In Bellwether’s recent From Pandemic to Progress three-part district webinar series, leaders of school districts and community-based educational initiatives joined our team to discuss the 2021-22 school year ahead. Read our summary and see the video of Part 1: Policy and Planning, here.

Since first shutting their doors to in-person learning in March 2020, school districts and community partners have had to work harder and smarter in order to communicate and collaborate with students, families, and other stakeholders. Even as more schools transition back to in-person learning this spring or fall, millions of students nationally may have had minimal or no engagement with virtual learning over the past year. What has the 2020-21 academic year taught district and community leaders about family engagement, and how might school operations change as students make a safe return to classrooms?

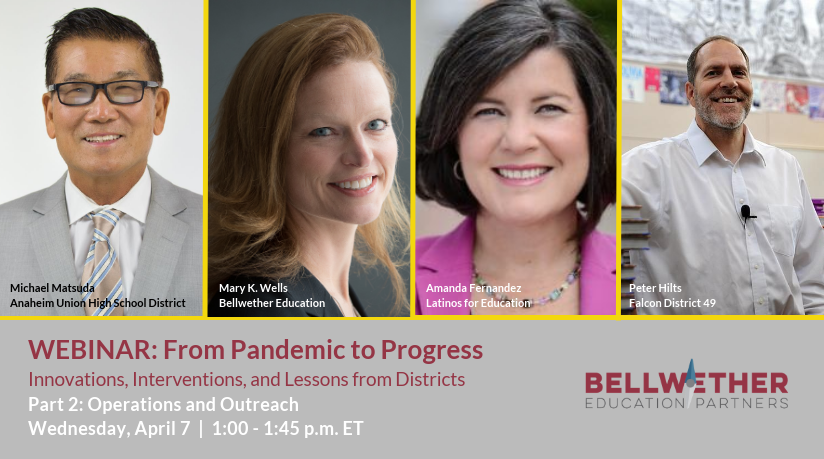

Part 2 of Bellwether’s From Pandemic to Progress webinar series focused on operations and outreach to tackle these fundamental questions. Panelists included:

- Amanda Fernández, CEO and Founder of Latinos for Education and Partner in the Boston Community Learning Collaborative, Massachusetts.

- Peter Hilts, CEO, District 49, Colorado.

- Michael Matsuda, Superintendent, Anaheim Union High School District, California.

- Facilitator: Mary K. Wells, Managing Partner and Co-Founder, Bellwether Education Partners.

The discussion (video above) led to three key takeaways:

Takeaway 1: Districts should recognize the essential role community-based organizations can play in connecting schools with families and communities, and in expanding district capacity

The pandemic, “Unmasked the illusion of independence,” within Hilts’ district that stretches across suburban and rural communities near Colorado Springs, Colorado. “We thought we operated pretty independently…but in a crisis we needed to increase the tempo of our collaboration,” and work with neighboring school districts and community organizations to execute on initiatives like a regional free meal distribution strategy, he noted.

Similarly, Matsuda highlighted the value of community partnerships over the past year, which have helped his district build relationships with families in new settings and get the word out about community public health initiatives such as COVID-19 tests and vaccinations. “We need our faith-based communities, our nonprofits, and our schools working together to build trust,” especially with communities of color and immigrant communities, according to Matsuda. He noted that these new partnerships shouldn’t just be temporary, “And will make us much stronger as institutions.”

Fernández saw these dynamics play out from a different angle in Boston, where her organization is one of the leading partners in a community-based effort to launch more than a dozen free, in-person, small-group learning pods serving mostly Black and Latino children. “The pandemic has surfaced a need for equal partnership at the table between families, community-based organizations, and schools, which will contribute to better outcomes for students.”

Each of the organizations in the Community Learning Collaborative built trusting relationships with different groups of families over the years. These existing relationships served as a foundation for recruiting families into the pods and providing a safe, supportive learning environment. According to Fernández, “Trust, collaboration, and centering students and families have all been consistent in the approach we’re taking,” to running the pods.

Takeaway 2: Inclusivity and equity are essential to successful outreach efforts

As learning conditions and district offerings evolved rapidly over the last year, it was essential to keep families in the loop and informed. However, traditional venues for communication like parent-teacher nights, flyers in backpacks, or in-person conversations were off the table. Successful communication strategies in this new environment prioritized inclusivity and equity, multiple modes of communication to reach families wherever they were, and a focus on listening to families’ needs and priorities.

Matsuda noted that families in his district speak more than 40 languages. Beyond translating communications, his district also worked to anticipate and facilitate two-way conversations with families in their preferred language.

One of the ingredients for success in the Boston Community Learning Collaborative, according to Fernández, was intentionally recruiting mostly Latino and Black educators and staff to supervise the pods. These team members often came from the same communities as the children they served and were well-positioned to quickly build communicative, trusting relationships with students and families.

Takeaway 3: What families and students are looking for from school may have shifted permanently

Experiences of the past year, both positive and negative, have changed many students’ and families’ goals and expectations from schools. Panelists were optimistic about near-term opportunities to bring a renewed sense of urgency to educational innovation. They also agreed on the importance of partnerships among districts, higher-education entities, employers, and community-based organizations to meet students’ needs in new and better ways.

For example, Hilts anticipated that an increasing number of districts would offer, “A mix of online learning and flexible schedule options, because it serves our students, their life circumstances, and their personal preferences,” especially at the high school level. “We have to be better about providing culturally and technically responsive learning options that provide access to more students.” Matsuda was also excited about this possibility, adding, “It’s not going to be easy to innovate, but the comfort level among families and students [with online learning], particularly at the high school level, has grown.” Both Hilts and Matsuda agreed that well-designed, flexible academic learning environments might increase student engagement in learning and develop deeper life skills such as self-directed time management. But they underscored that policy barriers in many states could be an impediment to these kinds of innovative offerings.

Each panelist noted that the isolating and traumatizing effects of the pandemic have made students’ mental health and social-emotional learning urgent priorities. “Families are concerned about social, emotional, and mental health,” said Matsuda, and are looking to schools to help assess, monitor, and meet those needs. Fernández reported hearing from families that mental health is a top concern and urged districts to, “Continue that kind of support and balance it with any academic support that might be needed.” All three panelists agreed that, by keeping community partners at the table, districts can deepen the web of academic and non-academic supports for students and families.

Find a video and summary of Part 1 in our From Pandemic to Progress webinar series by clicking here, and stay tuned for a summary of key takeaways from the Part 3 discussion on academics and instruction.