June 8, 2016

How the Innovation Paradox Rocked My World

By Bellwether

Share this article

When my colleagues Kelly Robson and George Mu and I began a project to measure innovation in a city’s education sector, we knew it was going to be challenging. Innovation isn’t a single thing; you can’t just go out and count innovation. Instead, it’s a combination of many factors, some of which matter more than others.

So we created a composite indicator, a macroeconomic tool that is formed when individual indicators are compiled into a single index, based on an underlying model of the multi-dimensional concept that is being measured. Composite indicators are commonly referred to as indices. They measure concepts like competitiveness, sustainability, and opportunity. We call ours the U.S. Education Innovation Index.

Some of the categories that we included are novel like District Deviation and Dynamism (topics for other posts). Others are more predictable, like innovation-friendly policies and the level of funding available for innovation-specific activities.

However, one category continues to disorient me. It isn’t unusual. I read about it every day. It’s something one would fully expect to see in a measure of a city’s education sector, yet it requires an explanation to anyone who has interrogated our methodology: Student Achievement.

How we ultimately decided to measure student achievement was the product of hours of discussion and analysis. At first, we considered it an output of innovation. “Makes sense,” I thought. If you turn up the dial on innovation activities, new solutions emerge, and then student achievement goes up.

I was content with our tidy framework of inputs and outputs until Julia Freeland Fisher, director of education at the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation, and Matt Candler, founder and CEO of 4.0 Schools, introduced me to the innovation paradox and blew up my well-laid plans.

What I was missing was the relationship between success and the motivation to innovate.

Innovation, especially disruptive innovation, is more likely to happen in cities where student achievement is low. In theory, poor or declining student achievement is likely to embolden entrepreneurs and catalyze innovation. In cities where student achievement is perennially low, policymakers and education officials may feel pressure to try new tactics or adopt new policies or methodologies, and thus embrace innovative ideas.

