Former Bellwarian Jason Weeby, who helped to develop and lead our work around education innovation, offers a series for Ahead of the Heard that makes the case for maintaining some pandemic-era education innovations. Learn more about Bellwether’s work here. Read more posts in this series here.

Former Bellwarian Jason Weeby, who helped to develop and lead our work around education innovation, offers a series for Ahead of the Heard that makes the case for maintaining some pandemic-era education innovations. Learn more about Bellwether’s work here. Read more posts in this series here.

To make a sailboat tack to sail into a headwind, the sailor must execute a specific set of motions in sequence to avoid being hit by the swinging boom or tipping over. On large sailboats, multiple crew members must act in concert to change directions successfully. The same is true for education leaders who want to create an environment where good ideas that emerged during the pandemic can be proven out and, hopefully, benefit the students who need them the most.

For any changes to schools and systems to take root and remain durable, district and charter leaders, policymakers, parents, and funders will need to act in concert over the next 6-12 months. Here’s a proposal for where to begin.

Start With the Needs and Desires of Students and Families

For innovations to stick, they can’t just be different from the status quo: they have to confer some advantages over it. The best advantage that we can hope for is improved academic and life outcomes for low-income, Black, and Latino students.

We should be conducting empathy interviews to understand what parts of school families are eager to go back to, what’s surprised them, what could be better with a little improvement, and what they’d happily leave behind once the pandemic is under control. (Look for a toolkit on the topic coming from The Learning Accelerator this month.) It’s in these answers that a new normal will emerge. We should extend our human-centered inquiry to create education policies informed directly by the people that will be most affected by them. Educators and innovators choose to spend their time and energy should stem from students and families’ needs and desires rather than pre-baked agendas, efficiency ploys, educator convenience, flashy ideas, or funders’ whims.

This approach has two distinct advantages. First, we’ll articulate more accurate definitions of problems and more relevant solutions through regular interactions with students and families. Second, it builds trust with a constituency that has a massive influence on determining which innovations are adopted, leading me to my next tack.

Activate and Organize a Natural Constituency — Parents — to Influence Policies

A few months before the pandemic, I attended a meeting of San Francisco parents advocating for better schools in Southeast San Francisco. Through an interpreter translating Spanish to English, I heard a common frustration of an inability to know the quality of curricula and instruction in their children’s schools. Principals and teachers were keeping parents at arm’s length to avoid scrutiny. Now, those parents and millions more like them have been exposed to their children’s education as lessons occur in their living room and instructional materials are a click away. Parents unhappy with the level of communication, quality of instruction, or rigor of curricula will be looking for better opportunities for their kids.

More privileged parents used private schools, pods, or online platforms to curate the kind of personalized learning experience they wanted for their children. It may have been the first time they had to confront their opportunity hoarding as they accessed resources out of reach for other families.

Both cases point to a natural constituency just waiting to be activated and organized.

And organization is key. As Bellwether’s Andy Rotherham recently put it, “A basic rule in politics is organized and focused power beats disorganized sentiment most of the time.” States, districts, and teachers’ unions are organized and focused in most places. With the exception of some community-based organizations and newer outfits like the National Parents Union, parents are not. Harnessing the energy from parents who want to improve school systems will require them to have their own organizations. Reformers will have to broaden their tent to include them, engage them in authentic dialogue, seek common ground, and act together where there are common interests.

In their seminal book on the history of education reform, Tinkering Toward Utopia, David Tyack and Larry Cuban note that many challenges to traditional schooling fail because proposed changes are too “intramural.” That is, they’re popular among reformers but lack political sway and are out of touch with families and the broader citizenry. This has been the education reform community’s blind spot for decades as well-intentioned, highly educated, and mostly white people tried to create better education opportunities for students who did not share their advantages.

Genuine inclusion requires patience, a characteristic not usually demonstrated by funders and leaders who love to say that they are driven by urgency. This tension introduces the risk of tokenizing parents and students to advance an agenda that can erode trust and stymie promising improvement efforts. However, when done well, parents and educators working together can create more responsive schools and systems and build a powerful bloc for future political battles.

Advocate for Federal and State Governments to Lead on Education Innovation

In its first days, the Biden administration is trying to pass a massive $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package that includes $130 billion to help K-12 schools reopen safely and “meet students’ academic, mental health and social, and emotional needs in response to COVID-19.” Despite its massive price tag, Biden’s proposed relief package is a short-term solution that will only cover costs through the summer. Even so, Biden’s nominee for Secretary of Education Miguel Cordona should require SEAs to set aside 1% of current and future coronavirus relief funding to find, test, and spread promising education innovations, and provide them with guidance for how to do it. Districts should be encouraged to do the same.

Relief bills are necessary to meet the crisis’s needs. Still, schools will need more federal leadership to address the learning loss that will affect millions of students for years — an Operation Warp Speed for education.

An obvious place to start would be to provide clarity and guidance to SEAs addressing which flexibilities they will retain for the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years. Without it, states and districts can’t plan thoughtfully for recovery and for leveraging innovations. Unless and until they have the confidence and funds to continue to innovate, the implicit message will be to wait for the pandemic to subside and default to pre-pandemic schooling.

