In my previous post, I talked about the importance of rigorous research and the need for researchers to engage directly with education stakeholders. Yet some educators remain skeptical about the value of partnering with researchers, even if the research is relevant and rigorous. Why might education agencies fail to see the value of conducting rigorous research in their own settings?

For one thing, letting a researcher into the nitty gritty of your outcomes or practices might reveal that something isn’t working. And since it’s rare that educators/practitioners and researchers are even in the same room, education agency staff may be concerned about how findings will be framed once publicized. If they don’t even know one another, how can we expect researchers and educators to overcome their lack of trust and work together effectively?

For one thing, letting a researcher into the nitty gritty of your outcomes or practices might reveal that something isn’t working. And since it’s rare that educators/practitioners and researchers are even in the same room, education agency staff may be concerned about how findings will be framed once publicized. If they don’t even know one another, how can we expect researchers and educators to overcome their lack of trust and work together effectively?

Furthermore, engaging with researchers takes time and a shift in focus for staff in educational agencies, who are often stretched to capacity with compliance and accountability work. Additionally, education stakeholders may have strong preferences for certain programs or policies, and thus fail to see the importance of assessing whether these are truly yielding measurable improvements in outcomes. Finally, staff at educational agencies may need to devote time to help researchers translate findings, since researchers are not accustomed to creating summaries of research that are accessible to a broad audience.

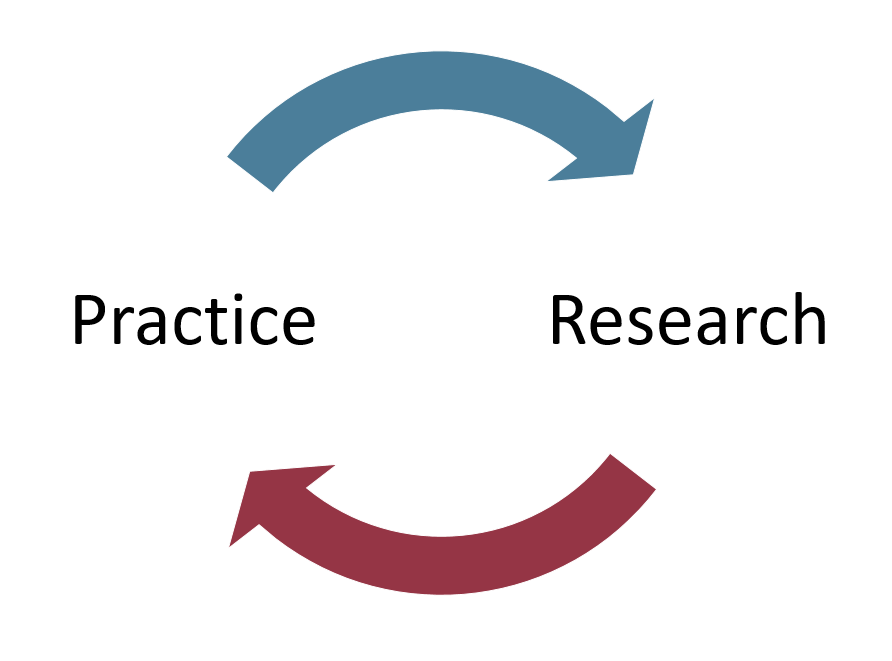

Given all this, why am I still optimistic about connecting research, practice, and policy?

First, educational agencies have a lot of data that can be used to answer important questions and improve educational systems for all students. (This abundance of data is due, in part, to federal investments. Since its establishment with the Education Technical Assistance Act of 2002, the State Longitudinal Data Systems grant program has awarded more than $700 million in competitive grants to help states make informed decisions to improve student learning and outcomes.)

More importantly: we are starting to see the benefits of researchers working with staff in educational agencies. A growing body of research has stemmed from partnerships with school districts or state education agencies. These team efforts have made use of existing data to yield policy-relevant research findings, which have, in turn, helped education agencies improve teacher hiring and selection, identify stronger candidates to mentor novice teachers, or understand the impact of career and technical education.

Further funding to support meetings between educators and researchers would be valuable. As Carrie Conaway noted in her presidential address at the 2019 Association for Education Finance and Policy (AEFP) meeting (I serve on AEFP’s board), relationships between practitioners and researchers are the key to making sure research actually gets used in service of students. In-person discussions about research findings can strengthen these relationships.

Among the promising examples of partnerships that support relationship-building is the Strategic Data Project (SDP) fellowship (I’m an alumna), which has been placing data strategists in education agencies since 2008. SDP’s data fellows have partnered on studies that evaluate the impact of math coursework acceleration and interventions to prevent attrition from the college pipeline. As Mathematica has noted, embedding fellows within education agencies can help education leaders see the value of using data to inform decisions. Yet even at agencies eager to embrace data-informed decision-making, many agency staff may not know how to interpret research findings or draw inferences to improve policy and practice. We need to invest as much in developing the skills of potential research consumers as we do in research producers.

My previous post began with a series of questions: What characteristics of teacher candidates predict whether they’ll do well in the classroom? Do students benefit from accelerated math coursework? What does educational research tell us about the effects of homework? Existing partnerships have given us rigorous evidence on the first two questions and research resources for the third. Progress in education is only possible if we’re willing to use the data we’ve collected to answer the questions that education stakeholders actually have, and if education leaders are able to interpret and use that research to improve programs and policies.

Acknowledgement: Carrie Conaway provided helpful feedback on an earlier outline of this post.