This is second in a series of blog posts and resources to offer lessons and reflections for school leaders, district officials, and education policymakers using data and stories from the McKnight Foundation Pathway Schools Initiative. The series is supported by a grant from the McKnight Foundation.

Evidence show that high teacher turnover is hurting long-term improvement efforts in many urban schools, and yet the problem remains. To ensure improvement efforts actually take hold, education leaders at the state, district, and school levels must pay closer attention to teacher turnover, examine its causes within their own local context, and develop strategies that will keep highly effective teachers in schools where they are needed most.

Developing effective strategies to retain great teachers in high-need schools first requires confronting some common misconceptions about teacher turnover. First, there is not a nationwide, generalized teacher shortage, and the profession is not shrinking. In fact, the teaching workforce grew by 13 percent over the past four years, while the student population grew by only two percent. Instead, there are acute teacher shortages in specific geographic areas, districts, and subject areas. Second, while turnover tends to be highest in urban, high-poverty schools, not all high-poverty schools have high turnover, which means this challenge can be overcome. Third, higher turnover rates in high-poverty schools are not primarily because of students’ needs. Teachers who leave their jobs because of dissatisfaction often rank organizational factors in schools — such as administrative support, salaries, lack of time, and lack of faculty influence in school decisions — higher than student factors when explaining their decision to leave.

A local program in Minnesota’s Twin Cities is an interesting case study for turnover variation. Minnesota’s teacher workforce is growing overall, though not as much as national trends: Minnesota teachers grew by 5.8 percent in the past seven years, compared with 3.2 percent growth in the number of students. But, like national trends, in many geographic areas and teaching specialty areas, hiring and retaining effective teachers can be extremely difficult. In the first post in this series, I looked at a subset of elementary schools in Minnesota’s Twin Cities that participated in the McKnight Foundation Pathway Schools Initiative. These schools’ populations included high concentrations of students who are low-income (89%), students of color (91%), and dual language learners (50%). As I summarized, teacher turnover varied from year to year and between schools. Even within the small sample of the Pathway schools, some schools had little to no turnover some years, or turnover on par with state averages. The relationship between teacher turnover and student achievement was inconsistent, nevertheless, turnover affected school improvement efforts.

