As states grapple with how to fund colleges and universities in an equitable and sustainable way, several are revising their higher education funding formulas. These formulas – a primary mechanism by which states distribute funding to and among institutions of higher education (IHEs) — are a critical piece of the overall funding picture for colleges and universities, with state and local funds augmented by other sources like tuition and federal funding. For example, to better align their funding formulas with state goals and priorities, states have adjusted formulas by incorporating new student weights and adopting outcomes-based approaches. But, how do those changes come about? And what do these policies look like as they are implemented?

Dollars and Degrees: Perspectives From the Field is an ongoing series of discussions with leaders from states where higher education finance policy reform recently occurred or is happening now to answer these questions and more. By talking with leaders involved in reform efforts, advocates and policymakers elsewhere can learn promising practices from the challenges and successes their states faced.

Spotlight on Oregon

In 2013, Oregon established the Higher Education Coordinating Commission (HECC), a 15-member volunteer board appointed by the governor that advises the State Legislature, governor, and key education leaders on higher education policy. Within four years of its creation, the HECC worked alongside the State Legislature to transition the funding formula for Oregon’s four-year universities from one solely based on enrollment to one that directs money to IHEs based on student characteristics and outcomes.

Following the success of the HECC-led four-year funding formula transition, in 2022, it formed a working group to review Oregon’s funding formula for two-year colleges — a formula that had not been changed for decades. After an 18-month review process, the working group proposed a new funding formula that accounts for priority populations and incorporates new outcomes-based components for two-year colleges; these recommendations will be implemented beginning in fall 2025.

Jim Pinkard, the director of postsecondary finance and capital at the HECC led Oregon through its formula review and development of a new, more equitable design. I recently connected with him to talk about the roles of stakeholder groups in Oregon’s reform, outcomes-based funding in the new formula, anticipated challenges around implementation, and lessons learned along the way. This discussion has been edited for clarity and content.

Christine Dickason: Who were the major champions of higher education funding reform in Oregon?

Jim Pinkard: In 2021, Duncan Wyse, who was one of the HECC commissioners at the time, helped create a groundswell of support among commissioners. We weren’t lucky enough to have a piece of legislation that we could stand on, which is different from how this has unfolded in places like Texas, where the legislature initiated the higher education funding formula reform process. In Oregon, it was really a commission-led process, so the work of the HECC was instrumental.

CD: Which stakeholder groups and agencies in your state were involved in designing the new formula? Which groups were supportive — and which were more resistant to change?

JP: The working group was large, involving about 25-30 people. It had a lot of representation from the IHEs themselves, but also members of the unions (e.g., Oregon Education Association, AFT-Oregon). We also engaged with HCM Strategists, who came in as a third party to help the HECC with facilitation.

The Oregon Education Association was a hard no from Day One, and they had three seats at the table, all of whom were current faculty. AFT-Oregon had three representatives who were agnostic: two faculty and one classified staff. I think they saw the value behind an outcomes-based approach, but they weren’t too enthusiastic about it.

Most of the support for the reforms ended up coming from the colleges themselves. As we went through the process, I think we were able to demonstrate that we took their concerns seriously and were willing to compromise. The colleges persuaded the group that we should broadly define credential completion and include progression as an indicator of student success. They also convinced us that we should limit the outcomes-based metrics to no more than 10% of the total funding.

CD: Oregon’s new formula introduces outcomes-based funding for the first time to Oregon’s two-year community colleges. What’s the role of outcomes-based funding in the new formula?

