This is the second time I’ve written this post, and not because I enjoy doing things twice. But in the short window of time that my editor worked through my first draft, a group of six-year-olds shredded my hypothesis. I’ve never been so happy to be wrong.

Let me explain. Yesterday, a dear friend posted something on Facebook that drew me in. Now a first grade teacher, she taught my own twin boys in preschool and wowed me with her ideas, insights, and ability to be an effective communicator with both 4 year olds and their adults. But with her post, I suddenly had a bone to pick: “How’s this for honest?! My teacher friends can relate, I’m sure… week before report cards AND AIMSweb = assessment city! Poor kids : (“

Then she added a photo of what greeted her students as they entered the room tha t day: “Dear friends, Guess what we are doing today….that’s right, more testing! Do you like taking tests?” (followed by the option to indicate ‘Yes’ or ‘No’)

t day: “Dear friends, Guess what we are doing today….that’s right, more testing! Do you like taking tests?” (followed by the option to indicate ‘Yes’ or ‘No’)

As a believer in the power of data to refine and personalize instruction and also someone who is perhaps a bit weary of the pushback on assessments, I assumed this question had been designed as a big old “No” magnet. How many little (or big) people would endorse the taking of tests? This, I felt, was not the right question, because the intention of assessment is not to take tests, but rather to get feedback.

I pulled out my blog-entry soapbox and began:

“The process of engaging in assessment is the process of capturing information that is critical to the instruction. As I have often said when talking about this topic with other professionals as well as with parents at my kids’ bus stop, one assessment a year is arguably ‘too much’ assessment if the data are not used wisely to enhance how our programs are designed, what learning experiences our children are having in school, and nuances to the instructional process. Alternatively, quick, rapid assessments that are done daily are not necessarily ‘too much’ assessment if the resulting feedback provides information to the teacher and yes, the student him/herself, allowing both to detect learning, providing incentives to press on, and indicating when a change may be needed.

Assessment is a means to detecting learning and student needs. It’s not the only version, but indeed an important version, of how educators can reflect on their own practice. If assessment is the enemy, and if assessment data are discounted, we lose opportunities to understand the developmental trajectories of our students and, importantly, to guide the professional and organizational trajectories of our teachers and schools.”

I then commented on my friend’s Facebook post with a suggested reframing of the question to her students: “Dear friends: Today we get to see how much you have learned. Do you like seeing your progress?” (followed by ‘Yes’ or ‘No’) This, I thought, would provide the real feedback we need.

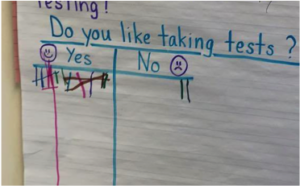

Here’s how these kids destroyed my assumption: most of them said they like taking tests. They sure showed me.

I called my friend last night to thank her for her inspiration that day, to confess my wrongs, and to pick her brain. Why, I wondered, did the kids say they liked taking tests? What she told me reinforced what I know and believe about assessment when it is done well and when, importantly, the information is used well.

She spoke about the “data-driven” nature of her school, and how teachers use assessments, particularly in these early elementary years, to gauge broad cognitive development and pinpointed skills. They analyze, discuss, display, and review data related to academic and behavioral goals. Her students are not simply targets of assessment. They help manage it and are consumers of the results. That’s right, little ones as young as six help set the ground rules for managing their time and behavior during assessments, are told how they are doing on them, and are given the opportunity to visualize and discuss their progress. There’s nothing new to the concept of self-directed learning; maybe a component of this approach involves bringing students in to the assessment of their learning.

My friend’s Facebook post? It was a “wink wink” to other teachers grappling with competing demands, not an assault on assessment. She told me about how much assessments have helped her as a teacher by exposing not only what her kids need, but also, with their sensitive design, detecting “hidden” capacities. For example, one of her students was displaying virtually no capacity to read words or sentences. The news was grim to my friend, and she had to communicate it to his parents. But then! An assessment detected fine-grained pre-reading skills this child had actually mastered: now there was something to cheer about and, importantly, something to build on instructionally.

She also discussed the importance of socializing data within her school through ongoing peer learning communities. At first, she said, sharing results from her teaching made her feel exposed and vulnerable. But in the right setting under supportive leadership, she and her colleagues realized they shared challenges and successes, were experiencing common barriers, had ideas to swap, and were able to collectively high-five when trend lines shifted in the right direction. They experience hope, motivation, and the desire to press on.

That’s the power of assessment. And that’s why I’m fine being wrong. Being right isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. But learning? That’s everything.

January 14, 2016

Just Say “Yes” to Assessment, and Other Revelations from Six-year-olds

By Bellwether

Share this article

More from this topic

What the Supreme Court’s Mahmoud v. Taylor Decision Means for Schools and Families

Meeting the Moment: How 4 Philanthropic Foundations Are Stepping Up Right Now

Teaching Interrupted: How Federal Cuts Threaten a Promising Teacher Residency Program

No results found.