In October 1970, Willie Wright, a middle school principal in Florida, used a wooden paddle to strike his 8th-grade student James Ingraham more than 20 times. Ingraham subsequently sought medical treatment for a hematoma and missed nearly two weeks of school. However, when the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed Ingraham’s treatment in 1977, it held in a 5-4 ruling that school corporal punishment does not violate the U.S. Constitution’s Eighth Amendment ban on “cruel and unusual” punishment nor the 14th Amendment’s due process clause. As a result, tens of thousands of students continue to experience corporal punishment at school each year, despite its widespread perception as an obsolete practice.

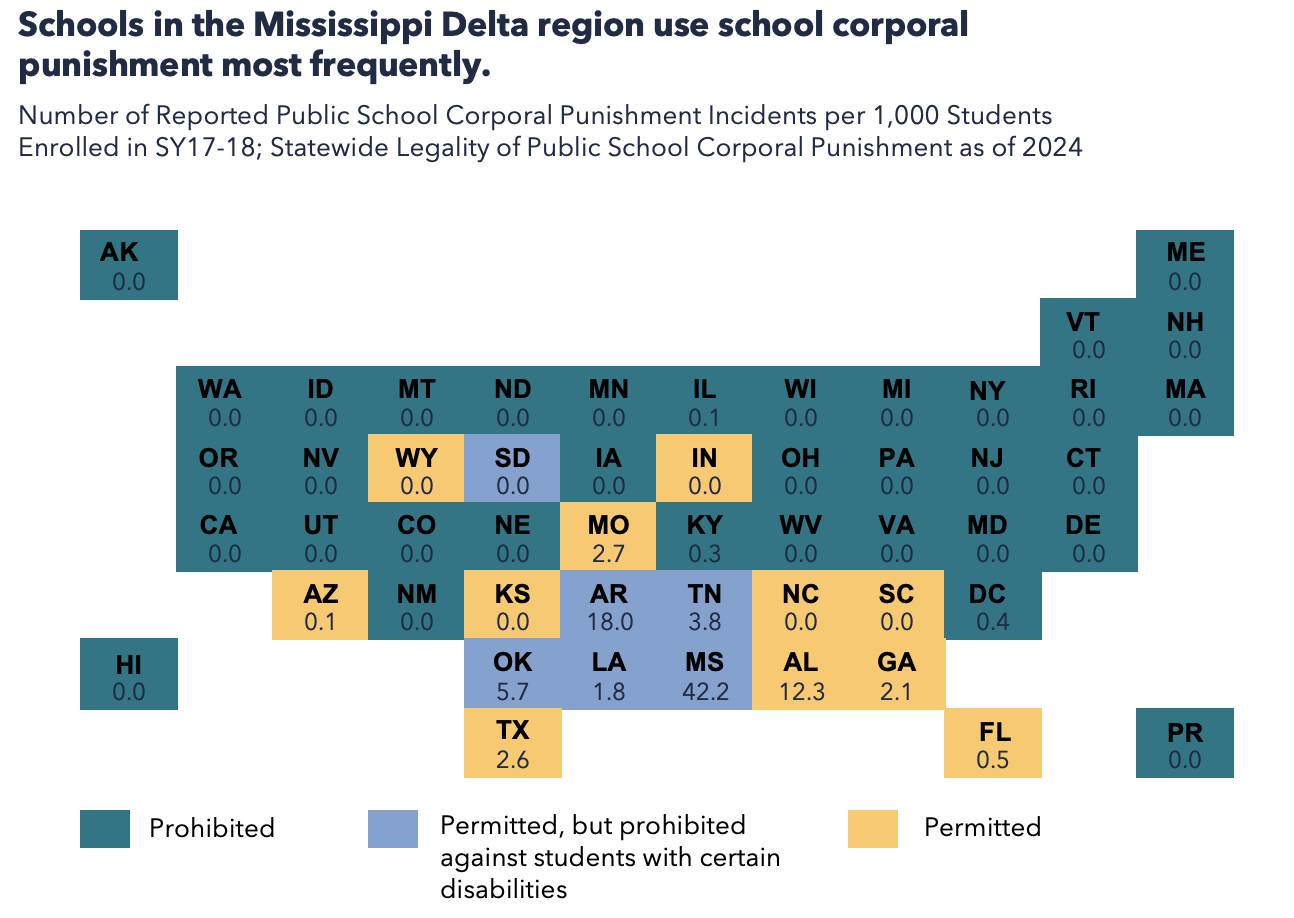

Corporal punishment is banned in schools in more than 130 countries and has long been prohibited in U.S. prisons. Yet in 2024, 17 states continue to use corporal punishment — defined by the U.S. Department of Education as “paddling, spanking, or other forms of physical punishment” — as a means of disciplining students. Within these states, school districts may voluntarily adopt policies that prohibit or restrict the practice.

