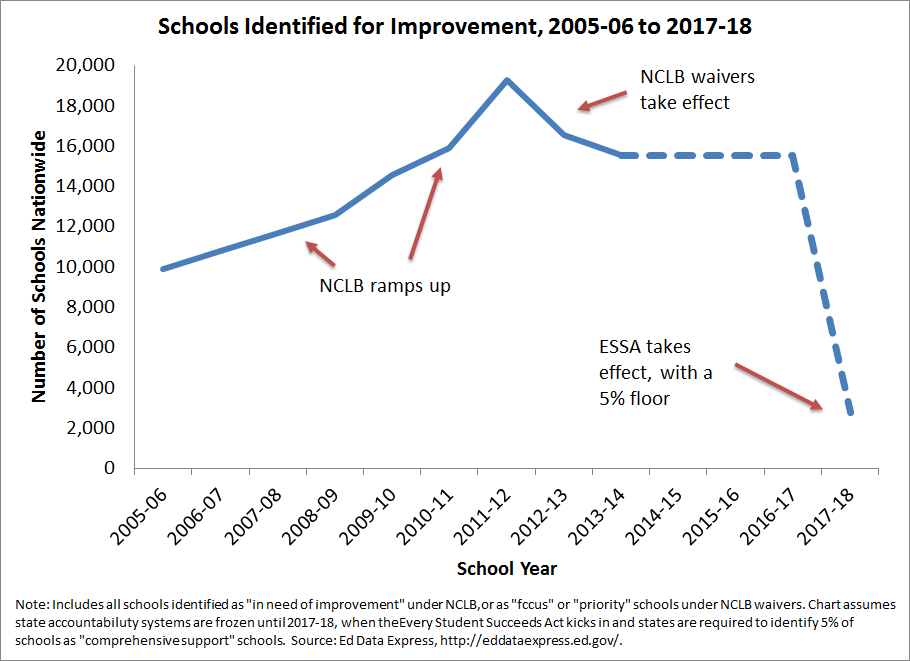

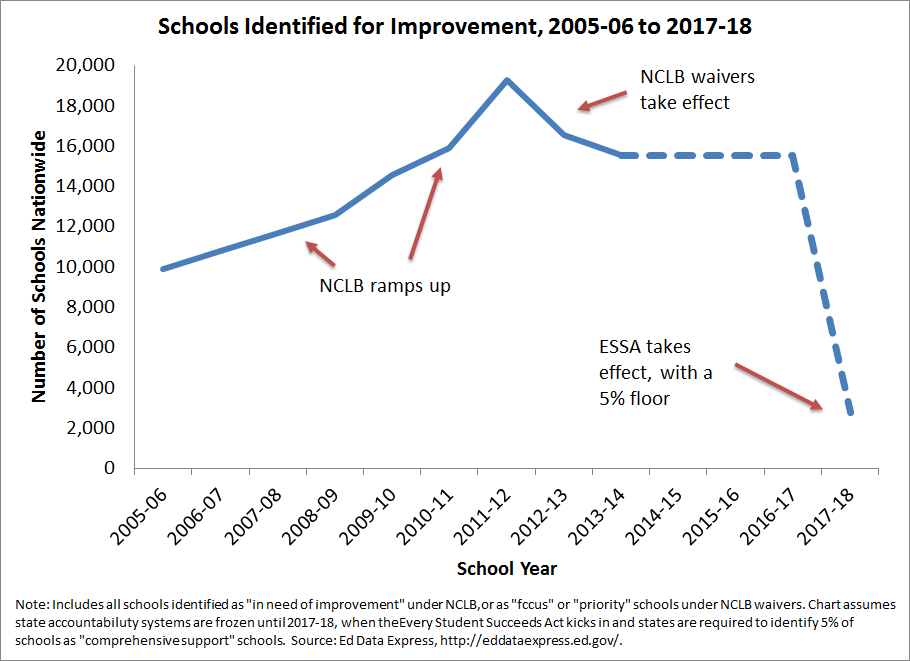

In a Washington Post op-ed over the weekend, I argued that the new education law, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), will radically diminish expectations for our nation’s public schools. I ran the numbers and found that, from NCLB’s peak until ESSA becomes fully implemented in 2017-18, about 17,000 schools will be let off the hook for student performance. We’ll shift from an expectation that all schools need to improve to an emphasis on just the worst of the worst performers.

This sets us up for a giant cliff. As NCLB ramped up expectations, more and more schools were identified for improvement. In 2011-12, we reached a peak of 19,270 schools nationwide on official “in need of improvement” lists. (Note that I’m explicitly NOT using the more commonly known “Adequate Yearly Progress” identification here, because nothing happened to schools until they failed to meet AYP for two consecutive years.) That was about 40 percent of Title I schools or 20 percent of all schools nationwide.

No one knew it then, but 2012 was the peak. The Obama Administration began granting waivers from NCLB that year, and the number of schools identified for improvement immediately began falling. It will plateau for the next couple years as states prepare for the new law, but in 2017-18 the number of schools identified for improvement will plummet all the way down to about 2,750 schools. Because not all schools receive Title I funding, that means less than 3 percent of schools nationwide will be told they need to improve.

(Click on the chart below to make it bigger.)

Pre-ESSA, these numbers varied wildly state-to-state. Some states had extremely high percentages of schools identified for improvement, while others set much lower bars. But these numbers offer the best explanation for why Washington Democratic Senator Patty Murray would champion a bill with such low expectations for schools. Murray cited it as a key reason for her support, and indeed it’s not hard to see why: Her state was on a rollercoaster ride. Out of 2,400 schools statewide, the state identified 552 schools for improvement in 2011-12. Washington received a waiver in 2012 and the number fell to just 137. But when Washington subsequently lost its waiver, it fell back onto the NCLB expectations ramp, and the number of schools identified rose all the way to 1,385 schools. It will stay at that level until ESSA is full implemented in 2017-18, when it will fall all the way down to just 46 schools (5 percent of its Title I schools).

No one knows exactly how Washington or other states will implement ESSA, and they could decide to identify far more schools than they’re required to. But based on what we saw from states under waivers, where states pretty much just met the minimum requirement, the ESSA floor will likely serve as a powerful anchoring mechanism.

Update: I’ve had several questions about whether any of this matters–do schools respond in productive ways to the threat of identification? The answer is yes, there’s evidence from North Carolina that the threat of being identified for improvement did spur schools to respond in ways that increased student learning. There’s also a broader research literature suggesting that accountability with consequences will spur greater changes than simple transparency. See pages 9-11 here for a longer discussion of this question.

December 14, 2015

The Coming ESSA Cliff

By Bellwether

Share this article

More from this topic

Meeting the Moment: How 4 Philanthropic Foundations Are Stepping Up Right Now

Teaching Interrupted: How Federal Cuts Threaten a Promising Teacher Residency Program

Does Increasing Graduation Requirements Improve Student Outcomes?

No results found.