Fifty years ago, a group of Native educators and activists organized the first national conference on Indian education in Minneapolis, MN. Over 900 parents, community leaders, and educators came together to exchange information, share their experiences, and discuss efforts to change federal education policy. That group became the National Indian Education Association (NIEA).

Diana Cournoyer, Executive Director, National Indian Education Association

Today, NIEA is a powerhouse, not only when it comes to education for Native children, but also their civil rights efforts to change education outcomes for all students. We spoke with Executive Director Diana Cournoyer to learn more about the organization’s founding, the importance of partnering with allies, and how NIEA’s resources can be useful to educators working with students from marginalized communities.

NIEA is a client of Bellwether. The conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

NIEA just turned fifty. What were some of the social and cultural forces that led to NIEA’s founding?

Diana Cournoyer: The founding of NIEA in 1969 was initially driven by a need for education advocacy at a federal level. There had been several federally commissioned reports, like the Miriam Report in 1928 and the Kennedy Report in 1969. Again and again, these reports indicated that conditions in government funded boarding schools and public schools were harmful for Native students, but the government failed to act on that knowledge. This was also a time during which a large portion of Native populations were moving to cities to find work, and it was clear that urban public schools were dismissing the needs of Native students.

In response to an educational system lacking cultural relevance, Native language, or community inclusion, Indian education advocates held an American Indian Scholars Convocation. In 1969, these educators discussed concerns, shared best practices, and learned what was important to Indian people in the United States. Many convocation attendees desired an opportunity to continue the discourse and share ways to improve the education of Indian children.

Founding members, educators, and tribal leadership stressed the need to create an opportunity for professionals in Indian communities to discuss common interests, talk about the education of Indian students, and explore ways to be more effective teachers, better school administrators, and discover practical experiences that might provide a path for improving schools serving Indian students.

With the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015, NIEA shifted some of its focus from federal-level work to state-based work. Can you tell us more about that?

Diana: NIEA’s founders cultivated allies at the federal level, but because of the transition to state oversight of education, we’ve been increasingly focused on cultivating relationships with state education agencies. Part of the reason for this is so that we can ensure that ESSA is implemented in the manner that it was written. It’s NIEA’s mission to hold states accountable to the promises they’ve made to Native students.

Native nations are sovereign nations, and the federal government’s relationship with tribes is not unlike an international relationship. But the U.S. government has repeatedly failed to honor its responsibility to consult with tribes about a host of policies and legislation. Under ESSA, state governments must meaningfully consult with tribal nations in ways that recognize and honor their sovereignty.

Even if ESSA means more infrastructure for tribal consultation at the state level, implementation is very inconsistent from state to state. In an ideal world, state education agencies would visit Native communities to work in genuine collaboration with educators and parents and have conversations about assets, needs, and how to implement the law together.

There aren’t a lot of good examples of that happening, but at NIEA, we’re working in several states to empower advocates and tribes so that they can, in turn, ensure the state honors their sovereign rights.

Why are allies important to NIEA? What resources can help allies understand the cultural assets, strengths, and resilience of Native youth?

A large portion of Native students are taught by non-Native educators. Because of this, non-Native educators are naturally positioned to be allies to Native students, and we rely on those educators to understand their responsibility to promote culturally competent and supportive education.

Our organizational partners and allies include groups that are invested in civil rights and improving life outcomes for underserved students. And NIEA’s values include reciprocity: we understand that we can teach and share our organizational knowledge with non-Native organizations, and also that we can learn things from them. We know we need to work together to reach the future we want both for Native youth — and for all young people.

To achieve that mission, it’s important that our allies understand the history and current context of Native education. At NIEA, we wrote what we call “Native Education 101,” a primer about the history of our people in the American education system, from first contact to modern education law. There is also a great “Indigenous Ally Toolkit” from the Montreal Urban Aboriginal Community Strategy Network. While it focuses on Canadian communities and isn’t specific to education, there is so much that allies in the U.S. can learn from this resource about what it means to be a positive participant in a collective struggle for equity.

And it seems like your annual convention, which we just had the pleasure of attending, is a resource in itself, right?