During the 2017-18 school year (SY), nearly 70,000 American public school children received corporal punishment from K-12 school officials.1 Seventy thousand may be a small percentage (0.14%) of American public school students, but given the evidence pointing to corporal punishment’s negative physical, psychological, and developmental impacts and its disproportionate use against Black students, Indigenous students, and students with disabilities, the continuation of this practice in U.S. schools warrants further attention.

A Concentration in the Mississippi Delta Region

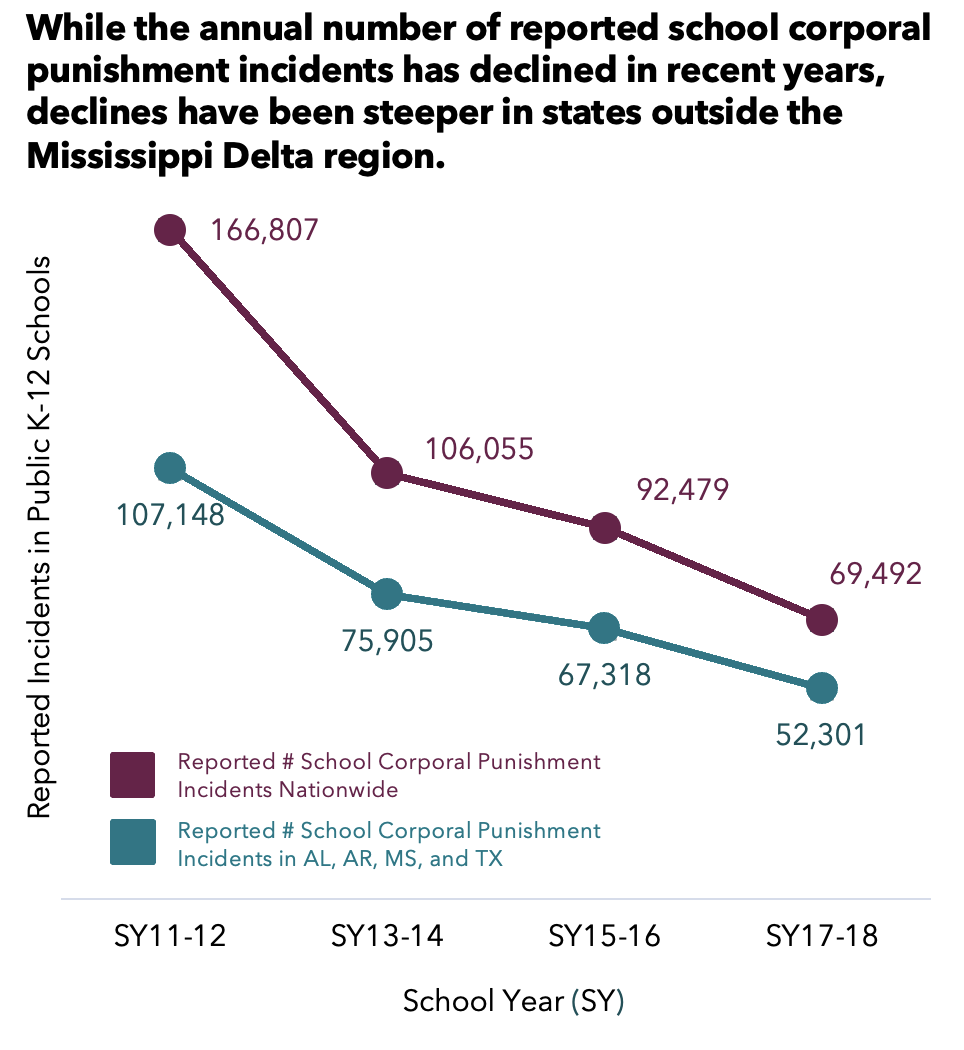

More than three-quarters of all reported school corporal punishment incidents occur in just four states: Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas (Figure 1). Reported incidents have been declining nationwide in recent years, but the number of incidents in these four states has decreased at a rate slower than in other states (Figure 2). These data highlight that states with some of the highest poverty rates in the nation — along with some of the highest concentrations of Black students in the country — apply corporal punishment most frequently. This wide variation in state laws and their application emphasizes another reality of American public education: a young person’s schooling experiences vary drastically based on where they happen to live.