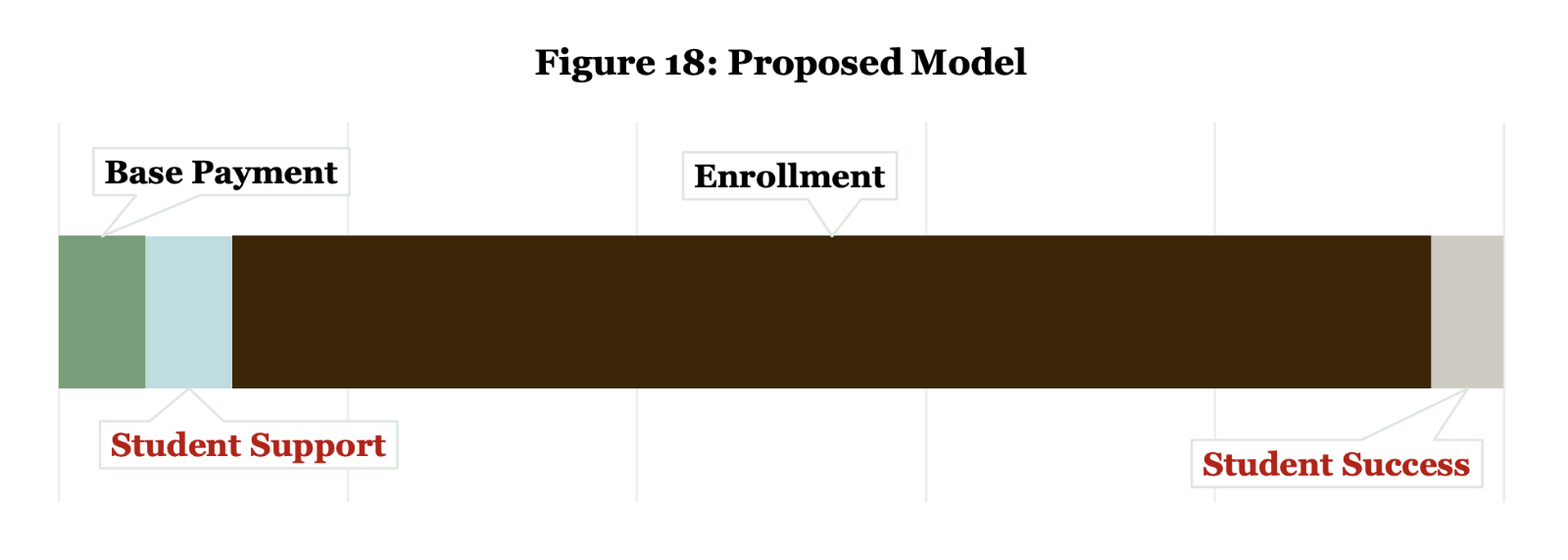

JP: As I mentioned, 10% of the redesigned funding distribution formula focuses on outcomes. We’re dividing up those dollars in two ways: 1) in support of student success on the front end (5%), and 2) in a traditional outcomes-based approach in recognition of student success, including measures of both progression and completion, on the back end (5%).

Additional weight will be given to college-enrolling students in four priority populations: 1) low income (defined as Pell Grant recipients); 2) adults ages 25 or older; 3) students taking career and technical education courses; and 4) students who belong to a racially underrepresented group (e.g., Black and Hispanic, among others). These funds will provide the money for the colleges to create the infrastructure and the wraparound services they need to support students through to completion (Figure).

Source: Community College Funding Model Review and Recommendations, HECC, 2023.

CD: Many states pay IHEs for achieving certain student outcomes only on the back end – but this new funding formula in Oregon invests in the front end through the student support component. How was that decision reached?

JP: One of the workgroup members said, “If we create all these wraparound services to improve outcomes, that costs money up front. Who’s going to pay for that? How do we do that? How do we create that infrastructure on the front end before it starts working three, four, or five years later?”

We thought those were fair questions. One of the other working group members said, “What if we did student support on the front end and student success on the back end?” And that’s the spark that started that conversation around the design of bookending. I think seeing the formula laid out visually really helped a lot of people not only see this new approach, but also get more comfortable with this proposal.

CD: Implementation of the new funding formula begins in fall 2024. What challenges do you anticipate, if any, as Oregon moves from policy design to implementation?

JP: I want to say there won’t be challenges, but I don’t know what I don’t know. I fully suspect that there will be some voices who will continue to advocate for putting a stop to this.

When our commission was asked to adopt these proposed recommendations, one of the critiques we heard was around the implementation. The IHEs asked, “Are you going to implement this immediately this fall? Because that doesn’t give us enough time to really think through the implications of it. If you delayed it by one year, that would give us time to get a fresh set of actual data and then we can start having conversations with our campus partners, including ‘if this delivers more money to our campus, what do we do with that money? How do we invest it on an ongoing basis to create the infrastructure we need to get even more money in the future? Or, what are the wider implications if this means we get fewer dollars?’”

That year-long delay was granted by the HECC. Last fall, we collected more data, and we shared those data with the IHEs. So, we’ve done a lot of prep work to get to this point, and we feel like we’re in a good place. We have continuously asked for feedback, and I haven’t heard of a lot of problems. That’s why the optimistic side of me really wants to say, “Yes, I think it’ll be a smooth implementation this fall.”

CD: What have you and others in Oregon learned through this process that other states can learn from?

JP: I don’t think we did as good a job as we could have throughout the process with messaging. We asked a third party to facilitate the meetings because the colleges and other working group members have a different cultural approach than we do. But, we didn’t focus as much on those cultural elements throughout the process initially as we should have and that’s a lesson for other states to heed.

Regarding best practices, in Oregon, it was good for us to outline a set of principles that would inform the entire review process from the very beginning. The formula has to align with our state’s higher education goals. It has to be simple, as simple as we can make it, while balancing the need for complexity. For a robust model, it has to be based on currently available data. We don’t want to create a whole new data reporting regime. It has to be aligned with our equity lens. In our state, we have the “HECC Equity Lens,” which is an expression of what equity means to us and how we pursue it and measure it. Laying these principles out in the beginning helped facilitate the process.

For more from Bellwether on higher education finance, check out the Dollars and Degrees series that offers a crash course in the essentials of higher education finance for policymakers, advocates, and others interested in improving postsecondary funding.