One of the main goals of creating and publishing the U.S. Education Innovation Index Prototype and Report was to stimulate evidence-based conversations about innovation in the education sector and push the field to consider more sophisticated tools, methods, and practices. Since its release three weeks ago at the Digital Promise Innovation Clusters convening in Providence, the index has been met with an overwhelmingly positive reception.

I’m grateful for the many fruitful one-on-one conversations that have pushed my thinking, raised interesting questions, and provoked new ideas.

Here are a few takeaways on the report itself:

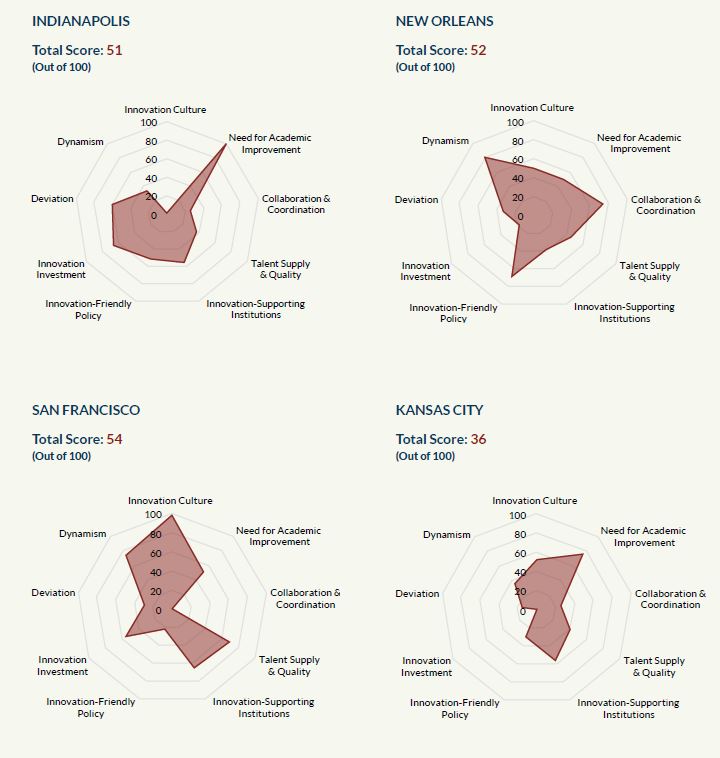

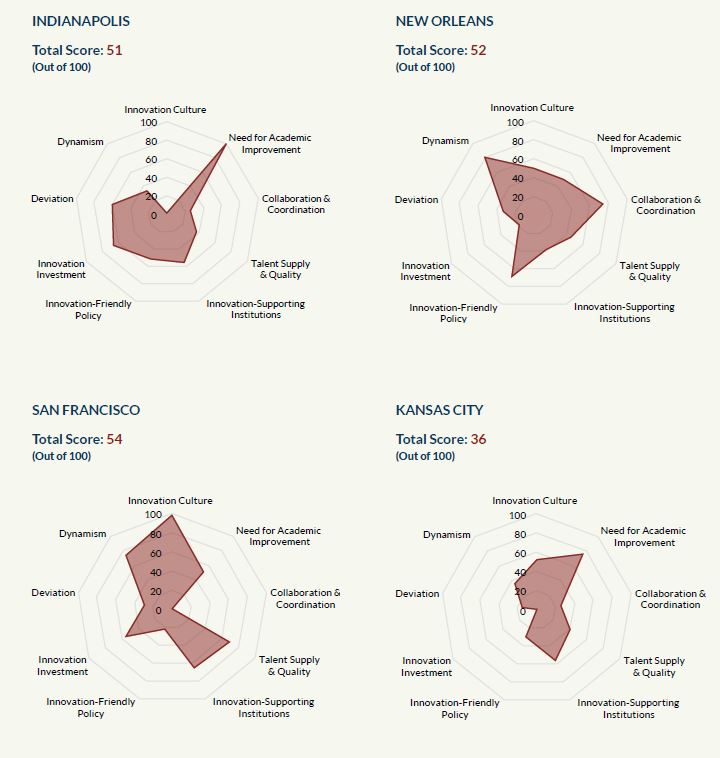

People love radar charts. And I’m one of those people. In the case of the innovation index, radar charts were a logical choice for visualizing nine dimensions and a total score. Here they are again in all their glory.

Readers weren’t always clear on the intended audience or purpose. This concern came up often and hit close to home as someone who strives to produce work that is trusted, relevant, timely, and useful. One of the benefits of the prototype is that we can test the tool’s utility before expanding the scope of the project to more cities or an even more complicated theoretical framework. So far the primary audience for the index — funders, policy makers, superintendents, education leaders, and city leaders — have demonstrated interest in learning more about the thinking behind the index and how it can be applied to their work. Ultimately I hope it will influence high-stakes funding, policy, and strategic decisions.

