Block Grants

A Framework for States’ Response to Potential Flexibility in Federal K-12 Education Funds

Note: This memo reflects federal policy developments through March 17, 2025. Bellwether will continue monitoring the Trump administration’s actions on federal education funding and update this as necessary.

Summary

The Trump administration may push for a shift away from the current formula-driven federal K-12 education funding toward more flexible block grants — part of a broader effort to significantly scale back the U.S. Department of Education and direct more education policy decision-making to the states.1 If Congress authorizes this new flexibility, state leaders and policymakers must be prepared to use it wisely in service of students and schools.

The concept of block granting could be straightforward from a federal accounting perspective but would present new challenges and opportunities for state policymakers. While it would not likely provide states with more overall federal funding, block granting could give states much more flexibility on how they spend their funding. The degree of that flexibility, however, is an open question.

This memo anticipates key policy questions and options state policymakers will need to consider if Congress converts federal education funding to block grants — with a focus on ensuring that federal funds continue to target support to marginalized students (e.g., multilingual students, students with disabilities, students from low-income families). It is not an endorsement of this funding approach, nor does it try to predict exactly how Congress will implement it.

If state policymakers are granted broad authority to allocate federal education funding, they must ensure that those dollars continue to target supports for marginalized students. This memo explores how different allocation choices could give states more or less control over the use of funds but does not dig deeply into the details of how states could use that control to drive K-12 programmatic decisions at the local level. Readers should not interpret the choice to focus on questions of allocation first as an implication that the use of funds is less important. In fact, if states do get substantial flexibility to direct both the allocation and use of funds, there is real opportunity for states to better allocate funding to benefit students and real risk that funding is diverted in ways that harm students who most need the supports these funds currently provide.

If the Trump administration and Congress shift major federal K-12 funding programs to block grants, key considerations for state policymakers will include:

- Determining options for distributing block-granted funds and weighing their costs and benefits, such as:

- Maintaining current federal formulas at the state level.

- Integrating block grants into existing state funding formulas.

- Developing new formulas based on priority student needs.

- Aligning funding mechanisms with student needs, focusing particularly on marginalized students.

- Providing sufficient guidance and guardrails on the use of funds to maximize efficacy and protect students in the absence of federal requirements.

- Addressing oversight mechanisms to balance flexibility with accountability.

Types of Federal Grants

Discretionary Grants: Funding appropriated to executive branch agencies through legislation with broad authority for agencies to administer grants to third parties.

Formula-Driven Grants: Funding that includes statutory language on how it should be distributed to grantees along with requirements for how funding can be used.

Block Grants: Funding that is distributed to states by statute with minimal constraints on how that funding can be deployed to achieve a specific outcome.

Federal Education Aid: Formula-Driven Versus Block-Granted

The largest pots of federal funding for K-12 school districts are formula-driven grants, with specifics about their allocation and use directed by foundational laws like the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The largest federal formula grants target students from low-income families and students with disabilities — but these funds also come with statutory and regulatory requirements on how states and local schools can allocate and spend funds. Proponents of this more regulated approach to federal education funding argue that it is the best way to improve outcomes for the student groups those funding streams are intended to support.2 Critics argue it does not account for the varying needs of different communities and that “block granting” federal funding would allow states and districts to better align spending with local educational needs and priorities.3 Federal K-12 education block grants could take many forms, but they ultimately would distribute more funding to states with fewer requirements for how funds are allocated within states and reduced federal spending and reporting requirements.

While the Trump administration has signaled support for block-granting of federal education funding,4 the idea dates back nearly half a century. Soon after the U.S. Department of Education was established in October 1979, Republican presidential candidates and some policy analysts and advocates called for shuttering the agency and moving federal funding support for school systems to block grants. Block grants were also part of the Heritage Foundation’s 1981 “Mandate for Leadership” — widely considered to be the policy blueprint for the Reagan administration. The most recent incarnation of this proposal is detailed in another Heritage Foundation publication, “Project 2025,” which echoes a decades-long call for the elimination of the U.S. Department of Education by moving aid programs to other agencies and then block-granting that funding to states.5

Under a more flexible block grant structure, the federal government could loosen restrictions on how K-12 funds are allocated, how funds are used, or both. Completely removing all restrictions is likely to face political headwinds, particularly if changes are made in a way that creates winners and losers financially or if federal lawmakers wish to retain some control over the use of funds.

