Journalists, as a general rule, use accessible language. Researchers, as a general rule, do not. So journalists who write about academic research and scholarship, like the reporters at Chalkbeat who cover school spending studies, can help disseminate research to education leaders since they write more plainly.

But the danger is that it’s easy for research to get lost in translation. Researchers may use language that appears to imply some practice or policy causes an outcome. Journalists can be misled when terms like “effect size” are used to describe the strength of the association even though they are not always causal effects.

To help journalists make sense of research findings, the Education Writers Association recently put together several excellent resources for journalists exploring education research, including 12 questions to ask about studies. For journalists (as well as practitioners) reading studies that imply that some program or policy causes the outcomes described, I would add one important consideration (a variation on question 3 from this post): if a study compares two groups, how were people assigned to the groups? This question gets at the heart of what makes it possible to say whether a program or policy caused the outcomes examined, as opposed to simply being correlated with those outcomes.

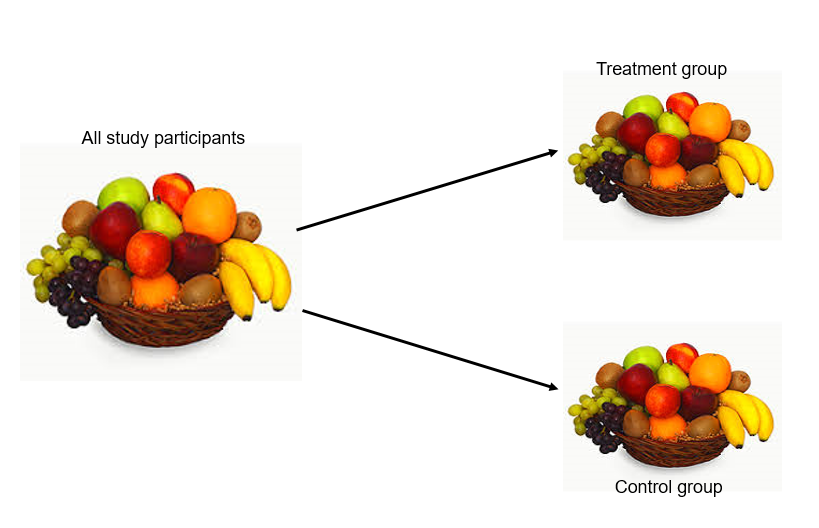

Randomly assigning people creates a strong research design for examining whether a policy or program causes certain outcomes. Random assignment minimizes pre-existing differences among the groups, so that differences in the outcomes can be attributed to the treatment (program or policy) instead of different characteristics of the people in the groups. In the image below, random assignment results in having similar-looking treatment and control groups.

In the absence of random assignment, the groups might look different. If the groups have different characteristics, we won’t know if the outcomes are due to the program/policy being studied, or to the different characteristics of people in one group versus another.

One example of this in the world of education research comes from a recent Inside Higher Ed summary of research on college campus housing. The research compared the grade point averages (GPA) of students living in apartment-style housing to those living in corridor-style (e.g., dorm) housing. On Twitter, some researchers denounced the study’s methods, saying it was a case of correlation not causation. In other words, it may be the case that students living in apartment-style housing do worse in school, but that doesn’t mean that living in apartment-style housing made them do worse.

This particular study analyzed data from students who self-selected their housing type. It’s possible that the type of student who self-selected apartment-style housing is also the type of student who, for any number of reasons, has lower grades in the first semester of college. For example, they may be less likely to join study groups, attend office hours, or engage in other social interactions that might support a higher GPA.

The researchers were careful to say: “We found that socializing architecture was positively associated with a higher first-semester grade point average.” Use of the word association is a signal that the authors are not claiming a causal relationship between architecture and GPA, meaning where you live doesn’t determine your academic success.

But the researchers also used terminology that could have made a layperson think that apartment housing caused poor grades. The subtitle is “The Influence of Residence Hall Design on Academic Outcomes”; influence is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the power or capacity of causing an effect in indirect or intangible ways.” And the first sentence of the abstract says, “This study investigates the impact of residence hall architecture on students’ academic achievement.” Inside Higher Ed repeated that language without critiquing it.

Many studies, both qualitative and quantitative, provide rich, descriptive information about policies and practices and how those are related to outcomes, but they do not have a methodology that supports causal inference. That is, they don’t provide evidence that policies and practices cause the outcomes they examine. This doesn’t mean that those studies shouldn’t be covered by reporters or that they don’t make a worthwhile contribution. In the case of the campus housing study, we might use these findings to encourage colleges to consider using a method of assignment that would enable stronger research designs in future studies, so we can build on what we’ve learned from this observational study. However, it should be interpreted as descriptive study, not a causal one.

Journalists play a crucial role in translating research for policymakers and practitioners. They also ask tough questions that can shed light on whether research findings are on solid ground, or are being oversold. High-quality journalism on education research can increase the chances that all students benefit from evidence-informed policies and practices, so all the more reason to make sure we understand each other’s language.

June 27, 2019

Correlation is Not Causation and Other Boring but Important Cautions for Interpreting Education Research

By Bellwether

Share this article

More from this topic

What the Supreme Court’s Mahmoud v. Taylor Decision Means for Schools and Families

Meeting the Moment: How 4 Philanthropic Foundations Are Stepping Up Right Now

Teaching Interrupted: How Federal Cuts Threaten a Promising Teacher Residency Program

No results found.