Nearly every district in the country uses the term “alternative” to describe a broad swath of schools, including those that serve students who are pregnant and parenting, students who are new arrivals to the United States, adult learners, youth in foster care, students experiencing homelessness, or students who have previously dropped out. In short, it’s a way to classify schools that serve students who have needs that are not met or addressed by typical K-12 learning environments.

These and many other “alternative” schools meet student needs that are not going away. In the wake of COVID-19, in fact, these needs are more acute than ever. But because these schools are poorly understood by many sector leaders, their distinct strengths are at risk of going unnoticed and untapped. Rather than remaining the quirky outliers, these schools should become models for modern ways of learning, especially when flexible, hybrid, part-time, and distance learning programs are more relevant than ever.

The reality is that within the big bucket of “alternative schools,” programs differ widely: some may be quasi-virtual or residential programs while others offer evening classes or deliver two-generation support for parents and young children. Ultimately, the big label of “alternative” obscures more than it illuminates. I would like to offer a more sophisticated definition and challenge the idea that these schools are fungible alternatives to conventional education opportunities.

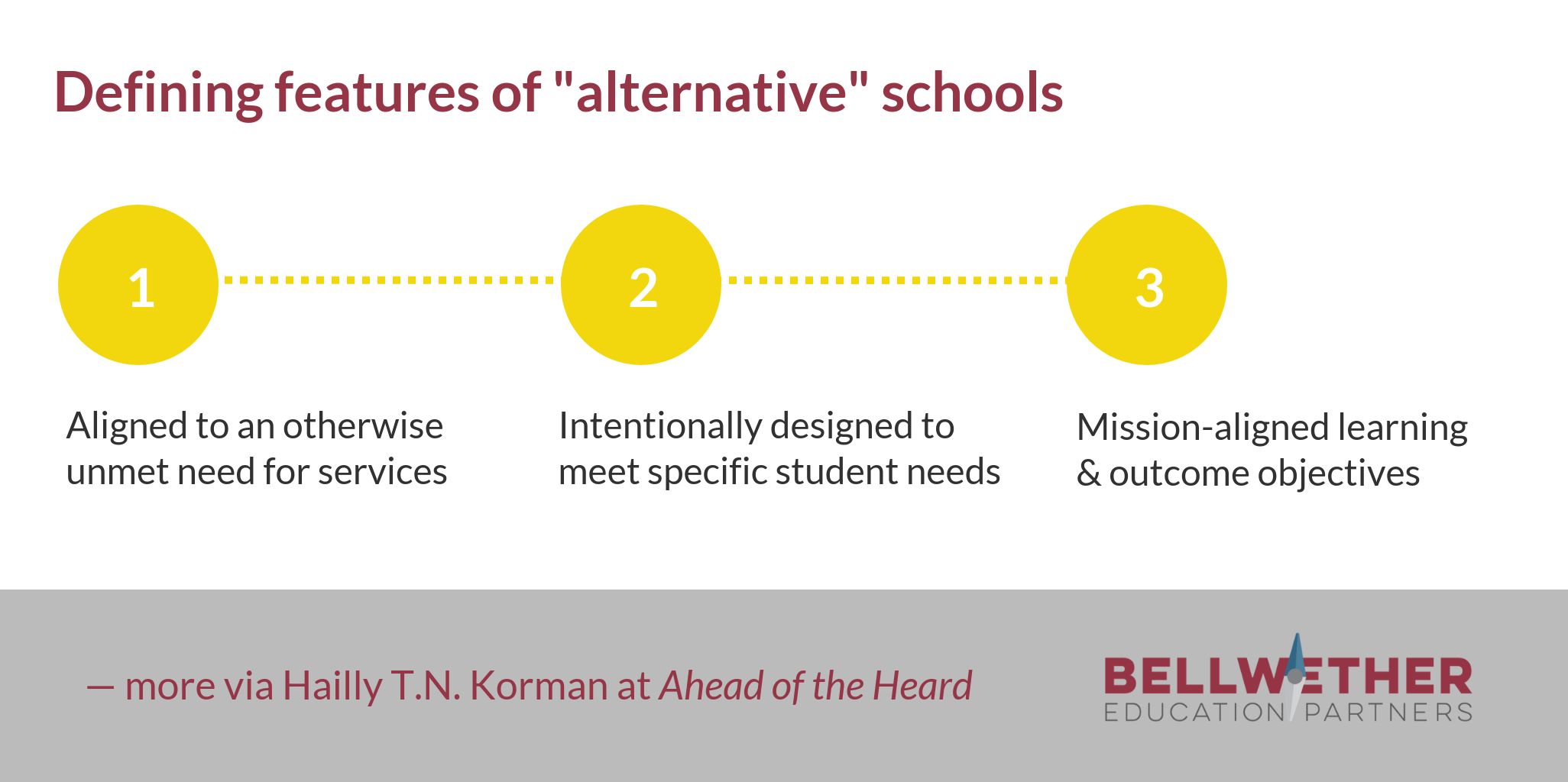

I have identified three defining features of alternative schools based on my research and experience, including many visits to schools across the country:

- They align to an otherwise unmet need for services. For the most part, the alternative to many of these schools is not attending school at all.