The multidimensionality of innovation challenges assumptions. When I explain that we measured the innovativeness of education sectors in four cities — New Orleans, San Francisco, Indianapolis, and Kansas City, MO — inevitably, the next question I get is “how do they rank?” Instead of answering, I ask my conversant for his/her rankings. I’ve had this exchange dozens of times, and in almost every case, New Orleans topped the list because of the unique charter school environment. When I then explain that the index was sector agnostic — it doesn’t give preference to charter, district, or private schools — people immediately reconsider and put San Francisco in the number one slot. What this tells me is that many people associate innovation with one approach rather than treating it as the multidimensional concept that it is. This misperception has real policy and practice implications, and I hope the index provides nuance to the thinking of decision makers.

“Dynamism” and “district deviance” are intriguing but need more research. Two of the measures that I’m most excited about are also ones that have invited scrutiny and criticism: dynamism and district deviance. Dynamism is the entry and exit of schools, nonprofits, and businesses from a city’s education landscape. Too much dynamism can destabilize communities and economies. Too little can keep underperforming organizations operating at the expense of new and potentially better ones. In the private sector, healthy turnover rates are between five and 20 percent, depending on the industry. We don’t know what that number is for education yet, but it’s likely on the low end of the range. More research is needed. Our district deviance measure assumes that districts that spend their money differently compared to their peers and are trying new things, which is good. It’s a novel approach, but its accuracy is vulnerable if the assumptions don’t pan out. Again more research is needed.

Measure more cities! Everyone wants to see more cities measured with the index for one of two reasons. The first is that they want to know how their city is doing on our nine dimensions. The second is that they want to compare cities to each other. Both make my heart sing. Knowing how a specific city measures up is the first step to improving it. Knowing how it compares to others is the first step to facilitate knowledge transfer and innovation diffusion.

Long reports are difficult to digest. Few people have time to read 80+ pages of text that explain the index and its results, no matter how interesting it is. We know that. However, we went to great lengths to explain our rationale for the index, construction process, methodology, and results to demonstrate our commitment to rigor and transparency. We also made it supremely skimmable with lots of headings and a hyperlinked table of contents. My hope is that we can build off of our solid research base so that the next version of the index is a dynamic online platform that will allow users to manipulate and visualize data that’s most important to them.

And a few takeaways on the broader landscape:

There’s an education innovation movement afoot. I had the privilege of joining top researchers and practitioners from across the country at the White House to discuss education research and development, digital learning, and the promise of advancing a national education innovation agenda. Much of the discussion was about pursuing high-impact, relevant research; disseminating results; and the federal government’s role in education R&D. It’s worth noting that the last point is not a new one, and it seems to resurface during presidential election years for obvious reasons. With ESSA shifting much of the action back to states, increasing spending on R&D seems like a natural role for the federal government. I’m clearly a proponent of the move, but I’m too skeptical to get excited about it just yet. I haven’t been privy to the complementary conversation about private philanthropy’s role in education R&D, but I hope it’s happening.

In education R&D, we’re long on research and short on development. There are legions of education researchers theorizing, experimenting, analyzing, and publishing on a daily basis in government agencies, colleges and universities, think tanks, and private companies. We’re awash in research, which is critical to advancing what we know about what works in teaching, learning, and policy. But research is slow and often irrelevant to the practice of teachers, principals, and policy makers. Development, on the other hand, is more difficult to come by. Organizations that foster innovation through prototyping and rapid-cycle evaluations are small in number but no less important to the creation of promising new approaches to education.

So far, the U.S. Education Innovation Index is accomplishing its goal to foster a more robust dialogue about education innovation, and I look forward to continuing the conversation with attendees of the Education Cities Innovative Schools Summit, Education Pioneers National Summit, and ASU-GSV Summit in the coming months, where I’ll be sharing our findings and exploring the future of innovation in education.

Email me if you’d like to host a conversation about education innovation, learn more about the index, or explore another innovation-related topic: jason.weeby@bellwether.org.

October 14, 2016

Reactions to the U.S. Education Innovation Index

By Bellwether

Share this article

More from this topic

Meeting the Moment: How 4 Philanthropic Foundations Are Stepping Up Right Now

Teaching Interrupted: How Federal Cuts Threaten a Promising Teacher Residency Program

Does Increasing Graduation Requirements Improve Student Outcomes?

No results found.