This is the third in a series of blog posts and resources to offer lessons and reflections for school leaders, district officials, and education policymakers using data and stories from the McKnight Foundation Pathway Schools Initiative. The series is supported by a grant from the McKnight Foundation.

In recent blog posts, I’ve been looking at the impact of teacher turnover on school improvement efforts and ways schools, states, and districts can address this challenge. But what about turnover in leaders, such as principals, district leaders, and superintendents? Leaders can have a huge impact on the culture, priorities, and strategies of their schools and districts. Recent studies have found that principals had a significant effect on teachers’ overall job satisfaction, and that the quality of administrative support could strongly influence teachers’ decisions to leave or stay. Given this reality, efforts to address teacher turnover should not overlook leaders.

Despite the demonstrated importance of strong, stable leadership, leaders in urban schools and districts continue to turn over at high rates. Leadership turnover can be caused by some of the same factors as teacher turnover, such as retirement, performance issues, or competitive offers elsewhere. A single change in leadership can reverberate through a school or district, for better or worse.

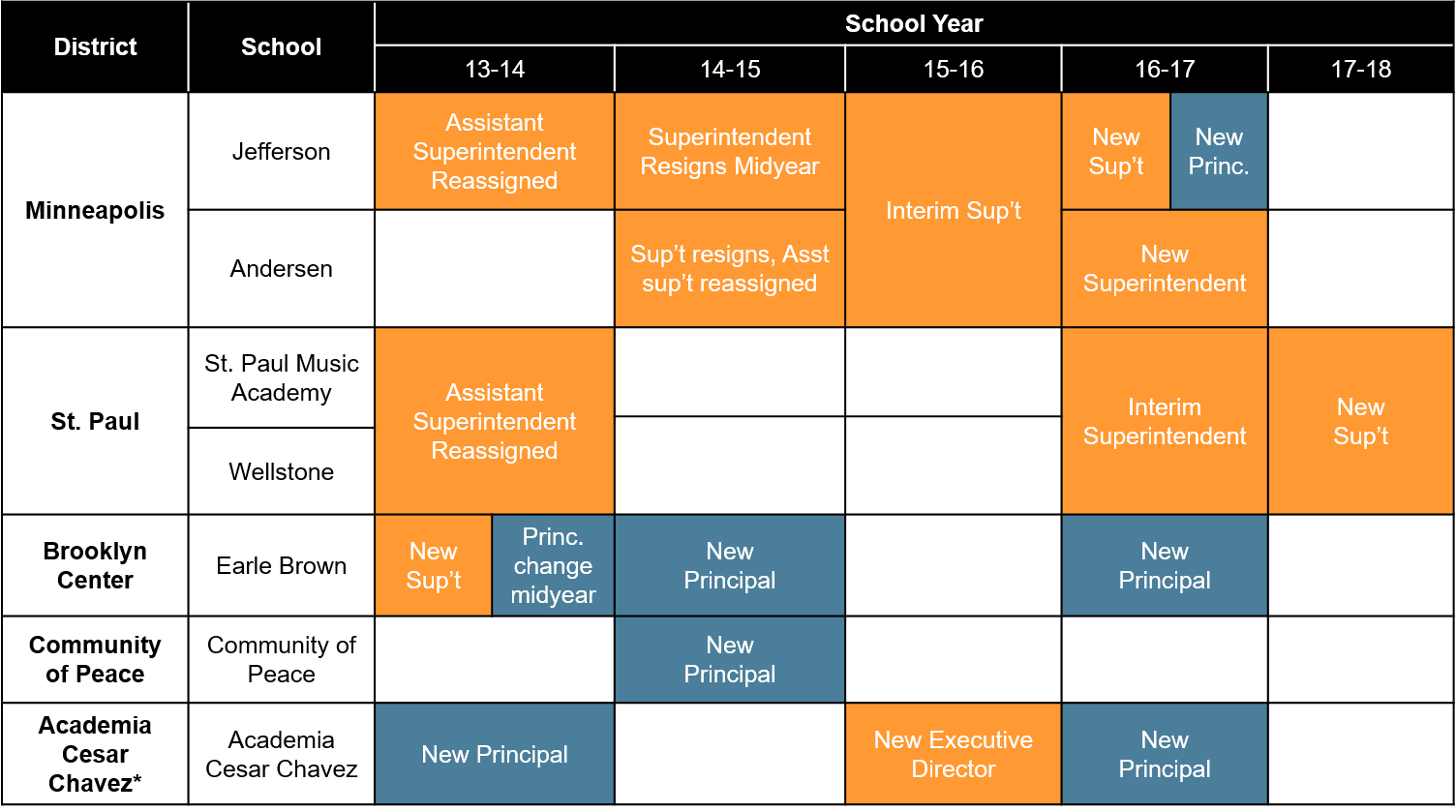

Principals in the Pathway Schools Initiative were fairly stable over the course of the Initiative. Of seven schools participating in the Initiative, three retained the same principal throughout all five years of the initiative, and two experienced only one change in principal leadership. This is unusual for high-poverty, urban schools, where principals turn over even faster than teachers. Nationally, 22 percent of public school principals and 27 percent of principals in high-poverty public schools leave annually. Two schools in the initiative, however, experienced more frequent leadership transitions — including one elementary school that had a new principal almost every year of the initiative.

Even when principals stayed the same, changes in district leadership had an impact on schools. All three of the traditional school districts in the Initiative changed superintendents and reorganized district leadership at least once. This is not surprising based on national trends: The average urban superintendent lasts barely three years, and the role of an urban superintendent is increasingly high pressure and politicized. These people were key liaisons between the Initiative partners, schools, and districts, and every time a district leader changed, it took time for their successors to build working relationships and learn about the Initiative.

Churn in district leadership is also frequently accompanied by changes in district strategies, and teachers and principals in Pathway Schools reported to SRI International evaluators that this sometimes hindered progress at the schools. Especially in the larger districts involved in the Initiative, Pathway Schools had to negotiate for the flexibility to pursue their goals differently from what other elementary schools in their districts were doing. With changes in leadership and accompanying changes in district strategies, this process had to be repeated, creating potential uncertainty and mixed messages for principals and teachers.

A change is leadership isn’t necessarily a bad thing for a district or a school — like teachers, leaders change for all kinds of reasons. Still, districts should take every possible step to retain high-performing and high-potential leaders where they can, and to simultaneously plan for succession and create a pipeline of new leaders from within their staff. Potential solutions to consider include: building a complete district framework for principal talent management, instituting school leader residencies to create effective new leaders, and facilitating smooth transitions with extra support for new leaders. Schools and students shouldn’t start from scratch when leadership changes occur.