Both sets of decisions are important — how dollars are allocated at the state and local levels and how those dollars are used to improve student outcomes — particularly given that federal dollars intentionally target resources to marginalized student groups (e.g., multilingual students, students with disabilities, students from low-income families). That is precisely why states should approach any newfound flexibility on funding decisions judiciously.

How could the block-granting of K-12 education funding happen?

Moving federal education funding distributions from current formulas to block grants will require federal legislation.

The timing of this potential change is unclear, as is its scope. For example, it is unclear whether the Trump administration would include both IDEA funding and funding authorized through the Every Student Succeeds Act, the most recent reauthorization of ESEA. Other, smaller federal grant programs could be folded into this effort, but this memo focuses on the largest federal K-12 funding programs.

Even if substantial federal K-12 funding is converted to block grants, a federal role in governing those funds will remain. Block grants still require a formula to divide funding among and potentially within states. There could be some guardrails on how federal education dollars can be spent, but the scope of those requirements — including accountability measures that are regarded as a civil rights issue by many — is an open question.

Options for State Policymakers to Distribute K-12 Block Grants

If states have carte blanche to allocate federal funds according to their priorities, how might they do so? As of the publication of this memo, there is no concrete proposal for block-granting federal education funding. But given the administration’s apparent desire to move in this direction, state policymakers should be ready to adapt quickly. This memo offers policy considerations grounded in two assumptions about what could be true if block-granting happens:

- Similar funding levels: Block grants would provide similar total funding to states compared to amounts received in fiscal year (FY) 2024, less expiring COVID-19 pandemic-related funding. While Project 2025’s education policy prescriptions call for a phase-out of ESEA Title I, Part A funding — the largest source of federal K-12 education funding — over a decade (which would require federal legislation),6 this memo assumes flat funding.

- “No strings attached:” States would have wide latitude to deploy block-granted funding as they see fit, both in terms of how funds are allocated to schools and how funds are used. This would require state policymakers to translate their new flexibility to local contexts. While the potential conversion of federal K-12 education funding to block grants would likely include some guardrails on the use of and accountability for those dollars, the scope of those measures is unknown at this point. As such, this memo assumes minimal federal constraints on how states could deploy block grants.

Three State Approaches to Managing Block Grants

Priorities in ESEA and IDEA — such as funding to support students from low-income families, students with disabilities, and others — should remain priorities for state policymakers, even with less prescriptive federal requirements. Most states already direct their own K-12 resources and support to the same student groups and priorities (though in widely varying ways).

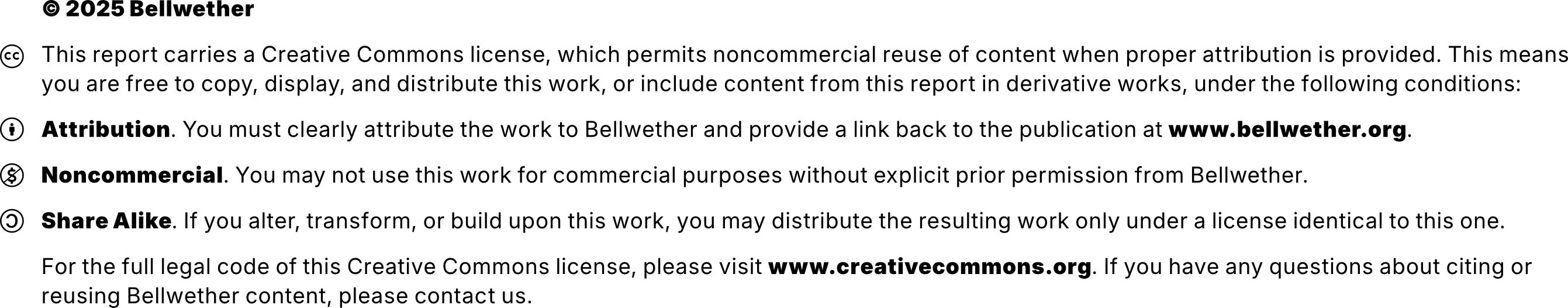

State policymakers can think in terms of three broad approaches to allocating block-granted federal education funding — each of which offers advantages and drawbacks — that would maintain these underlying commitments (Table 1). States will likely need to combine two or all three of these approaches, since any one option is unlikely to adequately meet the range of student needs addressed by current federal policy. (See “State Formulas as a Mechanism to Support Priorities via Block Grants” for how states can use existing state student-weighted funding formulas to allocate federal funds.)

