Over the coming months, high school seniors across the country will anxiously wait to hear which colleges have accepted them. And after all the hard work of applying comes another tough step: deciding where to go to college.

How do young people decide where to go to college? Do they pick the most selective school, or do they prioritize the place where their friends are going? Do they stay close to home or get as far away as possible? Big school or small school? Urban or suburban? Public or private? Greek life or geek life?

There are countless factors to weigh, which can make the college selection process feel overwhelming, particularly for students from low-income backgrounds and those who are the first in their family to attend college. As counselors, advisers, and mentors to young people, we need to build systems and processes that enable them to make informed postsecondary choices.

Fortunately there’s a useful framework for considering postsecondary options that’s gaining popularity among high school counselors and frontline staff in college access programs: “match and fit.”

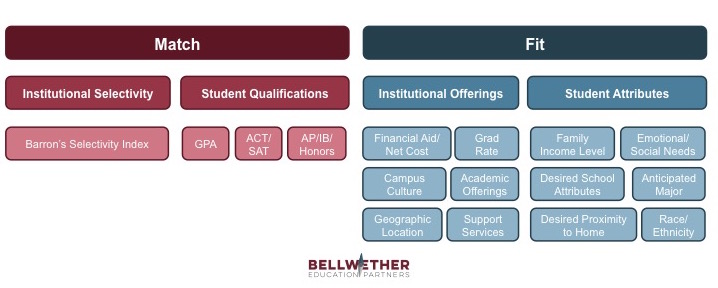

While there is no standard definition, practitioners generally agree on the following working definitions:

- Match: The degree to which a student’s academic credentials align with the selectivity of the college or university in which they enroll. Match encompasses the quantitative elements of choosing a postsecondary option; it is more science than art.

- Fit: A more nebulous concept that refers to how well a prospective student might mesh with an institution once on campus: socially, emotionally, financially, and otherwise. Fit encompasses the qualitative elements of choosing a postsecondary option; it is more art than science.

Together, these concepts enable students, families, and college counselors to share a common language when talking about college. A student may technically “match” to a particular institution based on their academic credentials, but then decide that school is not a great “fit” given their desires and interests. Conversely, a student might have their heart set on a college — it may seem like a perfect “fit” — but it may turn out to be a poor “match” when the student’s GPA and test scores are considered.

Importantly, these concepts can be used to support equity in access for underserved students. Here’s how:

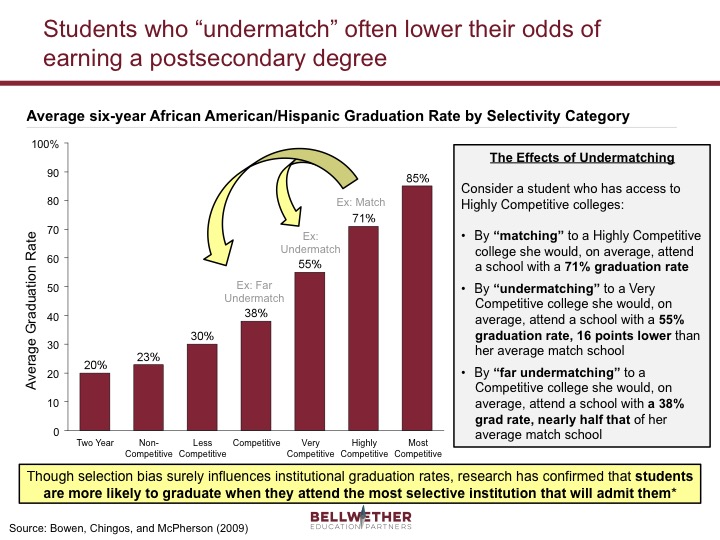

Research shows that students from low-income families are more likely to attend less selective institutions than what their hard-earned GPA and ACT/SAT scores would otherwise allow, a phenomenon known as “undermatching.” The problem with this is that less selective institutions often have less financial aid to give, offer fewer academic and social supports for students, and see lower graduation rates. “Undermatched” students often face longer odds to complete a postsecondary degree or certificate, as illustrated below.

The good news is that undermatching can be avoided by paying attention to three steps of the college-going process:

- Application: A student undermatches because they did not apply to a match or more selective school.

- Admittance: A student undermatches because they applied but were not admitted to a match or more selective school.

- Enrollment: A student undermatches because they were admitted but chose not to attend a match or more selective school.

Over the years, our teams at Bellwether have worked with a range of college access and success organizations, from national groups like Network for College Success and National College Access Network, to place-based intermediaries like Success Boston and Achieve Atlanta, to direct service provider nonprofits like OneGoal and College Summit, to dozens of schools and school districts across the country. Through this work, we have identified strategies that address each of these root causes of undermatching:

- Focus on applications: Of the three forms of undermatching, “not applying to a match school” is the most straightforward to influence. Many schools and districts across the country are beginning to set goals around both the quantity and quality of college applications. For example, a large urban district in the Midwest has set goals around the percentage of high school seniors who submit at least three applications, the percentage who apply to at least one match or more competitive school, and the percentage who are admitted into at least one match or more competitive school.

- Start early: Building a college-going culture starts in 9th grade or before; use “match and fit” language early and often. Push for strong college lists by the end of junior year to tee up a targeted application process in the fall of senior year. We’ve seen several charter school networks implement college access programming during homeroom or advisory periods so that their students begin exploring postsecondary options at the beginning of high school (or even earlier).

- Leverage data to build smart lists: Beginning in junior year, college advisers should support students to create data-informed college lists. Students should be able to explain how a variety of “match” (safety/target/reach) and “fit” (finances, grad rate, culture, proximity, etc.) considerations apply to the schools on their list. For example, one college access nonprofit we’ve worked with requires their students to create a list of colleges they are considering by the end of junior year. Students use a digital list-building tool to draft a list of 12 schools: seven “match” or target schools, three “overmatch” or reach schools, and two “undermatch” or safety schools. By supporting students to create data-informed lists early in the college exploration process, we can drastically increase the odds that a student will apply to and ultimately enroll in a college that is a good “match” and a strong “fit.”

Choosing a postsecondary option that is both a strong “match” and a good “fit” is more than an intellectual exercise: low-income students who attend a college that matches their qualifications are more likely to succeed.

Stay tuned for more on Bellwether’s work in post-secondary access.