Last week Harrisonburg, Virginia caught a lawsuit over its policy on transgender and gender questioning students. There are similar lawsuits pending elsewhere.

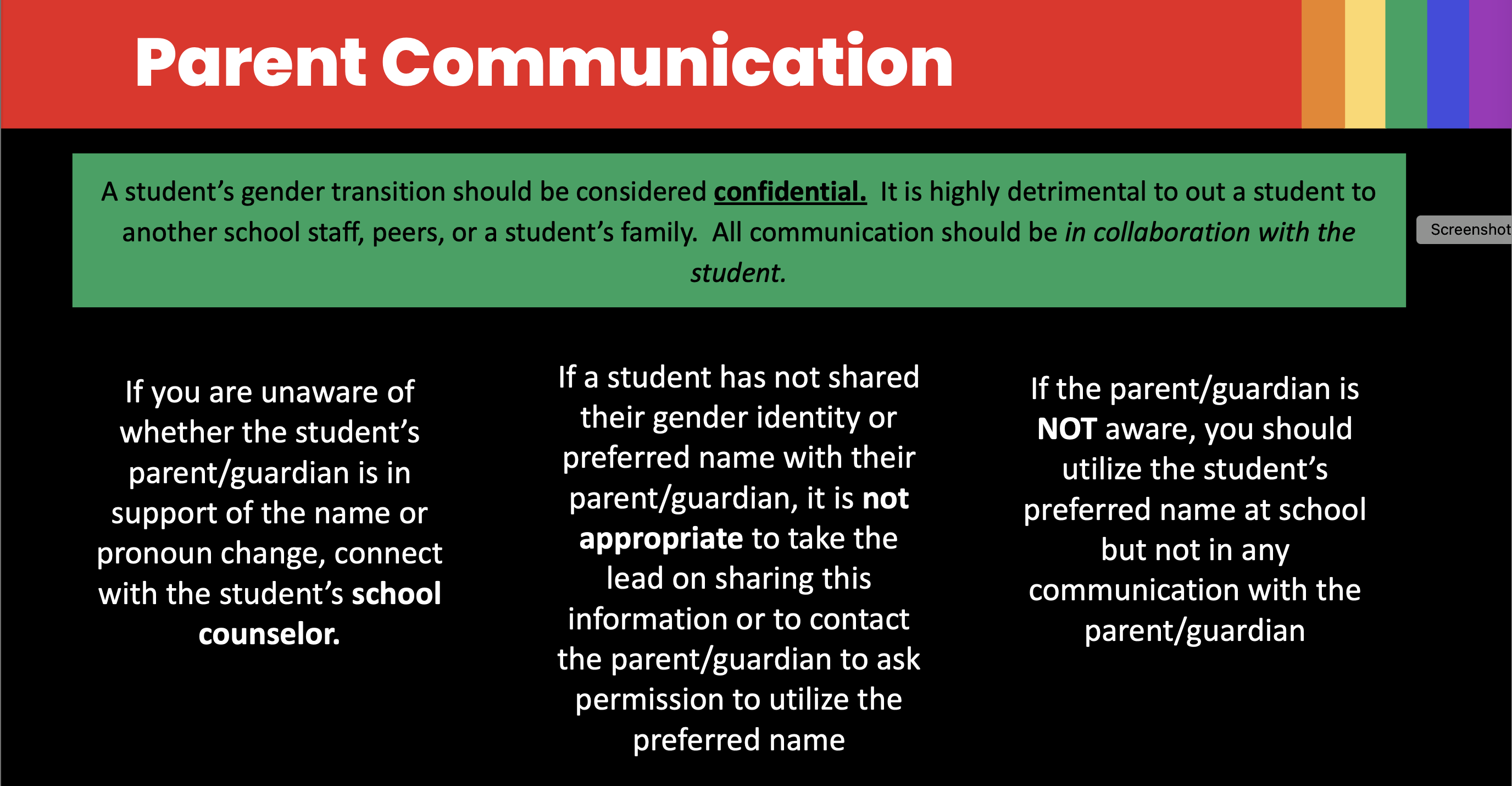

There are a bunch of issues, but the crux one is language like this:

When you scratch beneath the surface more and more people believe, thankfully, that public schools should be welcoming and inclusive places for all students and teachers in terms of how they choose to identify and live their lives. And while there is going to be litigation, I suspect that courts will affirm that schools can require teachers and other personnel to call students by their preferred name or pronouns.

As we’ve discussed around here, in a public educational setting you have diminished free speech rights and teach a defined curriculum and course of study. In other words, the state can compel or restrict certain speech in a way that would not be permissible elsewhere. Names and pronouns probably fall under that. It’s also good manners, which is no small thing. (I suspect that some of what’s happening now in the name of being gender affirming is not going to age well but also in two decades people will look back and be like ‘you all really argued that much about pronouns?’)