One critical consideration for state policymakers if they choose to change how federal funds are allocated is the extent to which those changes would create “winners” and “losers” at the local level. These are not new funds. Changes to the method for allocating funds to local K-12 school systems may better align funding with student needs overall, but shifts in the amount of funding allocated to individual school systems will impact the level of service and support currently being provided to students. Policymakers should assess the impact of changes at the local level to determine the wisdom and feasibility of big shifts in funding allocations while prioritizing the needs of students. Phasing in changes over time could allow states to gradually move toward strategic realignment of funding allocations while minimizing abrupt shifts in funding at the local level.

State policymakers should also avoid replacing state or local dollars with federal dollars. While it is unclear whether current requirements that federal education dollars “supplement, not supplant” state and local funds would persist in a block grant scenario, simply swapping out federal funds for state dollars would substantially reduce the overall investment in education. States may also need to establish their own “supplement, not supplant” or “maintenance of effort” policies to prevent local entities with sufficient local tax resources from simply replacing discretionary local dollars with federal funds and reducing supports for students.

State Formulas as a Mechanism to Support Priorities via Block Grants

Every state has a K-12 formula (or set of formulas) that distributes state education funding. These formulas play a major role in school finance — nearly half of all K-12 education revenue comes from states. In contrast, federal grants are a relatively small but meaningful part of K-12 funding, typically accounting for less than $1 of every $10 allotted for K-12 public schools (excluding one-time relief funding as was offered to schools during the Great Recession and the pandemic).7 Most states (39) and the District of Columbia already distribute the lion’s share of K-12 funding through weighted student formulas (WSFs) or a hybrid model that includes a WSF, which provides more funding to support specific student and/or community needs (poverty and special education-related needs typically generate the most targeted funding in these hybrid models).8 States that do not use WSFs often have separate categorical formulas that are structured to address specific student needs by supporting a limited range of uses.