Figure 1: U.S. Public School Corporal Punishment Legality (2024) and Usage (SY17-18) in 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico

Figure 2: Number of Reported School Corporal Punishment Incidents in the U.S. by School Year

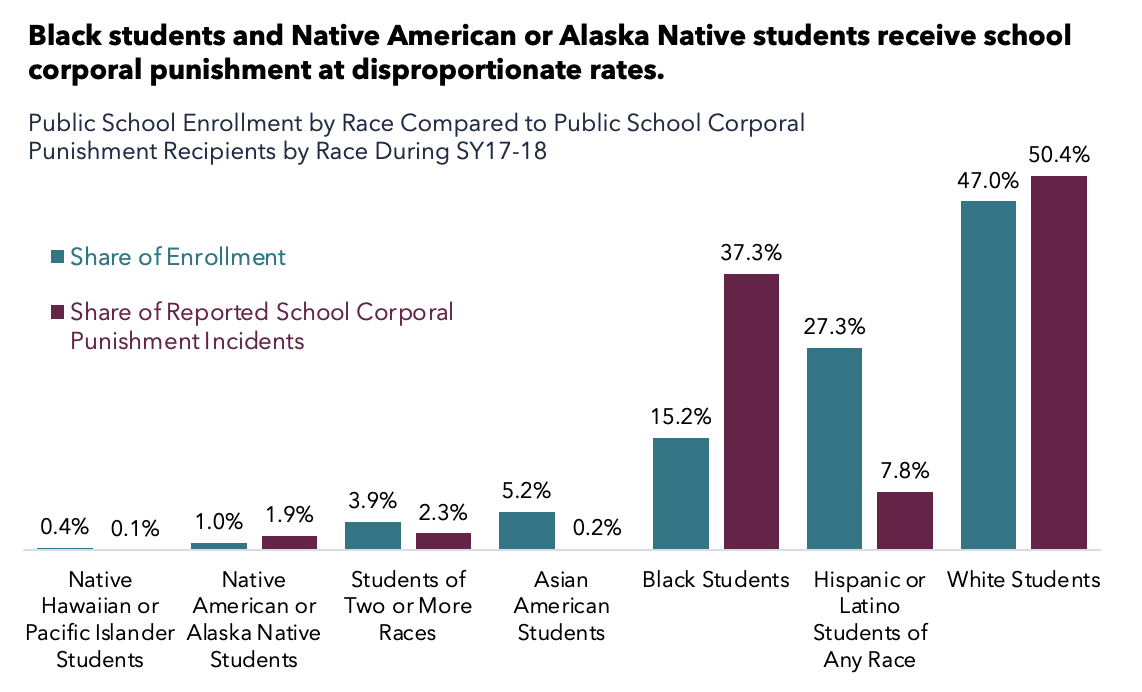

School Corporal Punishment and Systemically Marginalized Students

Like other strict approaches to school discipline, corporal punishment disproportionately affects Black students, Native American or Alaska Native students, and students with disabilities. For example, although Black students constituted 15.2% of public school students during SY17-18, they represented 37.2% of all corporal punishment recipients (Figure 3). During the same period, Native American or Alaska Native students were nearly twice as likely as white students to receive corporal punishment at school. Likewise, students defined as having disabilities under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or Section 504 comprised 15.8% of national public student enrollment in SY17-18, yet 19.2% of all corporal punishment recipients.

To combat these inequalities, six of the 17 states that allow corporal punishment (Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Tennessee) prohibit school officials from inflicting it upon students with certain disabilities.

Figure 3: Racial Disparities in School Corporal Punishment Application in the U.S.

Negative Associations with Student Learning

Although proponents of school corporal punishment contend that it reduces classroom disruptions, research has consistently demonstrated that receiving it is negatively associated with a student’s behavioral, cognitive, and emotional development. Furthermore, receiving school corporal punishment as an adolescent is correlated with a lower high school GPA and higher depressive symptoms years later. Recently, these findings prompted the U.S. Department of Education and American Academy of Pediatrics to call for the abolition of corporal punishment in school settings.

Although corporal punishment is linked to worsened outcomes for those who receive it, research has yet to discern how it affects the behavior and attainment of all students within a school — an area that demands further investigation.

Strides to End the Practice

Nearly 50 years after the Supreme Court’s decision in Ingraham v. Wright, children’s advocates across the country, such as the U.S. Alliance to End the Hitting of Children, are continuing the movement to end corporal punishment in schools. In Congress, Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) introduced the Protecting Our Students in Schools Act of 2023, which would ban corporal punishment in federally funded schools. At the state level, bipartisan coalitions of legislators in Colorado and Idaho banned school corporal punishment in 2023, while elected officials in Oklahoma and Tennessee introduced legislation to limit the use of the practice in 2024. Despite facing setbacks at the state and national level, these advocates have continued to mobilize in pursuit of corporal punishment prohibitions.

Given that corporal punishment is linked to worsened student behavior, mental and physical health, and cognitive performance, efforts to abolish school corporal punishment must continue, as the data show that many schools will keep using corporal punishment as long as it’s allowed. Finally abolishing the practice nationwide would bring us closer to creating safe, trusting learning environments for all K-12 students.

To learn more about corporal punishment in public schools, see our data visualization source list.

1The authors rely on national data from the SY17-18 U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) survey, as the SY20-21 CRDC survey was heavily impacted by COVID-19 pandemic school closures; data from the SY21-22 CRDC survey will be released by the U.S. Department of Education in 2025.