Somewhere between 10 and 30 percent of all new teachers are hired after the school year begins. These late hires come in with lower college GPAs, are less likely to have prior teaching experience, and are less likely to be licensed in the area they’ll be asked to teach. Late hires tend to be concentrated in certain low-performing schools. And, since they tend to have higher turnover rates, late hires also contribute to higher churn in those schools.

TNTP began documenting these trends more than a decade ago, but the process through which teachers are hired largely remains a blind spot for education reform. Over the last few years, we’ve devoted far more attention and resources on the ways districts evaluate existing teachers and principals, while doing comparatively little to help districts improve the quality of educators coming into their schools. As part of Bellwether’s recent publication outlining 16 education policy ideas for the next president, I propose a new federal investment to help districts in transforming their hiring and on-boarding processes.

The problem is clear: District hiring processes are notoriously sluggish and bureaucratic, and schools often don’t even know how many openings they’ll have to fill in the coming school year until well into summer. This causes districts to scramble to find teachers right before the school year starts. A recent paper from John Papay and Matthew Kraft found that teachers who were hired after the school year started had a significant negative impact on student achievement. The results were equivalent to the loss of approximately two months of instruction for a typical middle school student.

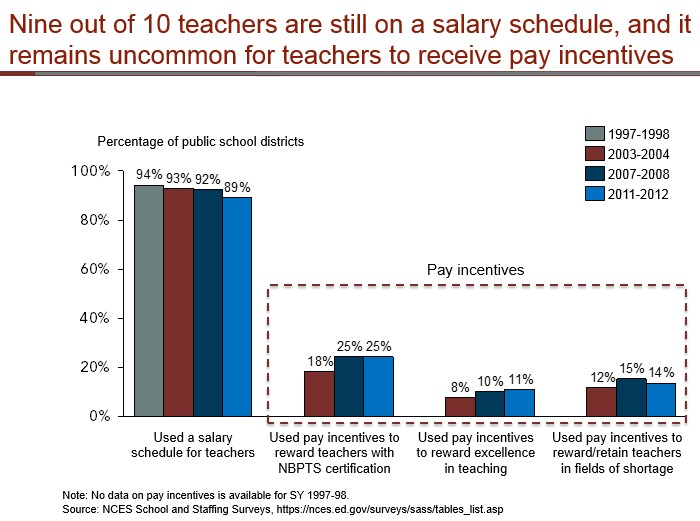

Moreover, districts tend to outsource the role of screening, training, and recruiting new hires. Many teachers are hired without even demonstrating so much as a sample lesson plan. Even after selecting candidates, schools are unlikely to offer hiring bonuses or other incentives to land their top choices. Less than one in 10 school districts offers recruiting incentives for teachers or principals, and only one in six offers extra financial compensation for educators to work in shortage areas. Despite current cries of a national “teacher shortage,” districts act like the laws of supply and demand don’t apply to teachers, and they treat teachers as if they’re immune to financial incentives.

Graphic via Bellwether’s 2014 report, Teacher Evaluations in an Era of Rapid Change

Finally, districts have much to learn about how to successfully on-board new hires. Not enough districts offer mentoring or formal induction programs, and most districts throw teachers into the fire on the first day of school and expect them to sink or swim, rather than giving them lower-stakes practice time first. (Late hires make this effectively impossible.)

Some school districts, like Boston, MA; Spokane, WA; and Washington, DC, have been able to improve their teacher hiring processes, and their efforts could be spread to the rest of the country. There’s a clear model for how the federal government could help. For the last 10 years, it has offered competitive grants for districts to revamp their teacher evaluation and compensation systems. That theory of action has proved challenging for a number of political and methodological reasons, but the investment helped spur dramatic changes across schools and states.

There has been no similar effort to improve front-end hiring practices, even though it may be a more promising approach. Revamping school district hiring practices would give districts opportunities to plan more effectively, hire earlier in the year, and get teachers in low-stakes teaching opportunities before the school year begins. All this would, in turn, lead to more effectively run school systems, a more sane hiring process for teachers, and better outcomes for kids.

For more on this topic, or other ideas in the series, please read the full 16 for 2016: 16 Education Policy Ideas for the Next President.