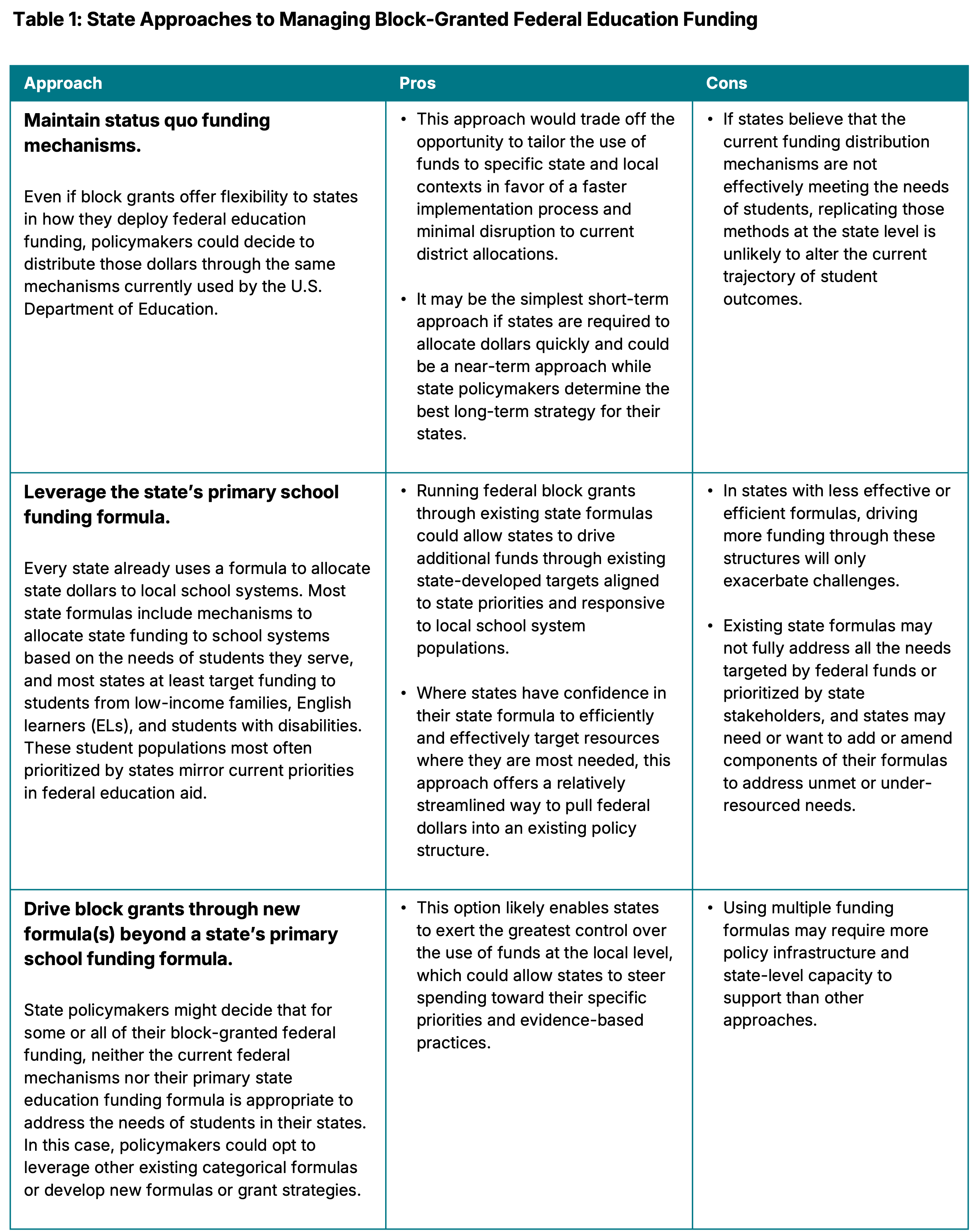

If the federal government converts its funding to block grants, states could consider using existing state funding formula mechanisms, such as weights or categorical funding streams, to direct block-granted federal education aid. For example, weights for poverty and concentrated poverty could help direct dollars that would have otherwise been allocated by the formula for ESEA Title I, Part A. Special education weights could be used to direct funding from IDEA, Part B (Table 2).

For example, Tennessee’s state formula, the Tennessee Investment in Student Achievement (TISA), provides an additional 25% in funding for each low-income student enrolled and another 5% on top of that in districts where 35% or more students are low-income (Disclosure).9 Under a block-grant scenario, Tennessee could choose to use its Title I funds to increase the percentage of either or both of those funding weights, which would increase the amount of funding per low-income student and/or funding for districts and charter schools serving the highest concentrations of low-income students. Although that strategy focuses on the same populations of students as current Title I allocations, the formula is not the same. Shifting Title I allocations to the TISA methodology would change the amount flowing to individual schools and school systems, and state policymakers would need to consider the impact of those changes at the local level.

Weighted Student Funding Terms

Base Amount: A dollar amount that is used to represent the cost of educating a student.

Weight: A percentage used to represent the additional cost associated with serving a particular student need that is multiplied by the base amount to calculate targeted funding for that need. For example, a 20% weight for student poverty in a state with a $10,000 base would generate $2,000 per pupil for each student from a low-income family.

For more information on how WSF operates, refer to Bellwether’s Splitting the Bill series of school finance issue briefs.

Not all federal funding streams have direct analogs in state school funding formulas. For example, ESEA Title II funding is used to improve educator quality — a function not explicitly addressed in state school funding formulas. In those cases, directing some of the newly converted block-granted funds through an increased base student amount in a state’s WSF might be appropriate.10 Currently, 20% of ESEA Title II, Part A funding is distributed based on total student population, while the remaining 80% is allocated based on student poverty. A state considering folding block-granted federal funding into its WSF might, therefore, consider using a portion of what would have been its ESEA Title II, Part A grant to increase the base amount in its funding formula. Since most state WSFs apply percentage weights stemming from specific student needs to the base amount, base increases naturally increase funding associated with weighted student groups (because percentage weights will apply to a higher base amount). In states without a WSF, an alternative would be to convert federal funding into a standalone categorical grant.

To the extent that existing state school funding formulas reflect states’ funding priorities and focus on marginalized students, allocating federal block grants through state formulas could be a relatively straightforward way to ensure that block-granted funds conform to state priorities without requiring policymakers to create entirely new allocation methodologies. However, states will need to both attend to changes in allocations that result from distributing federal funds through state formulas and ensure that federal funds do not replace state or local funds and reduce overall educational investment.

State policymakers should also consider factors beyond allocation mechanisms. Federal education funding comes with directives for how those dollars should fit into the larger school funding landscape within states (e.g., the “supplement, not supplant” rule in ESEA’s and IDEA’s “maintenance of effort” requirement for special education spending). How should those current requirements shape state policymakers’ approach to block-granted federal education aid?24

States that use WSFs typically allow substantial flexibility in spending decisions at the local level. As a result, if states leverage their formulas to allocate federal block grants, absent additional federal or state guidance, local K-12 school systems would have that same flexibility with federal dollars. Conversely, state categorical funding programs for specific student needs often have data collection and reporting requirements that constrain how those dollars are used.25 If states rely on their own formulas to navigate block granting, they may want to reassess the level of flexibility districts have with those funds. State leaders should consider whether to provide additional guidance or strategic direction on federal block grant funds, either to comply with any federal requirements or to assert more state control over local spending decisions.

