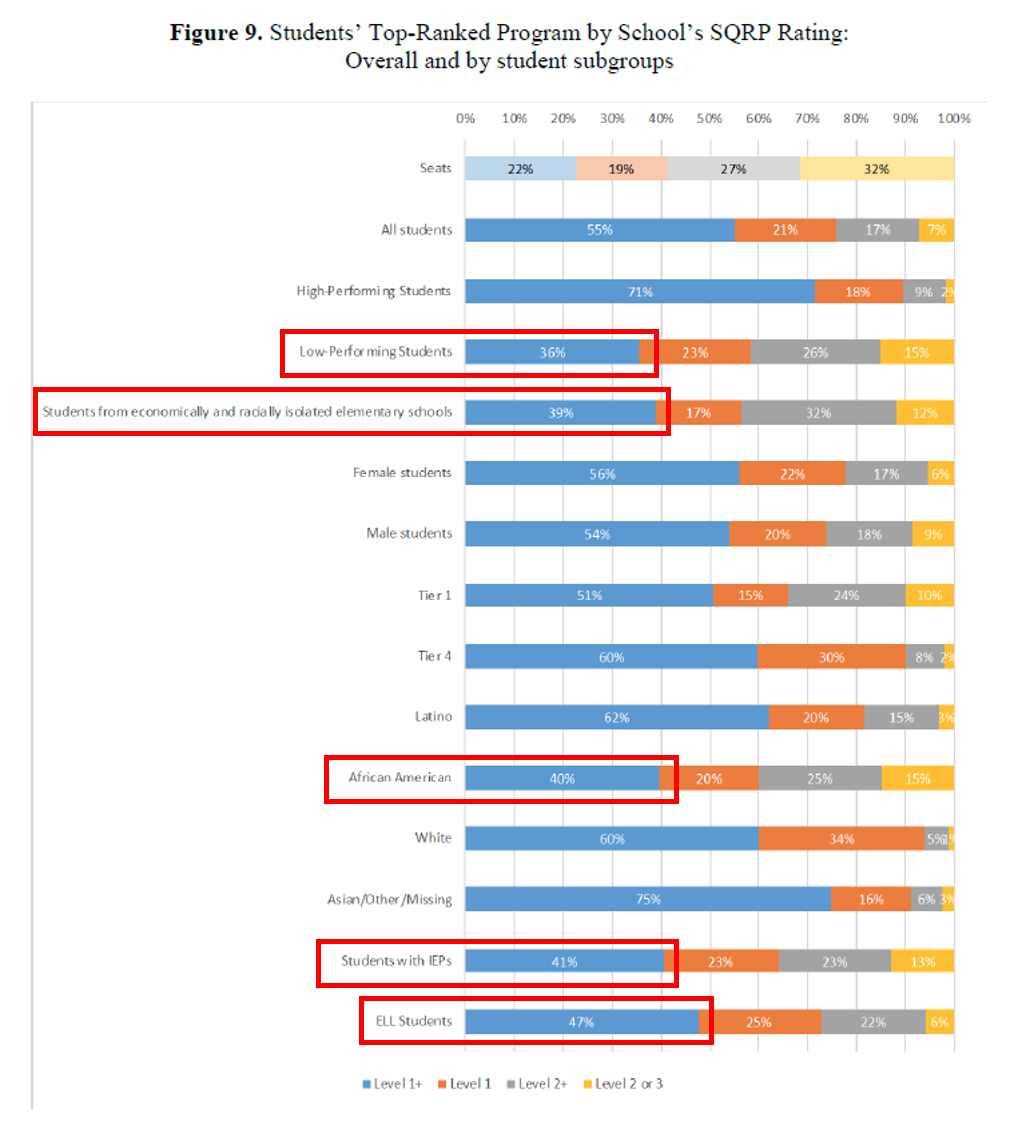

Neerav also points out that families rarely rank the lowest performing schools as a first choice — a fact he interprets as families making choices based on school performance. I agree but I see something troubling in the same graph:

https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/gocps-first-look-applications-and-offers

Low-income students, low-performing students, English Language Learners, students with special needs, and African American students ranked the top-performing schools lower than other subgroups. The Consortium researchers made the same observation and call for more research. I agree. It’ll be important to know whether this difference is because of inadequate communication about school choices or quality, parents preferencing lower rated schools closer to home, or some other reason altogether. (The question is ripe for human-centered investigation.) The answer will help system administrators decide how to allocate scarce resources.

I can’t say this enough: the University of Chicago’s Consortium for School Research is a remarkable institution providing high-quality, actionable, relevant, and timely research for Chicago’s education leaders to use while making high-stakes strategic decisions. Every big city should have a similar outfit.