Despite its relatively small size, the state of West Virginia has had a significant influence on national politics. Take for example West Virginia’s educators, whose two-week strike in 2018 sparked similar protests across the country.

Yet, stagnant salaries are not the only financial problem facing teachers and states: there is a growing teacher pension crisis.

Here again, West Virginia is at the center of the debate. The state reformed its pension plan in the early 1990s, but by 2005, reverted back to the statewide pension system. The West Virginia experiment is now frequently cited as a cautionary tale when other states attempt to refashion their teacher retirement systems. Critics argue that pension reform simply doesn’t work.

However, that reading of West Virginia’s pension reform is incomplete and based on commonly held myths about pensions and alternative retirement plans.

To better understand the important lessons from West Virginia’s pension reform, we analyzed the structure and modeled the wealth accumulation for each of the state’s retirement plans. In a new report, “Teacher Pension Reform: Lessons and Warnings From West Virginia,” we found that neither the state’s pension fund, nor the defined contribution (DC), 401(k)-style plan it offered in the intervening years, were particularly well-structured. And as a result, both systems failed to provide a majority of teachers with adequate retirement benefits. So the problem was not the reform: it was the design of both the pension and DC plans.

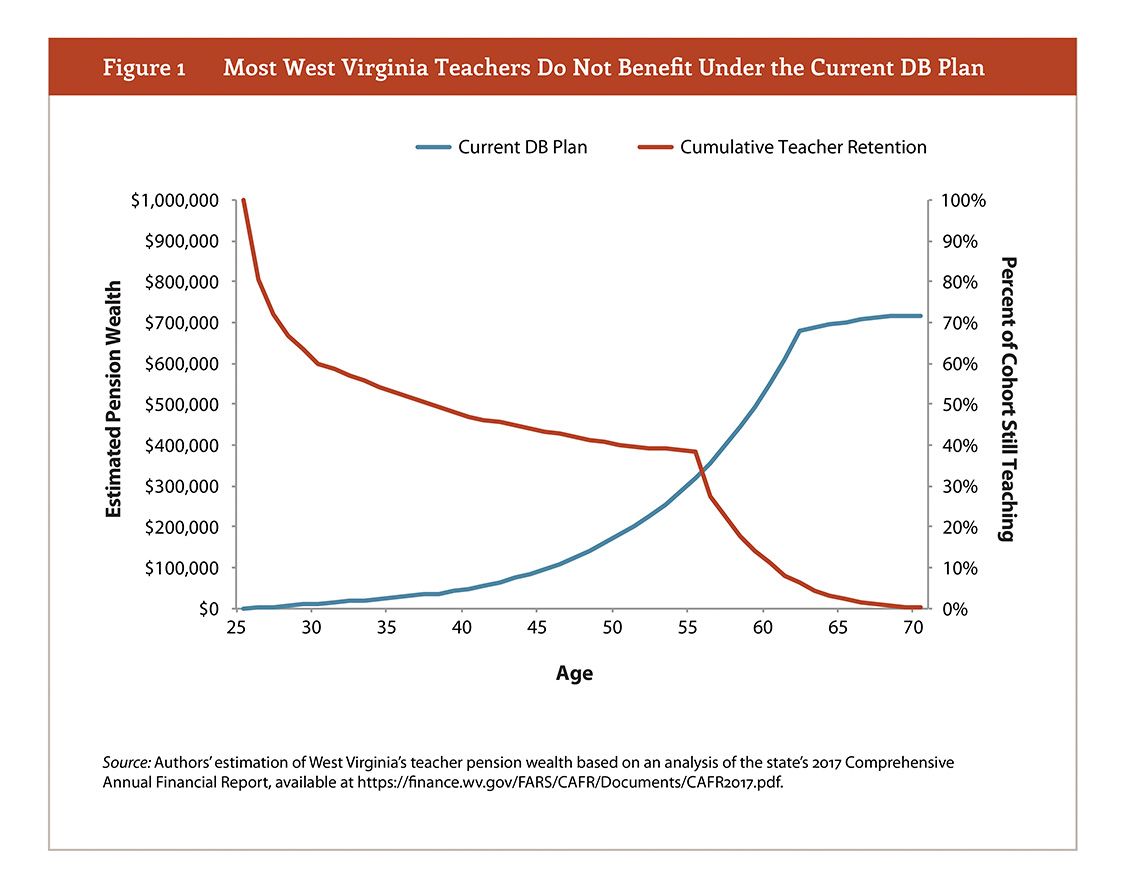

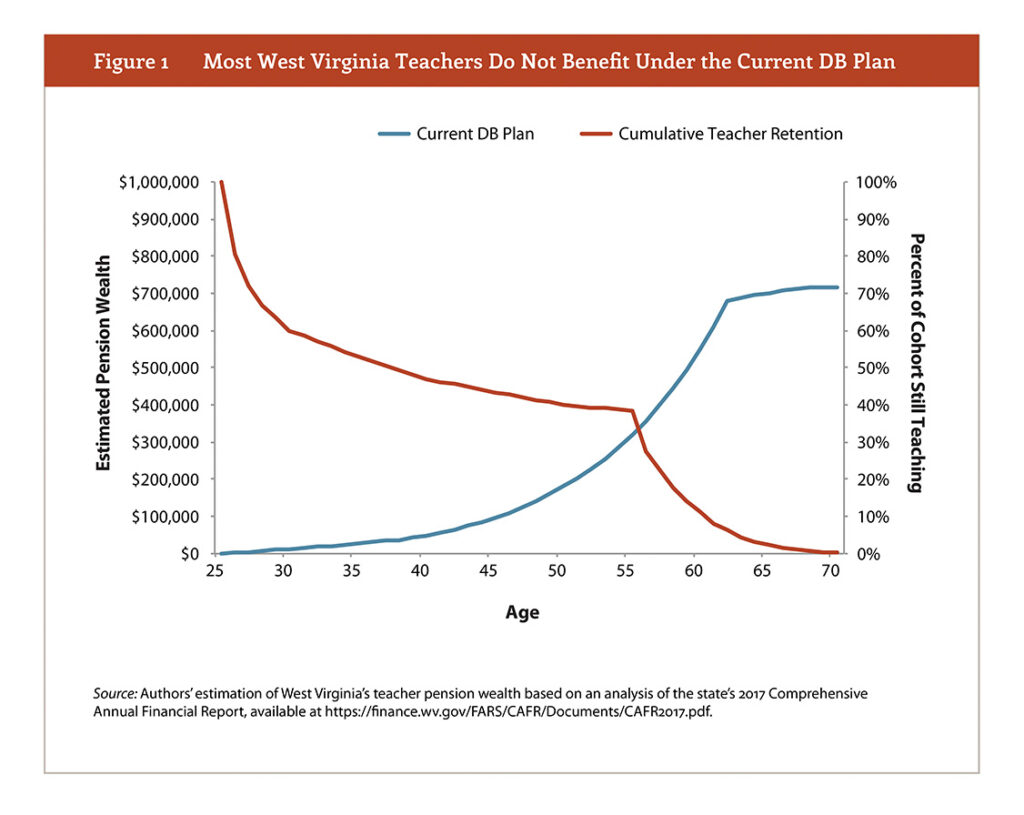

A principal problem with the West Virginia pension fund is — as with most state pension funds — that it award the most significant benefits only to those teachers who serve 25 or more years in the classroom. In and of itself, this is not necessarily bad. The issue, however, is that only about 40 percent of West Virginia educators spend 25 years working in schools. As shown in the graph below, at 55, when benefit wealth begins to accumulate more rapidly, 62 percent of teachers have already left the profession.

However, the problems with West Virginia’s pension plan should not be misunderstood as an endorsement of the state’s DC plan. It too had structural flaws. That plan required teachers to work 12 years before qualifying for full benefits. That vesting period is unusually long. Indeed, it would be illegal in the private sector under federal standards. Moreover, only about half of educators in West Virginia ever met that threshold.