Conclusion: Key Questions and Next Steps

Block-granting federal K-12 education funding to states would place even more responsibility on state policymakers to develop and implement effective education funding policies. Initial analysis of pandemic relief funding via Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief grants indicates that absent thoughtful targeting of funds to marginalized student groups, additional funding may not translate to improvements in student outcomes.26 To maximize the potential that block-granted federal education funds can have on improving student outcomes, state policymakers should consider the following set of strategic questions.

Scope potential policy options for allocating funds:

- What federal requirements remain or are newly created to govern block grants, and what allocation options are allowable as a result?

- How would different approaches to distributing block-granted federal funding affect districts’ funding and current services and supports for students? Which of those scenarios best aligns with state education priorities and strategies for improving student outcomes?

- What are the costs and benefits of phasing in a new approach to allocating federal funds?

- What state statutes need to be updated to support the distribution and spending of block-granted federal aid?

Develop options for effective implementation:

- How will states guide and support LEAs to effectively leverage new flexibilities to improve student

outcomes and maintain focus on marginalized students? - What existing requirements for the use of funds under federal law — such as “supplement, not supplant,” “maintenance of effort,” or programmatic requirements — might states want to replicate?

- How will district and state reporting requirements change with a new system for distributing block-granted federal aid?

- How will states assess the impact of their implementation strategy? What additional accountability and/or transparency measures might states want to include to assess impact?

- What will states need to do to ensure compliance with federal requirements?

A shift from formula-driven federal K-12 education funding to block grants would create new opportunities and responsibilities for state leaders and policymakers to ensure that federal education dollars are deployed in ways that best support students and schools. Before any federal proposals on this front are implemented, state leaders and policymakers should consider the policy options at their disposal along with their second-order effects to ensure that block-granted funding provides the greatest possible benefit to students with the greatest learning needs.

Endnotes

- Cory Turner, “Trump Prepares Order Dismantling the Education Department,” NPR, March 6, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/03/05/nx-s1-5316227/trump-order-dismantling-education-department.

- Natasha Ushomirsky and David Williams, “Likely Effects of Portability on Districts’ Title I Allocations,” The Education Trust, February 2015, https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Likely_Effects_of_Portability_on_Districts_Title_I_Allocations_020915.pdf.

- Lindsey M. Burke, “Chapter 11: Department of Education,” 2025 Presidential Transition Project, 2025, https://static.project2025.org/2025_MandateForLeadership_CHAPTER-11.pdf.

- Chad Aldeman, “Should Trump Be Taken Literally or Seriously on Closing Education Department?,” The 74, February 27, 2025, https://www.the74million.org/article/should-trump-be-taken-literally-or-seriously-on-closing-education-department/.

- Burke, “Chapter 11: Department of Education.”

- Ibid.

- Alex Spurrier, Bonnie O’Keefe, and Jennifer O’Neal Schiess, “How Are Public Schools Funded?,” Splitting the Bill no. 2, Bellwether, updated October 2023, https://bellwether.org/publications/splitting-the-bill/.

- Linea Harding, Carrie Hahnel, and Bonnie O’Keefe, “Equity-Driven State K-12 Funding,” Bellwether, January 2025, https://bellwether.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Equity_Driven_State_K-12_Funding_Bellwether_January_2025.pdf.

- “Tennessee Investment in Student Achievement Guide,” 2024-25 school year, Tennessee Department of Education, 2025, https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/tisa-resources/2024-25_TISA_Guide.pdf.

- Linea Koehler and Bonnie O’Keefe, “How Does the Base Amount Work in Student-Based Funding Formulas?,” Splitting the Bill no. 10, Bellwether, October 2023, https://bellwether.org/publications/splitting-the-bill/.

- Fiscal Year 2024 Congressional Action budget, Department of Education, https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/about/overview/budget/budget24/24action.pdf.

- Rebecca R. Skinner and Isobel Sorenson, “ESEA Title I-A Formulas: A Primer,” Congressional Research Service, September 19, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47702.