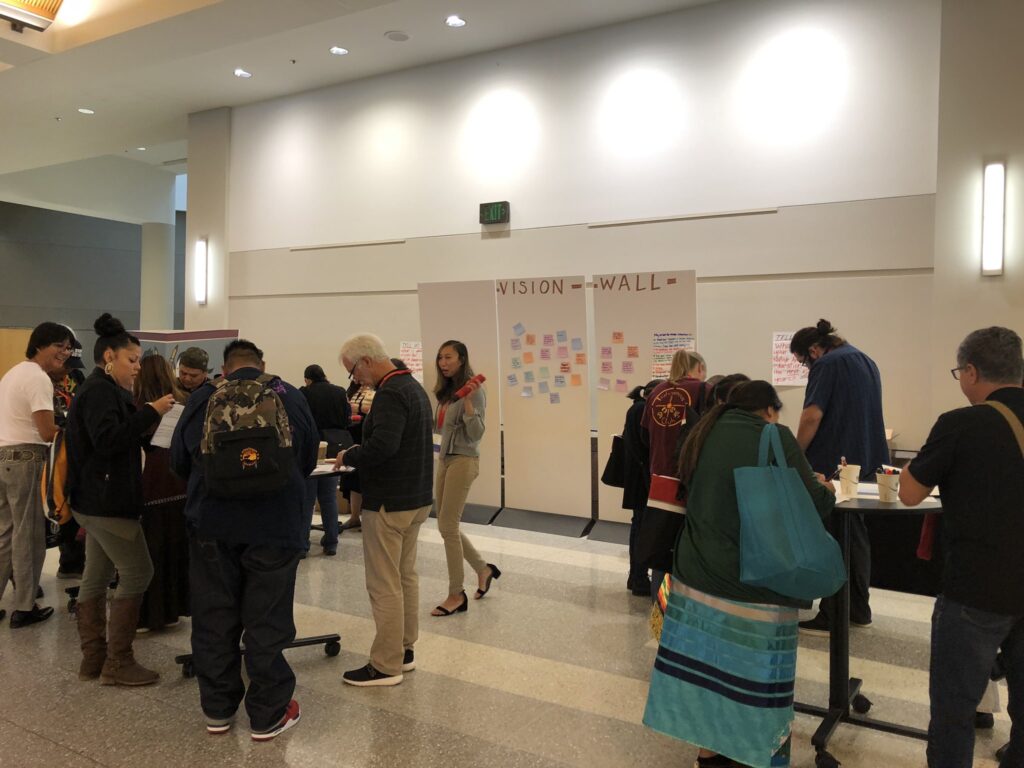

Attendees at NIEA’s 50th Annual Convention share their visions for Native education. Photo courtesy of Allison Crean Davis.

Yes, it’s a hallmark of our work. We just held our fiftieth convention in October in Minneapolis, where NIEA was founded. There is an increasingly diverse group of educators and community members who attend convention, and, in fact, it was never a space intended only for Native educators. So many groups play a role in the education of Native students. If your work or life touches that of a Native student — whether you’re a janitor, a bus driver, or a community liaison — you are very welcome at convention.

The convention is a space of laughter, engagement, and conversation. Anyone who attends will see a lot of pride in how Native people educate Native students, both individually and systemically. There is a real sense of community, relationship, and trust. It’s not forced or transactional in the way I think some other education conferences can be. At the NIEA convention, we’re fostering a space that prioritizes genuine connection.

More specifically, in the convention sessions, attendees learn about things like how Native cultural values can actually be implemented and benefit all students academically, socially, and emotionally. They learn how academic standards can be reimagined to honor Native culture and language. They learn about Native history, and the hopes and dreams that Native parents, community members, and elders have for our youth.

As you look to the next fifty years, what do you see on the horizon for NIEA?

Diana: I want NIEA to be the go-to resource when it comes to Native education. We understand how Native students — urban, rural, or on reservations — learn best. We understand that so many communities in this country, not just Native communities, are weighed down by government-induced trauma. Many Native communities are fortunate because they’ve fought to keep their culture intact. Culture is a unique and important gift. It’s not about feathers and beads. It’s about protection from the negative effects of trauma that echo through generations and impact students at school every day.

As Native people, we have something to offer the broader education community when it comes to how to deal with trauma and how to persevere.

For so long, Native communities have been overlooked by and disconnected from education systems. In many places, Native communities have been focused on survival. Going forward, NIEA will be assertive and confident in our work to ensure that Native students and Native communities thrive. It is through our culture, language, and the strength of our identity as Indigenous people that we’ve survived. It will be through those same things — the defining elements of our resilience — that Native students will thrive.

Culture-based education and trauma-informed learning models are important to NIEA. How are the organization’s approaches to these practices useful to educators working not only with Native students, but with other groups students from marginalized communities?

It seems like such an obvious thing to say, but Native people are the sole experts on our experiences, our history, and our identities. And that’s true for all ethnicities and cultural groups.

As Native people, we value sovereignty above almost anything else. We have inherent rights to govern ourselves, reject assimilation, and retain the cultures and languages that define us. Some of NIEA’s tribal capacity-building efforts, like advocacy training and community asset mapping, are good examples of work that we can do with all marginalized communities.

Culture-based education, trauma-informed practices, and social-emotional learning are cornerstones of Indigenous education, but those things aren’t unique to Native students. We know that these practices can support all students’ learning experiences. The achievement gap and the opportunity gap affect lots of communities of students, many of whom have experienced trauma. When you think about the way the history of slavery continues to reverberate in this country, when you think about some of the things happening at our country’s southern border, you see that trauma doesn’t discriminate.

For Native students, embracing cultural identity is key to healing and academic and social success. But the traditional public education system doesn’t naturally orient toward or attend to individual identities rooted in non-dominant culture. And so, at the organizing level, NIEA is pushing to shift those mindsets, approaches, and practices to acknowledge the effects of trauma and systematic oppression, but also to acknowledge cultural identity and assets. At NIEA, we have the unique ability to lead that kind of change in the field, and to shift education practice in a way that benefits all students. That’s what we’ll be doing for the next 50 years.

To read more of Bellwether’s work on Native education, click here and here.