Amid recent fuss about the accuracy of the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights Data Collection, it’s important to look at how those data errors can meaningfully impact education experiences for young people for whom no other substantive national research exists: students attending school in secure juvenile justice facilities.

Approximately 50,000 young people are incarcerated in juvenile justice facilities across the country on any given day, and they are supposed to attend school while they are in custody. For many of these students, attending school in a secure facility is the first time they have engaged with school consistently in three to five years. Their school experience while in custody is their last best chance to change the trajectory of their lives.

The problem is we know very little about the quality of these educational opportunities.

The biannual data collection conducted by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is intended to be a comprehensive survey of education access in all schools in the country, and it now includes these juvenile justice schools. But our analysis from earlier this year found that states, and OCR at large, have not taken the responsibility for accurate reporting seriously. In fact, inconsistencies and incompleteness render the OCR data nearly meaningless. Alarmingly, the data still do not allow us to answer even the simplest question: How many students were enrolled in a juvenile justice school in 2013-14?

Some states, like Arkansas and South Carolina, dramatically underreported enrollment in their juvenile justice schools: data suggesting fewer than ten students (and as low as zero) were sufficient to stop us in our tracks. There is no reasonable explanation for this. We know that Arkansas and South Carolina must have more students attending school in juvenile justice facilities but somehow, they were not counted as enrolled.

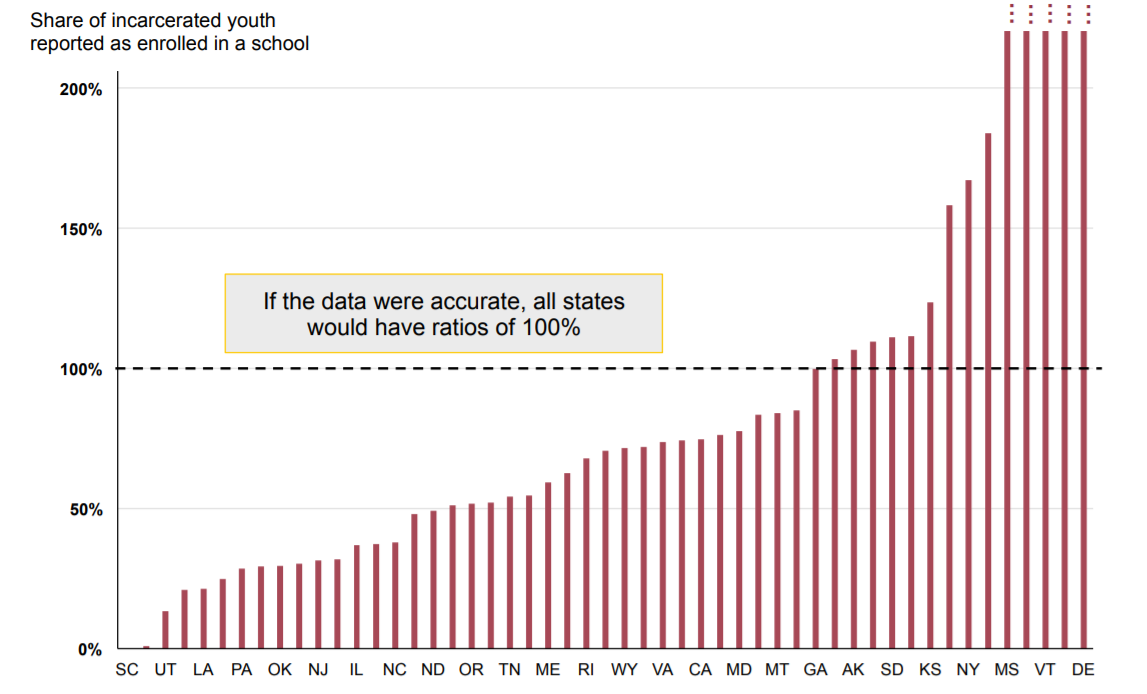

In order to corroborate the data from OCR, we cross-referenced with another data set: the residential facility census conducted by the Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). We looked at the annual “headcount” data provided by OJJDP and attempted to line that up with the school enrollment data reported to OCR. In all ordinary cases, those two numbers should be close to equal since all states require school attendance for youth who are incarcerated. But in most states, the number of students recorded as incarcerated and the number of students attending juvenile justice schools were not even close.

It turns out that many schools also overreported enrollment, the most extreme being Delaware, where student enrollment was 940% of residential headcount. There are a number of possible innocuous reasons for this miscount, the two most likely being misclassification of schools (neighborhood schools are incorrectly marked as juvenile justice schools) or disparate count types (one-day snapshot vs. total served over the year). But regardless of the source of the mistake, it means that the data are invalid.

When we excluded states that wildly over- or underreported school enrollment (by more than 30% on either end), we were left with only 18 states where the two data sets were more or less in alignment. We went on to conduct an analysis on the data from those 18 states to draw conclusions about student access to coursework. (You can see our results in the full report here.)

One important purpose of longitudinal data collections, like the OCR civil rights data collection, is to show trends over time. Because this first data set is so messy, it cannot effectively serve as a baseline for comparison to future years.

The next round of data were recently released by OCR, and we will update our findings to include the 2015-16 data. But there is no indication that data collection procedures or expectations have improved over the prior data set.

In stark contrast to the sophisticated data that we have become accustomed to having at our fingertips for our neighborhood schools, this OCR data is the only standardized information that we have about juvenile justice schools across the country, and it is insufficient to answer even the most basic questions about equal education opportunity. Without major improvements to the accuracy and completeness of the data being collected by OCR, the schools serving some of our country’s most vulnerable and chronically disengaged students will remain unknowns with little hope for improvement.