The origins of Biden’s campaign slogan, “Build Back Better,” could provide a helpful roadmap for a larger initiative. The phrase dates back to the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction adopted by the United Nations in 2015. The concept of building back better is “an approach to post-disaster recovery that reduces vulnerability to future disasters and builds community resilience to address physical, social, environmental, and economic vulnerabilities and shocks.” In other words, it’s foolish to rebuild the same infrastructure in the wake of a disaster; the next version should be an improvement. Applying this approach to America’s schools would necessitate fostering innovation or running the risk of building back an inequitable school system.

Cordona could make innovation a priority of his new agenda by beefing up the Education Innovation and Research program and finally starting up the much talked about but never actualized ARPA-ED R&D initiative. The Department of Education could play a lead role in creating shared principles, language, standards, and framework for education innovation and provide SEA’s with guidance on how to implement innovation practices. If Biden triples Title I funding as he’s promised, SEA’s could use their school improvement set-aside for innovation activities. Additionally, they can play more of a support role by waiving onerous regulations that constrain innovation activities and creating strategic partnerships with organizations that can provide technical support for finding and rigorously testing new ideas.

Building the federal innovation and R&D apparatus so that it’s responsive and rigorous is a challenging task by itself. Results from the Investing in Innovation program (i3) were mixed and translating an approach that works in health care and defense isn’t straightforward. Even so, if the administration is up for the challenge and goes in eyes wide open, it could leverage the Democratic in control of Congress, increased federal funding, and the country needing new ways to accelerate student learning to build the federal engine for education innovation.

Step Up Philanthropic Investments in Innovation and R&D

Private foundations could be playing a much larger role in education innovation than they are. In fact, funding R&D and innovation is one of the main roles of philanthropy in a democracy. According to Paul Vallely, author of Philanthropy – from Aristotle to Zuckerberg, philanthropy has three vital functions: “It can support the kind of higher-risk research and innovation generally avoided by government and business. It can plug gaps left by market failure and government incompetence. And it can fund the nonprofits that mediate between the individual, the market, and the state.” Yet most philanthropies fund established nonprofits, essentially ignoring people with novel ideas who need support to test and refine them. This isn’t a new observation.

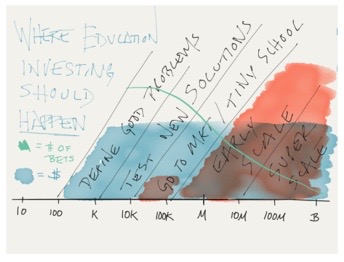

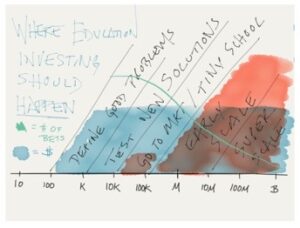

In 2015, Matt Candler pointed out that philanthropy was largely neglecting the first three stages of innovation: defining good problems, testing new solutions, and going to market. Not much has changed in the last five years. Without more foundations out there providing $1,000 to $250,000 “dream capital” grants, good ideas will die on the vine. Teachers who have developed new methods during the pandemic will never have a chance to share them. Principals who want to pilot new school models that combine the best of distance and in-person learning won’t have the chance to prove their concepts.

The good news is there are already good examples of effective seed funders who can help build the capacity of the sector, such as NewSchools Venture Fund, New Profit, and the Draper, Richards, Kaplan Foundation. An established foundation allocating 10% of their giving to seeding the sector with new ideas with follow-on funding for those that prove effective would catalyze education’s innovation engine.

Private philanthropy should also fund R&D projects that combine basic research, applied research, and experimental development. When ARPA-Ed failed to materialize under the Obama Administration, the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation teamed up to launch the $50 million EF+Math Program, which provides grants for multi-year projects to “co-design and develop new approaches to build math-relevant executive function skills during high-quality math instruction.” Endeavors like this are more complex and time-consuming than funding entrepreneurs with promising ideas, so they require big money and patience.

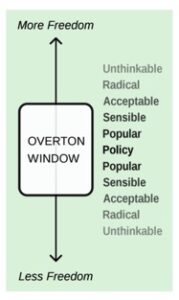

Act While the Overton Window is Open

Although the timing for any effort precipitated by a public health crisis is difficult to describe as “good,” we’re at a moment when ideas that were politically or socially unacceptable only a year ago are now safe for system leaders and politicians to pursue. In other words, the Overton Window is open. In less than a year, the concept of learning from anywhere at any time has moved from being radical to acceptable and even sensible for many families. Educators should be advocating to carry over innovations into the post-pandemic world now as vaccines roll out, scientific consensus builds for returning to in-person instruction, districts are planning for the fall, and new practices have had enough time to show some evidence of improving achievement, equity, or efficiency.

The popularization of new practices and their enshrinement in public policies will likely take much more time, familiarity, and evidence. That’s okay. In the short-term, the focus should be on maintaining the conditions that can allow teachers and principals to test new ideas. Securing waivers from local, state, and policies that give schools the freedom to experiment while holding the line on evidence of success and accountability is an immediate commonsense goal. The broader political landscape matters a lot here. It may be difficult for education issues to earn legislators’ attention while the pandemic rages; childcare, healthcare, and economic stability are at the forefront of people’s minds; and racial divisions deepen. Again, linking education initiatives to these issues will be important for their success.

When it comes to clearing a path for promising education innovations, time is clearly of the essence. A common aim, communication, cooperation, and action are all necessary too. Can policymakers, funders, and education system leaders come together to make it happen? I look into it in my final post of the series.

You can read more from this series here.