Everyone loves a good rivalry. The Hatfields vs. the McCoys. Aaron Burr vs. Alexander Hamilton. Taylor Swift vs. Katy Perry.

As evaluators, we’re partial to Tupac vs. Biggie. For the better part of three decades, these rappers from opposing coasts have remained in the public eye, recently reemerging with the release of a television series about their unsolved murders. Interestingly, their conflict about artistry and record labels mirrors a conflict within evaluation’s own ranks around a controversial question:

Can advocacy be evaluated?

On the East Coast, Harvard’s Julia Coffman acknowledges that evaluating advocacy can be challenging, thanks to the unique, difficult-to-measure goals that often accompany these efforts. Nevertheless, she contends, these challenges can be mitigated by the use of structured tools. By using a logic model to map activities, strategies, and outcomes, advocates can understand their efforts more deeply, make adjustments when needed, and, overall, reflect upon the advocacy process. This logic model, she claims, can then become the basis of an evaluation, and data collected on the model’s components can be used to evaluate whether the advocacy is effectively achieving its intended impact.

In contrast to the East Coast’s structured take, West Coast academics refer to advocacy as an “elusive craft.” In the Stanford Social Innovation Review, Steven Teles and Mark Schmitt note the ambiguous pace, trajectory, and impact related to the work of changing hearts and minds. Advocacy, they claim, isn’t a linear engagement, and it can’t be pinned down. Logic models, they claim, are “at best, loose guides,” and can even hold advocates back from adapting to the constantly changing landscape of their work. Instead of evaluating an organization’s success in achieving a planned course of action, Teles and Schmitt argue that advocates themselves should be evaluated on their ability to strategize and respond to fluctuating conditions.

Unsurprisingly, the “East Coast” couldn’t stand for this disrespect when the “West Coast” published their work. In the comment section of Teles and Schmitt’s article, the “East Coast” Coffman throws down that “the essay does not cite the wealth of existing work on this topic,” clearly referring to her own work. Teles and Schmitt push back, implying that existing evaluation tools are too complex and inaccessible and “somewhat limited in their acknowledgement of politics.” Them’s fighting words: the rivalry was born.

As that rivalry has festered, organizations in the education sector have been building their advocacy efforts, and their need for evidence about impact is a practical necessity, not an academic exercise. Advocacy organizations have limited resources and rely on funders interested in evidence-based results. Organizations also want data to fuel their own momentum toward achieving large-scale impact, so they need to understand which approaches work best, and why.

A case in point: In 2015, The Collaborative for Student Success, a national nonprofit committed to high standards for all students, approached Bellwether with a hunch that the teacher advocates in their Teacher Champions fellowship were making a difference, but the Collaborative lacked the data to back this up.

Teacher Champions, with support from the Collaborative, were participating in key education policy conversations playing out in their states. For example, in states with hot debates about the value of high learning standards, several Teacher Champions created “Bring Your Legislator to School” programs, inviting local and state policymakers into their classrooms and into teacher planning meetings to see how high-quality, standards-driven instruction provided for engaging learning opportunities and facilitated collaborative planning.

But neither the Collaborative nor the teachers knew exactly how to capture the impact of this work. With Teacher Champions tailoring their advocacy efforts across 17 states, the fellowship required flexible tools that could be adapted to the varied contexts and approaches. Essentially, they needed an East Coast/West Coast compromise inspired by Tupac and Biggie and anchored by Coffman, Teles, and Schmitt.

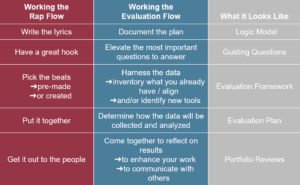

By introducing evaluation through this hip hop rivalry and referencing the views of our scholarly colleagues, we were able to employ an evaluation design that the Teacher Champions found approachable yet rigorous. We empowered them to build logic models and collect data about their impact (shoutout to the East Coast), and used rap to provide a useful, if irreverent, metaphor:

We also had to acknowledge though, that advocacy work is nonlinear, and advocates must adapt and respond to changing conditions (shoutout to the West Coast). So we left plenty of room for choice and flexibility in the evaluation process. For example, we created common survey tools with core questions for all teachers to use, but also helped Teacher Champions tailor them to their local advocacy initiatives. Because teachers’ voices often go unheard, creating opportunities for them to take control of the evaluation process was doubly important to us. Capturing activity-specific data also helped us embrace the “messiness” of advocacy evaluation instead of being paralyzed by it.

In mediating this rivalry, we created our own middle ground for evaluation that empowered teacher advocates, gave them continuous feedback on their results, and allowed us to capture consistent data for the fellowship at the national, big-picture level. Best of all, teachers enjoyed it so much that they began applying evaluation tools, like the logic model, to other work they were doing. While we’re sure we didn’t get it perfectly right, we know this approach worked and have had other advocacy organizations ask us how to structure something similar.

When rap came on the scene thirty years ago, the music industry had to carve out a space for it — to create a category for work that shifted the field in significant ways. We experienced the same sort of shift by recognizing that when it comes to advocacy, the middle ground for evaluation — structure and flexibility — was the best path forward.

One of the most powerful things about rap is that it provides marginalized people a way of documenting their experiences, and gives them a voice in the public sphere. The beautiful thing about evaluation is that it too gives people a way of documenting their experiences, and can potentially create more impactful and meaningful opportunities for them to have a voice in policy conversations.

Stay tuned for more posts on evaluating advocacy, the organizations doing similar work, and some best practices.