- “Supplemental Funding for Low-Income Students: 50-State Survey,”

ExcelinEd, 2023, https://excelined.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ExcelinEd_EdFunding_LowIncomeFundingComparison_PolicyReport.pdf. - “K-12 Funding 2024: Funding for Students From Low-Income Backgrounds,” 50-State Comparison, Education Commission of the States, March 2024, https://reports.ecs.org/comparisons/k-12-funding-2024-06.

- Internal Bellwether analysis.

- Donna Perlmutter, Jennifer Sable, Erika Kessler, Evan Linett, Richa Arora, Tabitha Tezil, Sara Alhassani, Cong Ye, Jiayi Li, Daniel Bruce, Charles Blankenship, Jie Sun, and Teerachat Techapaisarnjaroenkij, “State and District Use of Title II, Part A Funds in 2023-24,” U.S. Department of Education, 2025, https://www.ed.gov/media/document/state-and-district-use-of-title-ii-part-funds-2023-24-109457.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, amended through P.L. 118-159 (2024), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-748/pdf/COMPS-748.pdf.

- Indira Dammu, Bonnie O’Keefe, and Jennifer O’Neal Schiess, “How Can School Finance Systems Support Students With Additional Learning Needs?,” Splitting the Bill no. 5, Bellwether, updated October 2023, https://bellwether.org/publications/splitting-the-bill/; Miss. H.B. 4130 (2024), Mississippi First blog, May 20, 2024, https://www.mississippifirst.org/blog/2024-house-bill-4130/.

- “Title IV, Part A: Student Support and Academic Enrichment Program Profile,” T4PA Center, U.S. Department of Education, 2020, https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/2020/09/Title-IV-A-Program-Profile.pdf.

- “Student Support and Academic Enrichment (SSAE) Grants,” Congressional Research Service, updated May 4, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10910/4.

- Krista Kaput and Jennifer O’Neal Schiess, “What Are the Core Funding Components of Part B, Grants to States (Section 611) Funding in the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)?,” Splitting the Bill no.18, Bellwether, May 2024, https://bellwether.org/publications/splitting-the-bill/.

- Krista Kaput and Jennifer O’Neal Schiess, “How do School Finance Systems Support Students With Disabilities?,” Splitting the Bill no. 16, Bellwether, May 2024, https://bellwether.org/publications/splitting-the-bill/.

- Rebecca R. Skinner, “The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as Amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA): A Primer,” Congressional Research Service, February 12, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45977; “The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B: Key Statutory and Regulatory Provisions,” U.S. Department of Education, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41833.

- Harding, Carrie Hahnel, and Bonnie O’Keefe, “Equity-Driven State K-12 Funding.”

- Kevin Mahnken, “Research: Learning Recovery Has Stalled, Despite Billions in Pandemic Aid,” The 74, February 11, 2025, https://www.the74million.org/article/new-scorecard-release-shows-stalled-growth-weak-returns-on-federal-aid/.

Acknowledgments, About the Authors, About Bellwether

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our Bellwether colleagues Andrew J. Rotherham, Andy Jacob, and Bonnie O’Keefe for their input and Dwan Dube for her support. Thank you to Amy Ribock, Kate Neifeld, Zoe Cuddy, Julie Nguyen, Mandy Berman, and Amber Walker for shepherding and disseminating this work, and to Super Copy Editors.

The contributions of these individuals and entities significantly enhanced our work; however, any errors in fact or analysis remain the responsibility of the authors.

Disclosure

Bellwether works with organizations and leaders who share our viewpoint-diverse commitment to improving education for all young people — regardless of identity, circumstance, or background. As part of our commitment to transparency, a list of Bellwether clients and funders since our founding in 2010 is publicly available on our website. An organization’s name appearing on our list of clients and funders does not imply any endorsement of or by Bellwether.

Separate from the creation of this memo, Bellwether provided advice and assistance to the Tennessee State Board of Education related to the performance-based public hearing process allowed under the Tennessee Investment in Student Achievement (TISA) Act. Bellwether also served as a technical adviser to the Tennessee Department of Education in 2022, providing data modeling support to the department during legislative deliberations that led to TISA.

About the Authors

Alex Spurrier

Biko McMillan

Jennifer O’Neal Schiess

Bellwether is a national nonprofit that exists to transform education to ensure systemically marginalized young people achieve outcomes that lead to fulfilling lives and flourishing communities. Founded in 2010, we work hand in hand with education leaders and organizations to accelerate their impact, inform and influence policy and program design, and share what we learn along the way. For more, visit bellwether.org.