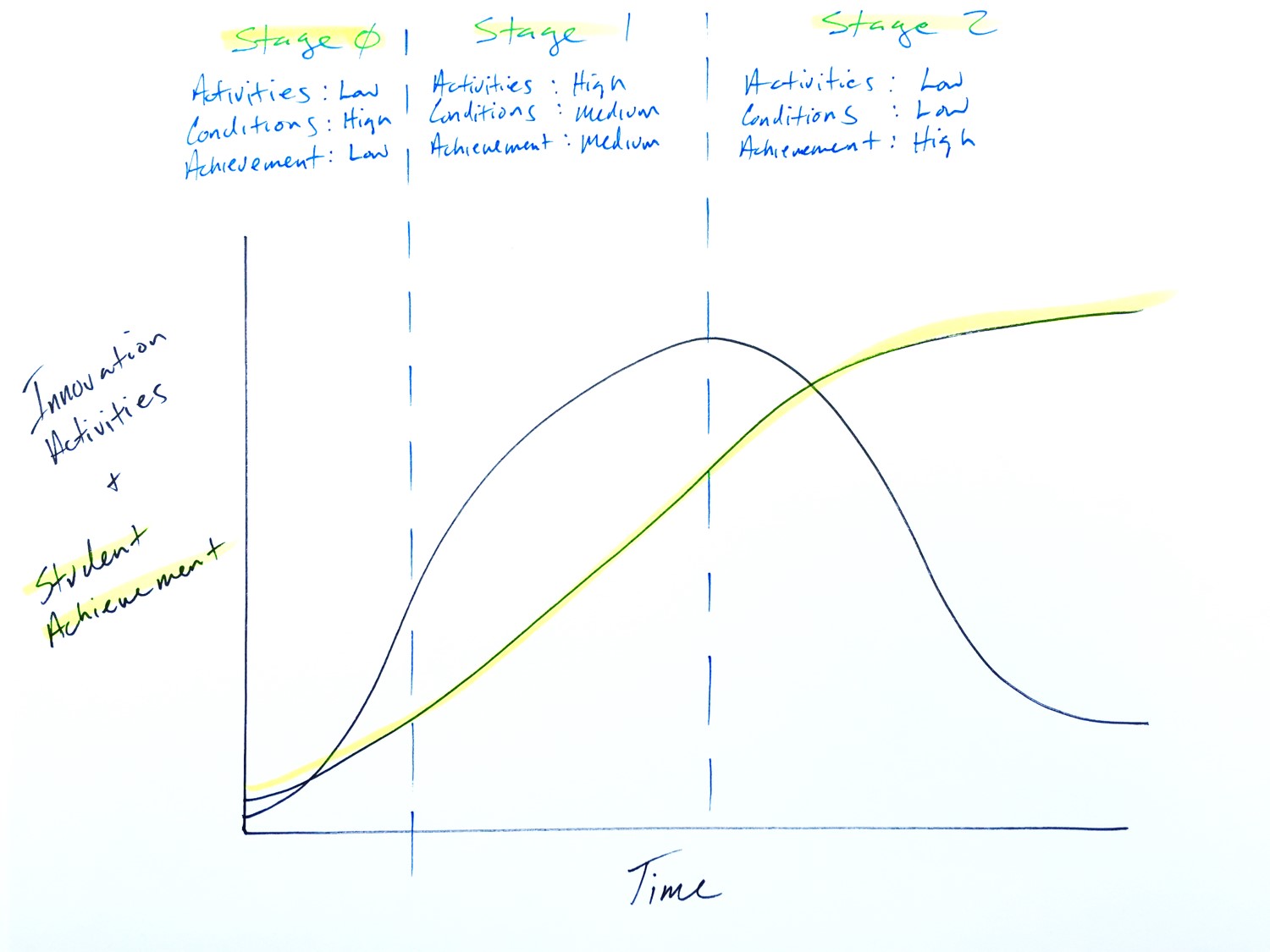

I sketched out what the relationship might look like on a graph above. It’s not as cool looking as Candler’s sketches, but shows the time lag between the implementation of innovation activities and how they should increase student achievement.

The paradox emerges in stage two where innovation activities decline as student achievement remains high. In cities where schools are consistently performing at a high level or are improving steadily, officials may be hesitant or reluctant to change anything out of fear of reversing a positive academic trajectory.

Entrepreneurs are motivated by an underperforming status quo. Innovation requires people dissatisfied with their options. When things are hunky-dory, entrepreneurs have a more difficult time proffering new ideas.

This rationale turned our Student Achievement measure on its head in three ways.

First, we changed it from an output to a condition. This shift is important because it redefines student achievement from an end goal to a circumstance to which people respond. While not mutually exclusive, the latter is more important when measuring innovation.

Secondly, we inverted our scoring so that cities with low student achievement score higher on this indicator. The technical fix was simple, but I’m still mucking through the mindset shift. Thinking about low student achievement as a positive condition for innovation encouraged me to look at urban education in a new way. Instead of reflexively feeling despair and an urge to “fix” whatever is “broken” with massive policy overhauls, I’m also starting to see opportunities for small-scale, grassroots trials in our most challenging urban schools.

Lastly, we changed the name of the category to “Need for Academic Improvement,” which suggests that a high score in this area signals a high need for improvement rather than high achievement levels.

Although we have a solid rationale for designing this measure, it still takes me a minute to make sense of it. When you go to work every day to see student achievement increase and gaps close, it’s difficult to comprehend a city scoring highly on a measure because of these measures going in the opposite direction.

We’re continuing to iterate on the index methodology, so how we think about student achievement relative to innovation may change. But right now, I’m appreciative to have colleagues who challenge my fundamental beliefs with research, data, and expertise. My hope is that the U.S. Education Innovation Index we’re developing does the same for others so more kids have access to promising new education solutions.

If you’d like to learn more about the U.S. Education Innovation Index, email me at jason.weeby@bellwether.org. If you dig Matt and Julia’s work, follow them on Twitter @mcandler and @juliaffreeland. I’m at @jasonweeby.

More from this topic

Meeting the Moment: How 4 Philanthropic Foundations Are Stepping Up Right Now

Teaching Interrupted: How Federal Cuts Threaten a Promising Teacher Residency Program

Does Increasing Graduation Requirements Improve Student Outcomes?

No results found.