Yesterday we talked about the honesty gap analysis that was released in Virginia.

A lot of response. One that caught my eye was a truly remarkable article in The Washington Post that instead of reporting the scope of the analysis Virginia released more or less just took it on. And essentially made the case that who cares about proficient, basic is good enough! Almost half of kids proficient is actually really great – at least relatively. And didn’t engage with the rampant racial, ethnic, and income achievement gaps the report laid out or the information about how the state has systematically changed its accountability system to make things look better over time.

It’s particularly startling when you juxtapose it against this Washington Post editorial from just a few years ago on the same issue:

Mr. Northam’s comments are part of an unfortunate trend in Virginia to pull back from rigor in assessments and accountability. Instead of adopting the muscular requirements of Common Core and its assessments, the state has stuck with assessments seen to be among the easiest in the nation. Some critical tests, such as the fifth-grade writing SOL, were recently jettisoned. And now state education officials are in the final stages of adopting regulations that would overhaul how schools are accredited. The board would widen a loophole to allow for “locally awarded verified credits” from the local school board in lieu of exam passage. Officials argue there is the need to broaden the lens by which schools are judged. We agree that student growth and closing the achievement gap should be recognized, but the proposal tilts too far toward letting schools off the hook for their failures. The emphasis appears to be not on actually improving schools but rather on approving how they appear.

Does democracy die in darkness or not? The news article, which reads like an editorial, says no. The actual editorial page says yes. Readers say, wtf?

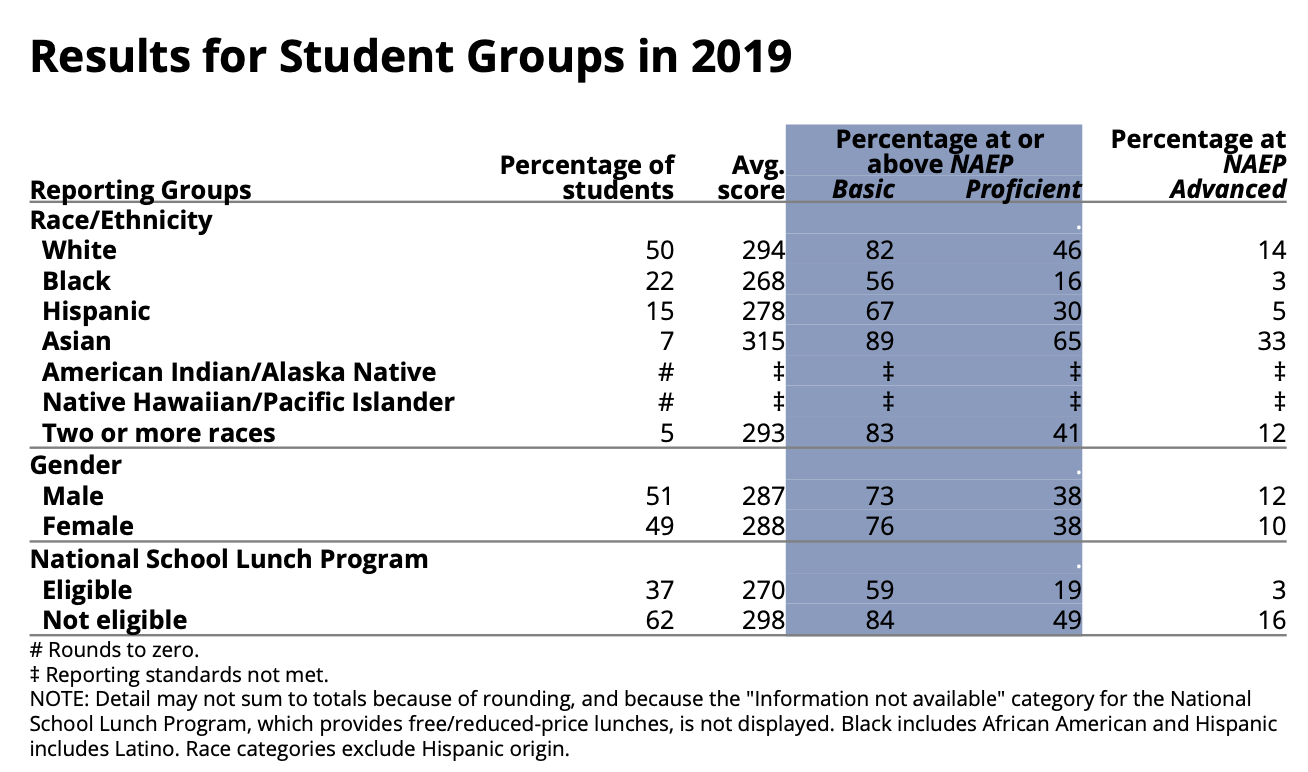

Here’s a snapshot on Virginia, from federal data courtesy of NAGB, if you think these 8th-grade math and reading outcomes are good enough then, yes, you should oppose this. If not, let’s see if there is a bipartisan center for a meaningful school improvement package touching on the various dimensions of this problem from finance, to accountability and support, and yes hopefully more choices for families.

Elliot Regenstein (who has a new book coming!) reached out about early education and its lack of prominence in the report. His note is brief but covers a lot of ground. I asked him if I could publish his feedback, he graciously agreed:

The new Our Commitment to Virginians report makes some very important points about student proficiency in the Commonwealth – both the need to improve overall proficiency, and to think differently about how proficiency rates are developed and talked about. The Youngkin Administration is to be commended for expressing a commitment to improving student outcomes. As the conversation continues, it will be important for Virginia to wrestle with an important question: when kids are not proficient in middle school and high school, how did they get there?

Pre-pandemic, Virginia’s data told a pretty clear story:

-Many kids were falling behind even before kindergarten started. Data on kindergarten readiness showed that roughly two of every five entering kindergartners were “not ready.”

-Schools were not able to catch kids up when they were behind. In fact, 93% of students in Virginia attended schools in districts where – in the aggregate – students were losing ground over time on the state’s proficiency benchmarks. (Virginia’s data is unusual in this regard, and that may be related to the “honesty gap” identified in the new report; having very inclusive standards for proficiency may make it harder to show growth.)

This data suggests that there must be two prongs to any strategy for improving proficiency in Virginia. One is to work with schools to help them improve student growth, and in turn proficiency; regardless of how the state defines proficiency, there’s clearly a need to help schools improve (as there is in every state). But the other is to improve kindergarten.

While Virginia’s recent governors have been strong supporters of early learning, historically Virginia has been a laggard when it comes to state early childhood funding. Pre-pandemic its state-funded preschool program served a lower percentage of children than any of the states it borders, with lower-per-pupil spending. But the state has been working diligently to improve early childhood outcomes, including a strong focus on improving the quality of teacher-child interactions. That work is really important for children in the first five years of life, and probably also offers some important lessons for the state’s K-12 system. If Virginia is serious about a long-term strategy to improve student outcomes, the pre-kindergarten years are a critical opportunity that must be addressed.