But where the line lies when it comes to keeping information from parents is much more fraught. People tend to say, well, you can’t tell a parent something that might cause harm to a child. But, because it’s a real issue in some cases, there are provisions about that issue in state laws, including these current crop of parents’ rights bills. Here’s sample language from Florida:

This subparagraph does not prohibit a school district from adopting procedures that permit school personnel to withhold such information from a parent if a reasonably prudent person would believe that disclosure would result in abuse, abandonment, or neglect, as those terms are defined in s. 39.01.

So in practice, that’s not the issue here. The issue really turns on when is it appropriate for school personnel to just withhold information because they think they have that prerogative, know better, or whatever and when safety is not an issue? This is the more common use case. A lot of people say ‘never.’ Some say ‘sometimes.’ And some do say ‘a lot’ because schools and educators do know better. Seeming to adhere to that latter sentiment sure didn’t help Democrats in the 2021 governor’s race in Virginia. Among parents, surprise(!), ‘never’ is the prevailing position.

A bill is moving through the legislature in North Carolina that will thrust this issue back into the discourse. Along with, again, what gender and sexuality content should be taught to kindergarten to grade 3 students and some other related issues, at issue is this language:

Some sort of mandatory reporting of any question a student might ask seems heavy handed and at odds with the informal work of schools and the professional judgement of teachers. But seeming to side with the idea that schools should encourage kids to conceal things from their parents seems like a political trap – and a problematic policy? A lot of Democrats seem to privately get this, ‘but the groups’ they say in explaining how out of position Democrats are on this issue and how “in loco parentis” has rapidly evolved to “tu es parentis” – which again is a bad way to win elections in a country with a lot of parents.

It doesn’t seem unreasonable that a school and a teacher should call a kid what they want to be called – though parents don’t support that as much as you might think (and like many issues geography matters a lot). That doesn’t seem like a free speech or free exercise issue in a public educational context even though it triggers groups on the right. But, at the same time, it also seems like the, you know, parents should get a say, too?

This is roughly where most Americans live or can get to. It is not where loud activists, on all sides, live.

Meanwhile, around the country there have been a series of walk backs like this one in New Jersey:

“Unfortunately, our learning standards have been intentionally misrepresented by some politicians seeking to divide and score political points,” Murphy said in a statement. “At the same time, we have seen a handful of sample lesson plans being circulated that have not been adopted in our school districts and do not accurately reflect the spirit of the standards. Any proposed educational content that is not age-appropriate should be immediately revised by local officials.”

And also, conversely, some schools are leaning into this – here’s KIPP:

I realized I was doing an injustice to not only my students but to myself by ignoring the complexities of intersectionality- a word my 5-year-old students understand very well.

They know this fancy word means that we are a beautiful bouquet of flowers. Each flower is different yet important. One flower is pretty all by itself but a whole bunch of them? That’s special and beautiful.

The way I walk through this world as a person of color cannot be talked about unless I include my cis male queer identity. If this is what I truly believe, shouldn’t I take this approach with my students? The big question, and probably the hardest to answer, is how?

KIPP’s a choice school. Choice does help with these questions to some extent. I’m supportive of school choice for a few reasons most notably empowerment, but I don’t think a society can just choice its way out of hard social questions.

Instead, it seems two ideas are worth considering:

First, as with other controversial issues the key is curriculum not leaving everyone to their own devices. The DIY approach here is rocket fuel for social media driven outrage.

Second, maybe this is all too important and fraught to leave to the loud activists on all sides? I was reading about this proposed transgender athlete sports bill in Ohio and it seems like neither the proponents or the opponents get what the law actually would require. Harrisonburg is being sued for things that go beyond a state policy on this issue and will likely spark more calls for a state policy curtailing them like North Carolina’s proposed bill.

Instead, perhaps it’s like this:

If you’re the kind of person for whom having a picture of a teacher with their same gender significant other, their family, or that kind of thing really triggers you then perhaps the public schools are not the right place for you or your family. Likewise, if you’re the kind of person who thinks it’s just essential that kids in K-3 get instruction in gender and sexuality the public schools might not be the place for you, either.*

The public square demands an always evolving balancing of freedom and compromise. So this would leave the rest of us to sort out the messy balancing act here between life’s public and private realms and rights, freedom, and inclusion.

*The polling on this is mixed (and selectively cited by advocates) but seems very sensitive to question wording. Vague questions find support for teaching gender and sexuality in elementary school. If you ask about K-3 and the specific language in the recent Florida legislation, the results are quite different.