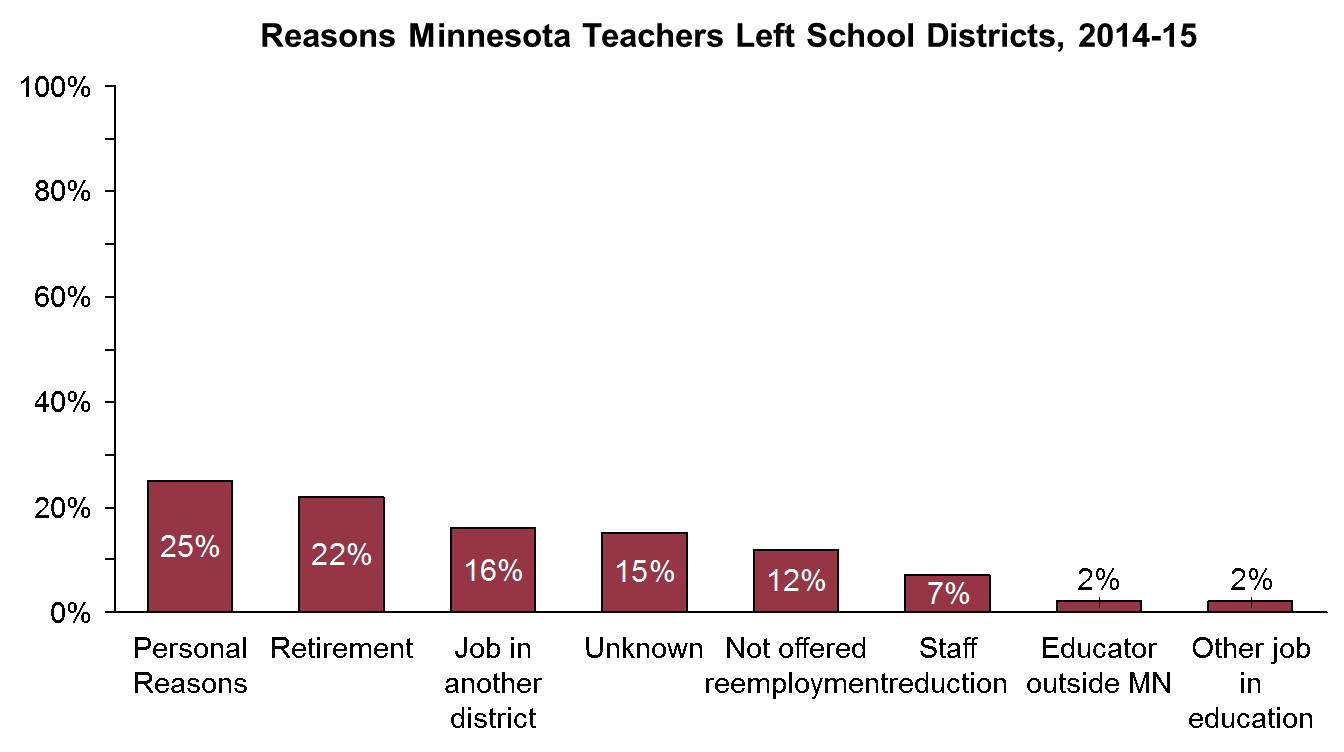

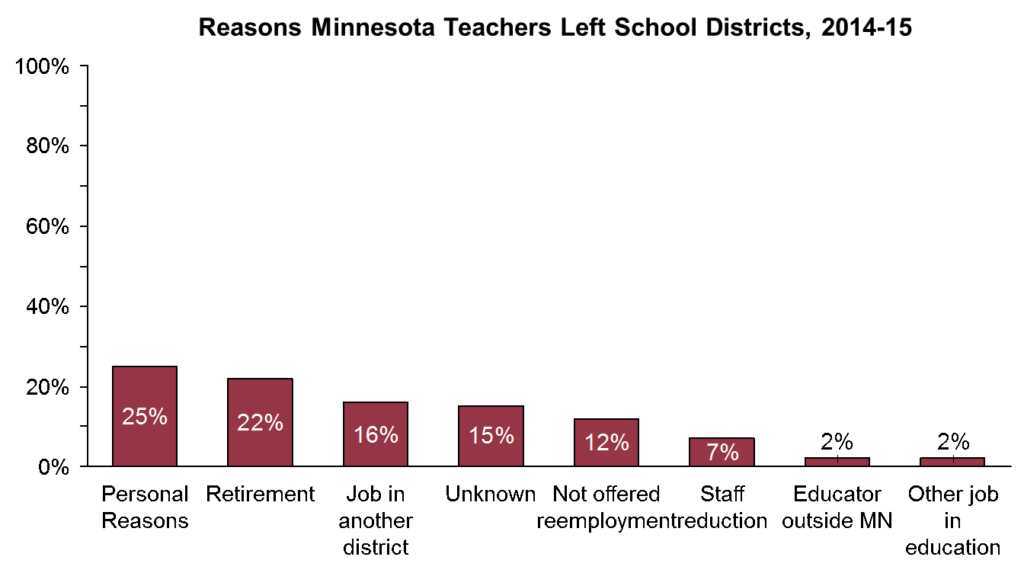

The chart below, from the Minnesota Department of Education Teacher Supply/Demand report, can give some very broad ideas of why teachers leave the teaching profession or move to another school district in Minnesota, but it provides a limited picture because it does not include teachers who change schools within their districts or change roles within their schools. Moreover, teachers’ reasons for leaving likely look very different in the high-poverty, urban elementary schools in the Pathway Schools Initiative than they do statewide.

Some of the most common reasons for leaving, according to the data available here, are personal reasons, retirement, and interdistrict competition. 40 percent of teachers leave for “personal,” or “unknown” reasons. National data suggest common “personal reasons” could include things like caring for one’s own children or dissatisfaction with school leaders and school culture. Not all these challenges can be solved completely at the school or district level, but some can. Some promising solutions, drawn mostly from national examples, and inspired by conversations with stakeholders involved in the Initiative, are:

- District Policy Incentives: It’s important for larger districts to consider how their staffing policies can impact teacher assignment and transfers, especially for high-need schools. Teacher contracts and district policies can sometimes encourage teachers to transfer schools within a district, prioritize transfers and placements based on seniority with no input from principals, or set up incentives for effective teachers to transfer away from high-poverty schools. Different district policies and contracts could account for some of the turnover differences among the Pathway schools.

- School Strategy, Culture, and Leadership: School culture, school strategy, and school leadership are huge contributors to teachers’ job satisfaction in any school. District and school leaders need strategies and tools to track the experiences that teachers and students have in schools and identify implications for turnover, student achievement, and improvement efforts. Taking surveys of school climate or culture offer one way to uncover problems before they cause turnover. The Initiative required participating districts to use the 5Essentials school culture survey across all their schools — and these revealed a wide range of teacher satisfaction and experiences. These results could open up a dialogue that gets to the heart of some stubborn turnover challenges.

- Targeted Incentives: 16 percent of Minnesota teachers leave their jobs for a teaching job in another school district. Minnesota district hiring leaders say salaries and a competitive teacher job market are their top barriers to teacher retention. To address this challenge, other district leaders could consider various kinds of performance-based pay structures and targeted incentives to retain high-performing teachers in high-need schools and subjects. Action is especially needed to recruit and retain highly effective teachers in hard-to-staff roles, like special education teachers and specialists in teaching English language learners.

- Hiring and Induction Supports: Hiring and induction supports can be key to breaking cycles of high turnover. Evidence from other school districts suggests that induction supports for newly hired teachers can increase student achievement and improve retention, and in recent years many large districts have reformed their hiring practices to put more decision-making power at the school level.

There won’t be just one solution for teacher turnover in the Pathway Schools, or other schools struggling with teacher retention. But, to move forward, school and district leaders must better understand reasons for turnover and target appropriate solutions, including, but not limited to, targeted incentives; hiring supports; district policies; and school strategy, culture, and leadership, with a strong grounding in school-by-school data.