This post was written by a past Bellwether intern. Read more about our internship program here.

Growing up, I went to a relatively diverse high school, with over 60% of the student population being students of color and a third of those being Asian American or Pacific Islander (AAPI). Although there was a large Asian-American population, most of them were middle- to upper-middle class and either South or East Asian — there was no Pacific Islander representation.

For most of my K-12 education, I fully subscribed to the myth of AAPIs as a “model minority,” assuming we were all high-achieving in both school and work and financially stable. There seemed to be an unspoken rule amongst my Asian friends to take the highest possible class, whether AP or honors, for each subject, and if you didn’t do that, people looked down on you. In this environment, I lumped together all AAPIs and perceived over 30 different ethnic groups as homogenous.

When looking at AAPIs as a whole, they do in fact academically outperform whites. On average, they have higher test scores and grades, are more likely to graduate high school and college, and get into more selective schools compared to White Americans and other racial groups. However, some AAPI subgroups are not performing well in school and need more resources in order to succeed.

I didn’t realize that there are ethnic groups under the AAPI umbrella who are not graduating college, let alone high school, and that many of these ethnicities are also much more likely to be impoverished than AAPIs as a whole (according to the U.S. Census). I didn’t realize that as a Vietnamese American with two college-educated parents, one with an advanced degree, I am the exception not the rule. According to Pew Research, in 2015, only 25% of foreign-born Vietnamese Americans over the age of 25 had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

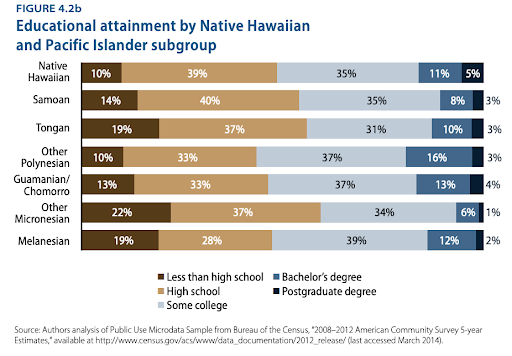

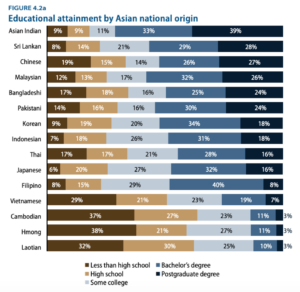

There are over 30 different ethnic groups that fall under the label of Asian American and Pacific Islander, and the “model minority” myth fails to take into account the ethnic and class differences amongst AAPIs. Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders, on average, attain less education compared to East Asians. The Center for American Progress reports that while 49 percent of Asian Americans in 2012 had a bachelor’s degree or higher, fewer than 15% of Hmong, Cambodians, and Laotians and only 19% on average of Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Furthermore, over 30% of Hmong, Cambodian, and Laotian adults over 25 do not have a high school diploma or equivalent.

In addition to discrepancies in education attainment, there is also a wide distribution of wealth among AAPIs. Although AAPIs, on average, had a higher median household income in 2015 than the nation’s median income ($73,060 versus $53,600), this masks that Bangladeshi Americans’ median household income was $49,800, Nepalese Americans’ median household income was $43,500, and Burmese Americans’ median household income was $36,000. Pacific Islanders are more likely to live in poverty compared to Asian Americans, with 20.4% of Pacific Islanders in 2012 living in poverty compared to 12.8% of Asian Americans.

Given the statistics, it is clear we need better data disaggregation so that leaders and educators can understand the different experiences of AAPI ethnic groups and identify which groups may need more support. In order for policymakers and educators to change the status quo, they need data-backed evidence of the existing achievement and income gaps.

Several years ago, the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC) launched a national campaign called All Students Count to push government agencies at all levels to collect and report disaggregated AAPI data. More recent efforts have centered on state and local governments. For example, California, Minnesota, and Washington all recently passed data disaggregation bills and Massachusetts and New York are currently trying to pass similar ones.

As the fastest growing racial group in America, AAPIs deserve more targeted interventions, especially given that the income gap between AAPI ethnic groups continues to grow. In fact, in 2016, AAPIs had the largest income inequality out of all racial groups. This open letter from educators and leaders offers more information on data disaggregation efforts and addresses common misconceptions. I strongly believe that data disaggregation will lead to more educational equity amongst all AAPIs.

This post is by former Bellwether intern Truc Vo. Read more about Truc here.