In 2006, Denver voters approved a $25 million annual property tax increase to fund an innovative teacher compensation system for Denver Public School (DPS) teachers called the Professional Compensation System for Teachers, or ProComp. ProComp promised to align teacher pay and student learning. It’s probably safe to say that ten years later, ProComp is likely not in the place that its authors and advocates hoped it would be.

Soon Denver Public Schools and the Denver Classroom Teachers Association will negotiate changes to ProComp and how DPS teachers are paid. Not so serendipitously A+ Colorado, a Colorado research and advocacy organization, is out with a new report that details the history of ProComp and offers recommendations for improving it.

It’s worth analyzing the results of ProComp and considering its future because the system was at the forefront of attempting to connect teachers’ compensation to students’ academic achievement. With help from federal programs like the Teacher Incentive Fund, many districts have since tried similar teacher compensation tactics and others are in negotiations to give it a go. Why? Just like in any other profession, compensation is an incentive employers can use to attract, retain, and leverage human capital talent. But in education, there are a lot of complicating factors that make changing compensation structures difficult. So learning lessons from performance-pay system pioneers like Denver’s ProComp is useful for all districts doing this work.

Here are a few reasons why ProComp isn’t living up to its promise:

It’s unclear if ProComp impacts student achievement. Student achievement in DPS is up from 2006. But there is little evidence that ProComp is a cause of rising student achievement or is even correlated with it.

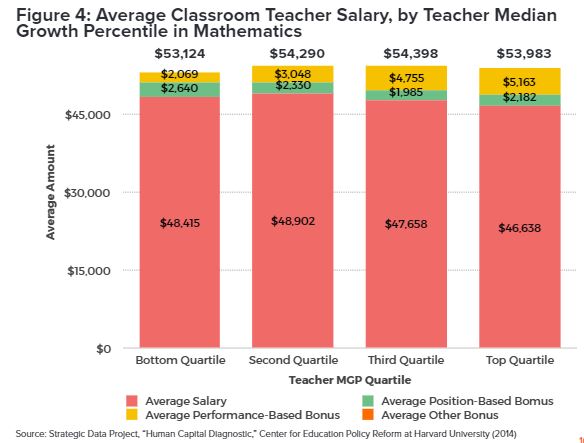

Teachers who lead students to higher academic achievement do not receive higher compensation under ProComp. One study found that due to how base salaries and bonuses work in ProComp, teachers whose students demonstrated the highest growth in math earned similar amounts to teachers whose students demonstrated the lowest growth in math.

Teachers don’t understand ProComp. DPS teachers report that they have a limited understanding of their ProComp incentives. And unsurprisingly given the above point, they perceive that ProComp asks them to do more work, and then simply repackages the same salary as a salary plus bonuses.

Given these and other findings in the A+ Colorado report, it’s clear that there is a lot to consider in the upcoming ProComp negotiations. And A+ Colorado has a lot of good, researched-based ideas for improvement like taking focus off of advanced degrees, putting more resources in high-priority schools, and aligning pay with leadership and effectiveness. These recommendations make a lot of sense and are in line with what other reform-minded teacher compensation systems do.

A+ Colorado has one potentially-groundbreaking recommendation that deserves special attention: In order to retain early career teachers and reward them during the time in their career that research shows large improvement in practice, A+ Colorado suggests increasing teachers’ salaries each year for the first five years of experience by 10 percent, with a 1 percent increase in current dollars every year thereafter up to year fifteen.

A+ Colorado is right to highlight that compensation can’t do it all. Tradeoffs need to be made, and paying teachers more earlier in their career as a retention mechanism is smart, especially in a district that loses half of its teachers within their first three years on the job. Lots of research confirms that teacher turnover is bad for schools and students. And that turnover is disproportionately high in hard-to-staff schools. At the same time, there are some adverse effects that a 10 percent automatic salary increase for all teachers during their first five years of teaching could have. For example, policymakers should consider whether this across-the-board increase could incentivize teachers who aren’t as effective to stay in the profession.

Heading into ProComp negotiations, it would be easy to look at the results of the last decade and decide to reverse course back to a “step-and-lane” teacher compensation system that most districts employ. But that would be a mistake. The best path forward is to take the sobering results as an opportunity to push forward on the promise the district made to its taxpayers and find a way to pay teachers based on their ability to lead students to academic success.