July 12, 2018

Expand Your Ed Policy Toolkit with Human-Centered Design

By Bellwether

Share this article

In February, I released a white paper making the case that policy professionals can create better education policies by using human-centered research methods because these methods are informed by the people whose lives will be most affected.

Yesterday, we released a companion website (https://designforedpolicy.org/) that curates 54 human-centered research methods well-suited to education policy into one easy-to-navigate resource. We took methods from organizations like IDEO, Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, and Nesta and organized them by the phases of a typical education policy project. We included brief explanations of how each method might be applied to your current work.

To be sure, you probably already use some human-centered design methods in your work, even if you don’t think of them that way. Interviews and observations are commonplace and provide highly valuable information. What the design world brings is a mindset that explicitly and deeply values the lived experiences of the people who are most impacted by problems and an array of methods to capture and analyze that information. It also adds a heavy dose of creativity to the process of identifying solutions. And despite a common misconception, when done well, human-centered design methods are very rigorous, fact-based, and structured to root out assumptions and biases.

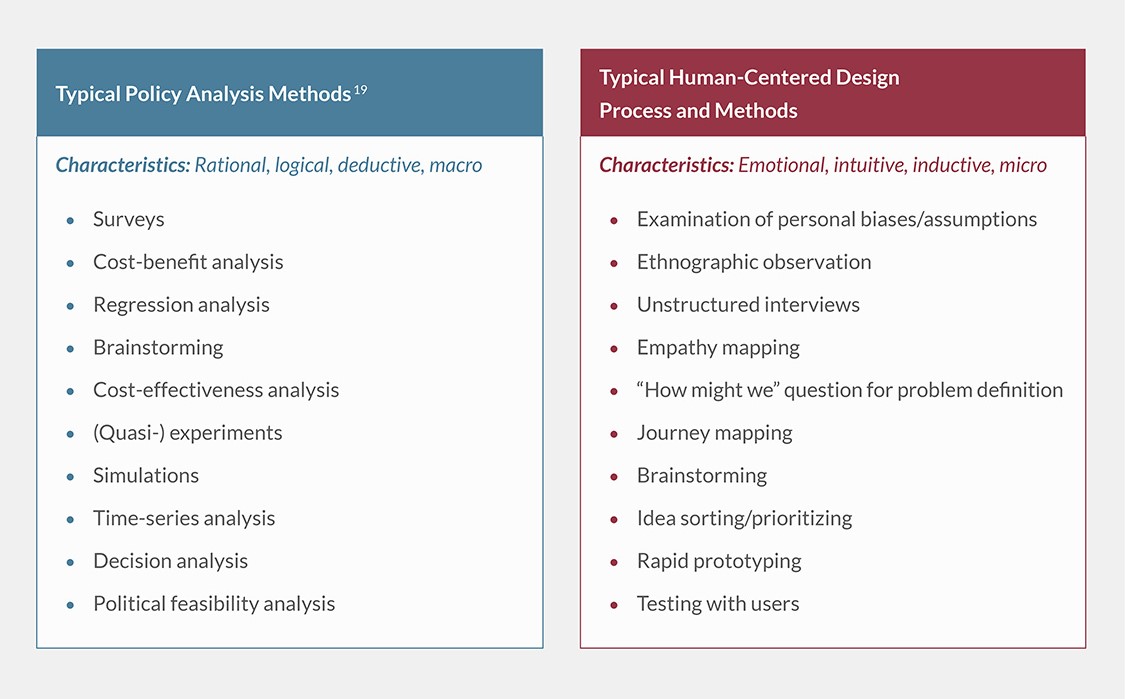

When combined, common policy analysis methods and human-centered design methods can result in a powerful mix of quantitative and qualitative, deductive and inductive, macro and micro, rational and emotional elements.

Many of my colleagues and I have used human-centered design methods and are integrating them more as we’re building expertise on the issue. For example, in a recent project seeking to understand the education experiences of students who came into contact with foster care, mental health services, and other public agencies in El Dorado County, Californa, we interviewed dozens of students in secure facilities, created a persona, and constructed a journey map to communicate what we heard to county education and civic leaders (pictured below). We then leveraged their expertise to generate and evaluate potential solutions based on impact and feasibility using 2×2 matrices.

Starting with the needs, experiences, and ideas of the students most affected by an education policy or practice kept potential solutions laser-focused on how we could improve their lives rather than settling for fixes that were simply politically feasible, logistically convenient, or satisfying for adults.

As we work with clients and funders, we’ll continue to look for opportunities to bring human-centered methods to our quantitative toolkit to articulate more accurate definitions of problems, generate a wider variety of potential solutions, and continue to meaningfully involve community members in the creation of rules and laws that affect them. We hope our new website will serve as a resource for others looking to do the same.

More from this topic

Meeting the Moment: How 4 Philanthropic Foundations Are Stepping Up Right Now

Teaching Interrupted: How Federal Cuts Threaten a Promising Teacher Residency Program

Does Increasing Graduation Requirements Improve Student Outcomes?

No results found.