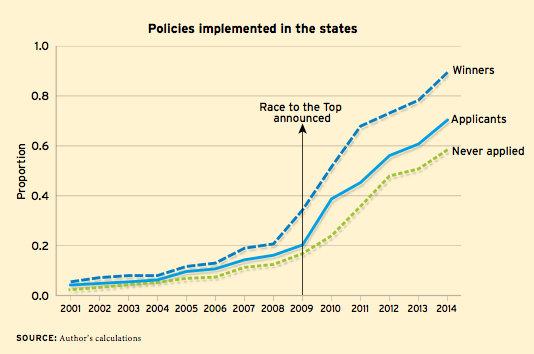

A new study released today shows that Race to the Top (RTT)—President Obama’s K-12 education competitive grant program—resulted in major changes in education policy in the states that applied for the grant, whether they walked away with $700 million or no money at all. The study, conducted by the University of Chicago’s William Howell, found that before RTT, states enacted about 10 percent of proposed reform policies. After? Sixty eight percent.

While education policy movement is usually described as incremental at best, Howell’s study found that RTT got states moving on K-12 initiatives, and fast. However, speed will likely be the Achilles heel of RTT.

Howell’s study puts RTT’s heavily-rated criteria, including school turnaround efforts, standards implementation, and teacher and principal effectiveness, in the spotlight for scrutiny. Observers need to look no further than RTT’s biggest winners—Tennessee, Florida, New York—to see that the grant greatly influenced states on all these criteria. But implementation of policies related to these criteria hasn’t been smooth sailing in large part because many of these efforts take much more time to come to fruition than the states were given through RTT.

There’s probably no better example of this than teacher evaluation—a policy area that was catapulted into implementation due to RTT dollars. RTT gave states and districts the political cover to move quickly on teacher evaluation, but once they got into the nitty gritty of implementation, movement slowed. In fact, several states delayed rollout of evaluation systems, causing political will to wane and naysayers to pounce on the opportunity to mark new systems as failures.

Issues with teacher evaluation rollout could also be attributed to the fact that due to the nature of RTT, evaluation was just one of many simultaneous reforms efforts happening at once. Among other efforts, states and districts were implementing new, more rigorous standards and assessments and professional development related to those new changes while at the same time attempting to hold educators accountable through new evaluation systems. As Joanne Weiss points out “sequencing of complex new initiative matters a lot, and Race to the Top didn’t do enough to guide states in how to think it all through.”

Due to the political controversy surrounding the rollout of these systems, holding states accountable for connecting teachers’ instruction to student achievement is all but an afterthought in federal policymaking. This is evidenced by the fact that the House and Senate neglected to include teacher evaluation in their No Child Left Behind rewrites. This means that, once again, billions of federal dollars will be given out to states for teacher effectiveness initiatives without any proof that those efforts are leading to improved instruction for students. And very few parties seem to be upset by this fact. As the Senate ESEA debates continue this week, no senator dare murmur any words of support for teacher evaluations.

Howell’s study shows that all states are doing a lot more in education than they used to, and RTT allowed speedy states to accelerate even faster than they were prior to receiving RTT funds. This suggests that competitive grant programs like RTT impact nationwide activities, but it might be a more indirect and trickle-down influence than policymakers would prefer. There will be numerous studies of Race to the Top’s effects for years to come. A study about the impact of RTT reforms on improved outcomes for students should be prioritized. Another study should take a deeper look at the number of RTT efforts sustained over time after the initial quick implementation.