- They are intentionally designed to meet a set of specific student needs. This may be a complex constellation of needs, but the designers of the school’s programs and services are guided by the needs, wants, and constraints of the young people that they serve. As a result, they may look much different operationally from a traditional school.

- They set mission-aligned learning and outcome objectives (e.g., improved parenting skills, increased school attendance, or developmental milestones of social and emotional learning) and may adjust the thresholds or timelines for traditional metrics of school success (for example, using a six-year graduation rate rather than a four-year measurement).

I believe that schools meeting all these criteria can safely be called “alternative,” but even within that category, I’ve discovered further useful distinctions. Below I offer an overview of three common types of programs, each with its own real-world illustration.

Schools that offer intensive in-person services

Although many charter models tout their unique in-person school culture and the intangible learning experiences that they create in their buildings, few programs offer the kind of in-person service delivery that a school like Monument Academy, a five-day-a-week boarding school in Washington DC, delivers. With a weekday boarding program for nearly 100 youth, many of whom are in formal foster care or informal kinship care, the physical aspect of the program model is foundational.

Youth in foster care often have unique needs that typical public schools are not always prepared to meet (as my colleague Justin Trinidad and I explore in a paper released last month). For example, they may have moved schools frequently and carry partial credits on their transcripts. They may need counseling and transportation services. Youth in foster care are also more likely than their peers to have special education needs, both because children with special needs are more likely to experience maltreatment and because some kinds of maltreatment can cause (or exacerbate) disabilities. With these realities in mind, Monument offers in-person supportive services like counseling, connections to clinicians, social activities, and extracurricular engagement around-the-clock.

Monument’s model assumes that relationships lay the foundation for all other programming, and indeed many school leaders over the last few months have reflected on how the strength (or weakness) of their relationships with students affected their ability to keep them engaged in continuous learning. Whether schools like these are able to weather the crisis of COVID-19 and constraints on congregating remains to be seen, but that does not diminish the value of these types of programs into the future.

Schools that target interrelated complex needs

Some alternative school models are designed with a specific set of student needs in mind. These needs are often contemplated in isolation by more traditional school models but rarely addressed holistically. New Legacy, a school in Aurora, Colorado, meets a particular set of concurrent needs by serving parenting youth in a school of their own with an on-site early learning program.

New Legacy’s two-generation strategy is an object lesson in the problems that most cities are grappling with today: how to offer appropriate schooling for student parents, high-quality early learning opportunities, and affordable daily child care. New Legacy has developed one holistic solution to what has historically been contemplated as several related, but siloed, problems. But New Legacy’s model faces a crucial challenge: it is not necessary to operate just an early learning center if parents are not attending school, and it does not make sense to operate just a school when parents will still need child care.

COVID-19’s school closures and the fallout for child nutrition programs, mental health services, wellness programs, and other “non-academic” roles that schools play are a compelling demonstration that schools like New Legacy, where constellations of needs are addressed comprehensively as part of the school’s design. Schools like New Legacy are likely to be an essential component of a healthy local education ecosystem in the future.

Schools that are designed to offer maximum flexibility

A number of alternative schools are defined by their flexibility around the physical space for learning (remote or classroom), the delivery of instruction (asynchronous or live instruction), and the modality (online or in-person). Learn4Life, a network of charter schools in California (as well as other states), demonstrates agility across all three — as I’ve explored in a new op-ed, out today with CalMatters:

Take Learn4Life, a charter school with campuses in California, which offers a hybrid, part-time model. Flexibility is what makes it an option for the 20,000 students it serves. The program provides credit recovery for students coming back to school and different pathways to graduation, including flexible scheduling for students who work or provide for their family.

Learn4Life’s flexibility includes completing coursework at home or attending physical sites with qualified teachers, tutors and counselors. Students who attend in-person usually attend two or three days per week and complete additional coursework independently. When in-person, the program offers mentoring, counseling and support for parenting students.

And like most alternative schools, the focus is on achieving mastery and less on progressing through each school day until graduation. The needs of students dictate that educators think about what learning is and how to adapt.

When COVID-19 caused learning to be exclusively at home, Learn4Life quickly adapted to an all-digital model, providing laptops and hotspots and delivering uninterrupted learning for the very students who were most likely to have previously experienced disruptions.

Learn4Life’s model did not only quickly become the remote learning standard, but it will likely meet a significant need in the coming school year. This mindset toward flexibility and adaptability quickly became an essential asset rather than just an idiosyncratic choice of school design.

Sector leaders should consider the distinct value alternative schools provide to students, families, and communities.