Read more live coverage of #EDlection2016 via Bellwether and The 74’s Convention Live Blog.

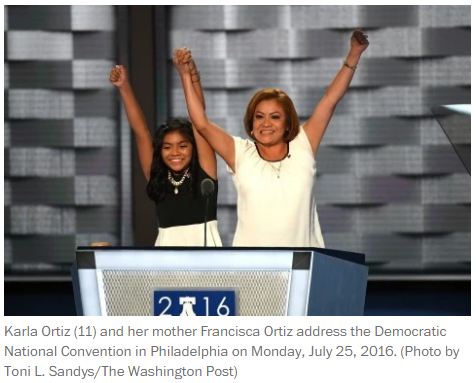

The DNC kicked off Monday night with two parallel stories of immigration that are meaningful, especially for those closely watching education issues. Karla Ortiz — a 10-year-old American citizen — spoke along with her mother, Francisca Ortiz, who is undocumented.

Another speaker, Astrid Silva — identified on the schedule simply as “DREAMer” — is the organizing director at the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada. She is also undocumented. Although these speakers highlighted the importance education played in their personal stories, it might not be immediately obvious that momentum around immigration reform in the federal executive office is explicitly connected to our schools.

The appearance of these speakers on night one suggests that the Clinton campaign intends to bring renewed energy to passing the DREAM Act, now more than six years old. And while this statute is a federal immigration law, it has enormous implications for state education programs. Since 1982, undocumented students have been entitled to attend a public K-12 school; they also cannot be excluded from public college or university. But what they still can’t do is qualify for in-state tuition or get federal grants or loans to pay for it. Some states have taken up the cause and created their own state funding opportunities — but programs vary wildly with different eligibility requirements and benefits available.

By leading with two stories that are about both immigration and education, the DNC sets the stage for some high-level ideological and policy friction between the federal government and the states. Immigration policy belongs to the federal government alone (even though we’ve seen lots of states try to assert their power — and lose). Education policy is primarily a state responsibility, even though the federal government can offer incentives for states to adopt preferred policies or practices. But the recent passage of ESSA shifts even more decision-making power to the states, while still providing them with federal dollars.

There’s also the matter of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals): a separate federal executive action that applies to this same category of undocumented people: young people ages 15-31 who are enrolled in, or recently graduated from, high school. DACA acts as an interim measure while the DREAM Act winds its way through Congress, protecting eligible students’ continued U.S. residency by allowing them to apply for a two-year reprieve from the threat of deportation.

The success of DACA, however, rests on our public K-12 schools.

In order to qualify for DACA protection, students must prove that they are attending (or have graduated from) a U.S. high school. That requirement means more than just gathering the paperwork, it also means that we’re trusting our schools have the capacity to support these students through high school.

Threading the needle — not only on immigration and education, but also state and federal authority — is going to be a tricky task. But the Clinton campaign seems to be gearing up for it. We’ve gotten a lot of the “why” now I think we’re all ready to hear the “how.”

July 27, 2016

Immigration is an Education Issue

By Bellwether

Share this article

More from this topic

Meeting the Moment: How 4 Philanthropic Foundations Are Stepping Up Right Now

Teaching Interrupted: How Federal Cuts Threaten a Promising Teacher Residency Program

Does Increasing Graduation Requirements Improve Student Outcomes?

No results found.