The headline “Florida teacher evaluations: Most everyone good or very good” in last week’s Orlando Sentinel felt like déjà vu. Similar headlines have graced the pages of local newspapers across the country, leading readers to assume that recent reforms of teacher evaluation systems weren’t worth the effort because teachers continue to receive high ratings. But that first impression is incomplete.

The headline “Florida teacher evaluations: Most everyone good or very good” in last week’s Orlando Sentinel felt like déjà vu. Similar headlines have graced the pages of local newspapers across the country, leading readers to assume that recent reforms of teacher evaluation systems weren’t worth the effort because teachers continue to receive high ratings. But that first impression is incomplete.

My colleague Sara Mead and I grappled with this idea in a recent report. At first blush, it’s true that reformed teacher evaluation systems haven’t substantially changed the distribution of teacher evaluation ratings. And there are logical explanations for those results.

But focusing purely on the final evaluation ratings misses important progress underneath the overall results. For example, my colleague Chad Aldeman highlighted a few specific places where teacher evaluation reforms served broader school improvement efforts. The progress does not stop there. The following studies point to other positive outcomes from teacher evaluation reform:

- Greater job satisfaction among effective teachers. A new study of Tennessee’s teacher evaluation system released earlier this month found that when teachers receive higher ratings under the state’s reformed teacher evaluation system, the perceptions of their work improve relative to teachers who received lower ratings.

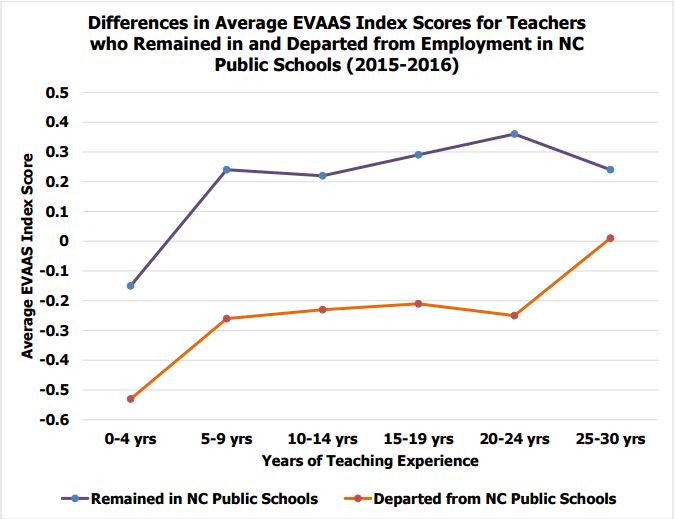

- Higher turnover of less effective teachers. A 2016 report on the state of the teaching profession in North Carolina found that, for teachers at every experience level, those who left the profession had lower overall evaluation ratings and lower effects on student growth than teachers who stayed. The graph below shows the picture for student growth. The blue line shows the growth scores for teachers who remained as teachers in North Carolina, and the red line shows those who left. We don’t know if this is a story of correlation or causation, but at least North Carolina can now point to data showing that they’re retaining the best teachers.

- Higher turnover of less effective probationary teachers. Similar to the outcomes in North Carolina, a 2014 study of New York City public schools found that teachers who had their probationary periods extended — that is, who were told they weren’t effective enough at that time to earn tenure — voluntarily left their teaching positions at higher rates. Although New York wasn’t actively dismissing low-performers, this notice was enough to “nudge” them to consider other professions.

- Improvement of overall teacher quality. A study of DC Public Schools’ (DCPS) teacher evaluation system, IMPACT, shows that the evaluation system encouraged the voluntary turnover of low-performing teachers. When the lower performing teachers left the district, leaders in the district filled the open teaching positions with new teachers who were more effective than the ones who left. The result has been a rise in overall teacher quality in DCPS.

These and other teacher evaluation studies are complicated. They are not prone to eye-catching headlines. But nonetheless, teacher evaluation systems may be quietly having an effect on which teachers stay in the profession and, ultimately, whether students are learning.