While traditional school districts are characterized by a relatively unchanging stock of schools, performance-based systems with effective parental choice mechanisms and rigorous school oversight are defining the changes taking place in places like New Orleans, DC, and Denver. These systems have one unique common denominator: dynamism, a central concept in modern economics that explains how new, superior ideas replace obsolete ones to keep a sector competitive.

The process happens through the entry and exit of firms and the expansion and contraction of jobs in a given market. As low-performing firms cease to operate, their human, financial, and physical capital are reallocated to new entrants or expanding incumbents offering better services or products.

Too little dynamism and underperformers continue to provide subpar services and consume valuable resources that could be used by better organizations. Too much dynamism creates economic instability and discourages entrepreneurs from launching new ventures and investors from funding them.

Dynamism, however, rarely comes up in discussions about education policy despite a growing number of urban education systems closing chronically underperforming schools and opening new, high-potential schools as a mechanism for continuous systemic improvement.

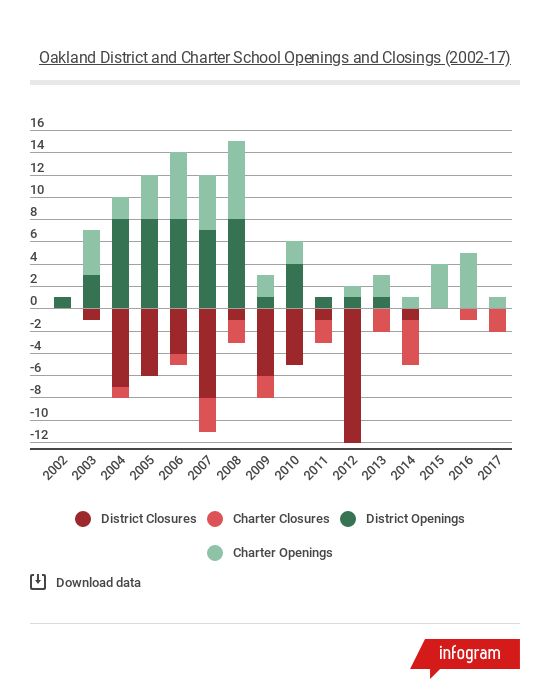

New Orleans’ system of schools has operated in this reality since Hurricane Katrina. And others like Denver and DC are implementing their own versions of dynamic, performance-based systems. To illustrate, below is a graph of charter school dynamism in DC between 2007 and 2018.

But it’s a novel study on Newark’s schools that provide the field’s best research on a dynamic system in action.

Authors Chin, Kane, Kozakowski, Schueler, and Staiger provide a look at the effects of school openings and closings between 2010 and 2016 on student learning. The study examines Newark’s changing school landscape when the city was implementing aggressive reforms that resulted in more choices for families and a large number of closures and openings.

The results are encouraging. The authors explain: “One of our main findings is that between-school reallocation of students was an important driver of improved results in Newark. The strategy of closing or repurposing the least effective schools, opening new district and charter schools, and giving families greater choice produced gains in English and offset what would have been a relative decline in achievement growth in math.” The achievement gains were larger than in similar schools in New Jersey.

In theory, dynamism is an engine for continuous improvement, and the results from the Newark study seem to bear that theory out in practice. But the education sector is different from other sectors in important ways that complicate the application of the concept. Opening schools is a herculean effort that requires strong leadership, a solid academic model, startup funding, community support, rigorous oversight, political will, and available facilities. And closing a school is not like closing an unpopular restaurant or an outmoded video rental store. Schools, even schools that fail their students academically, are valued community assets and providers of numerous stable middle-class jobs.

But even if the applications of dynamism are complicated, the concept is still worth exploring as more and more districts embrace it. According to an October 2017 report by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, 58 American cities now have 20 percent or more of their students enrolled in charter schools. And the numbers continue to grow. In addition, more districts are implementing their version of autonomous and accountable schools as an avenue to significantly improve student academic outcomes, with in-district charters, innovation zones, renaissance schools, and partnership schools. It’s worth having a robust discussion about the state-level policies and resources necessary to support smart dynamism as well as what dynamism means for communities when schools are constantly opening and closing.

Ideally, a city creating a performance-based system of schools would build the conditions for dynamism to be a positive force for students, families, and communities. For starters, that means having an accurate and empirical understanding of the quality of schools in the system, available facilities, demographic patterns, and community desires. It also includes mitigating the harm and anxiety that comes from pre-closure transfers with good communication, transparency, and better options. Students attending closing schools should be supported through and long after their transition to a significantly higher performing school. On the supply side, there need to be better options available, which means a constant effort to expand, replicate, and incubate great schools.

Here are some questions we still need to answer:

- What specific supports do displaced students need to thrive during their school transition and in the years following and what are the associated costs?

- What preferences should displaced students have in unified enrollment systems?

- What resources do families of displaced students need to make informed school choices?

- What makes for a prepared “receiving school?”

- How does a school district budget for regular performance-based closures?

- What will it take to create a sustained pipeline of high-performing school operators and school leaders?

- When are school turnarounds a better option than closures for chronically low-performing schools?

- How can system leaders mitigate the negative effects of school churn in low-income communities?

- How will communities with dynamism react to constant school openings and closings?

State and local education leaders should grapple with these questions and others when preparing for a future of dynamic systems of schools.