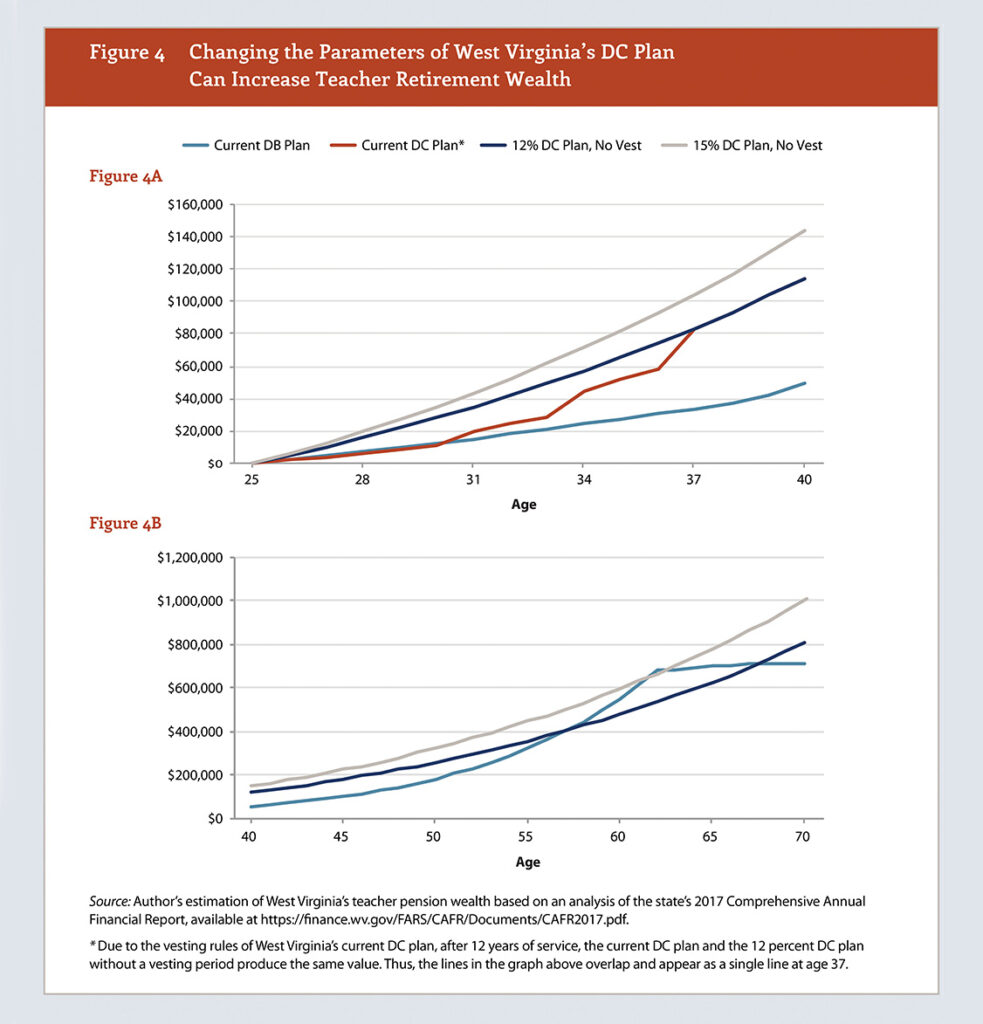

West Virginia, as well as other states, could restructure their teacher retirement plans to provide a higher quality benefit to teachers. In the graph below, I modeled out two alternative DC plan structures and compared them with West Virginia’s current pension and its DC plan. Changing vesting rules, for example, could provide a more valuable benefit to early-career teachers.

This is not to say that a statewide pension fund cannot be restructured to more effectively meet teachers’ needs. As my colleague Chad Aldeman wrote recently, there are ways to redesign pension funds to be more aligned with today’s educator workforce.

But if states elect to offer a DC plan to their teachers, they should consider the lessons offered by West Virginia’s pension reform and design plans that include the following 5 features:

- Automatically enrolls employees into the program;

- Sets the shortest possible vesting period for teachers to qualify fully for their retirement benefits;

- Establishes employer and employee contribution rates that, at minimum, total between 10 and 15 percent;

- Provides low-cost options and life cycle funds that adjust an employee’s portfolio as she gets closer to retirement; and,

- Creates an actionable and accountable plan to pay down unfunded liabilities.

Pensions are not inherently better for teachers. Neither are DC plans. In both cases, structure matters. Policy choices matter. As states think through how best to confront the growing pension crisis, they should consider the missteps West Virginia made and carefully construct retirement plans that meet the needs of teachers and taxpayers.

As pension costs continue to skyrocket, states need to base their decisions on a careful analysis of how their systems affect educators’ retirement wealth and impact taxpayers. They cannot afford to be unduly influenced by misunderstandings of past reforms.