Today, it’s become popular to extol the benefits of equity and to talk about virtually everything a school or district does as an equity activity. But in a world where almost everything is equity, how can we know if our individual efforts are working?

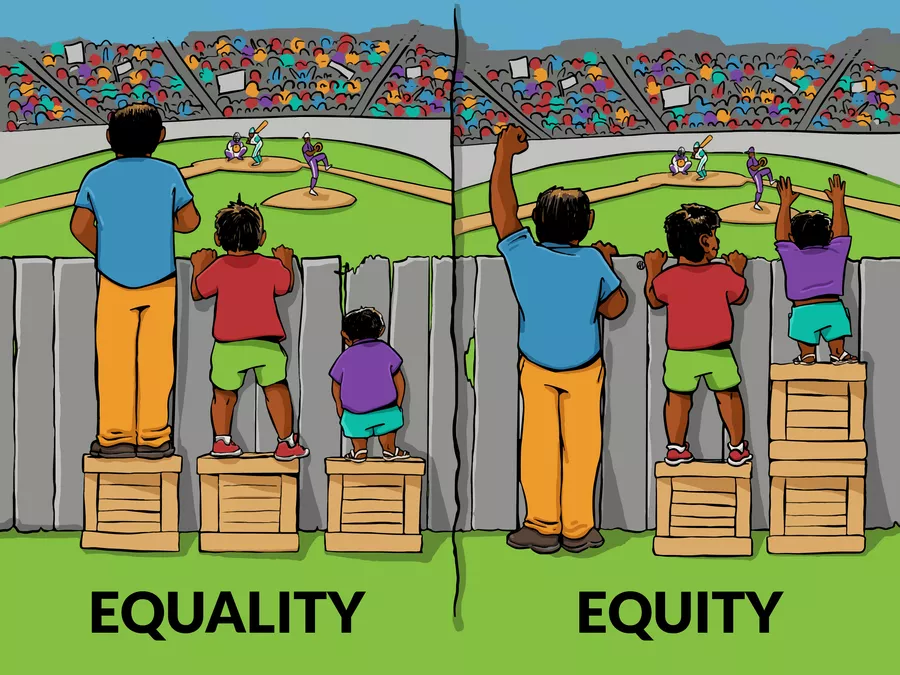

Let’s begin by considering the definition of equity in its broadest sense–often defined in contrast with equality. Whereas equality means that everyone gets the same thing, equity means that everyone gets what they need.

In practical terms, equality might mean that every student has access to high quality curriculum, but equity might mean that every student has access to a high quality curriculum that also matches their experiences and calls upon examples to which they can relate. An equality paradigm isn’t necessarily bad or wrong, but it only gets us part of the way to helping every student realize his or her potential.

In practical terms, equality might mean that every student has access to high quality curriculum, but equity might mean that every student has access to a high quality curriculum that also matches their experiences and calls upon examples to which they can relate. An equality paradigm isn’t necessarily bad or wrong, but it only gets us part of the way to helping every student realize his or her potential.

Today’s schools are far more diverse than they were fifty years ago in the sense that more students from around the world — and more students who used to go to schools across town — are now learning together in the very same buildings. But schools have also long been places where highly unique individuals come together to learn what they need to pursue academic and life pathways that are a fit with their goals and abilities. We do not expect every second grade student to become a plumber or a computer scientist, so why would we design an education system that narrows their opportunities instead of expanding them as broadly as possible?

In many ways, broadening opportunities is exactly what we’re doing. We’re working to personalize learning and create individualized experiences that resonate with, engage, and excite students. But for some students, we’re too often overlooking critical opportunities to provide them with what they need. In particular, students of color and students from immigrant backgrounds, as well as students with intellectual and emotional challenges, rarely see people like them in key roles in the education system.

Across the United States, people of color compose just four percent of district executives – superintendents and other senior system leaders. And for women of color, this percentage plummets.

The stark absence of educators and leaders of color and other minority groups sends the message that education is something that is really designed for a mainstream that includes mainly White and middle class people. Not for students who possess great potential but whose demography doesn’t match that of their teachers and leaders. But we need our schools to reflect the demographics of our community so that all students, regardless of background, get the clear and profound message that “people like them” can and do succeed.

While we work to ensure that all students have meaningful and productive learning experiences that help to build a pipeline of future educators, though, we can also do more to help students build the key skills they need to be successful in class beginning immediately. That’s what we at AVID had focused our energy and attention on for the last nearly forty years: helping teachers build the skills to teach student the strategies that can make them better learners.

Adversity visits all of us in different ways. Some students face disadvantages in the form of limited resources, perhaps including few adults to nurture and support them. In many schools, adults want to provide the support students need, but the best ways to do that are not always self-evident. AVID partners with those teachers to provide programming and training on how to help students learn to do things like take effective notes, use those notes to study, and check their own learning. As pedagogy evolves, our programs do, too. We partner with educators in diverse settings across the U.S. to regularly review and update our training so that it matches with all forms of teaching and learning — and with the changing worlds that children experience outside of school.

Whether you adopt AVID or develop the skills to support equity in a different way, we encourage you to attend not just to whether all of your students are getting access to high quality materials and teaching, but to ensure that all of your students are getting what they need.

Dr. Edward Lee Vargas began working with AVID in 2016. Prior to AVID, he was a school administrator in California, New Mexico, Texas and Washington where he received recognitions such as State Superintendent of the Year in California (2006) and Washington (2014). He is known for developing innovative approaches in diverse communities leading to improvement of test scores and graduation rates and increasing family and community engagement.