Federal Policy on Students Experiencing Homelessness

Early Action for States in Response to Recent Changes

Summary

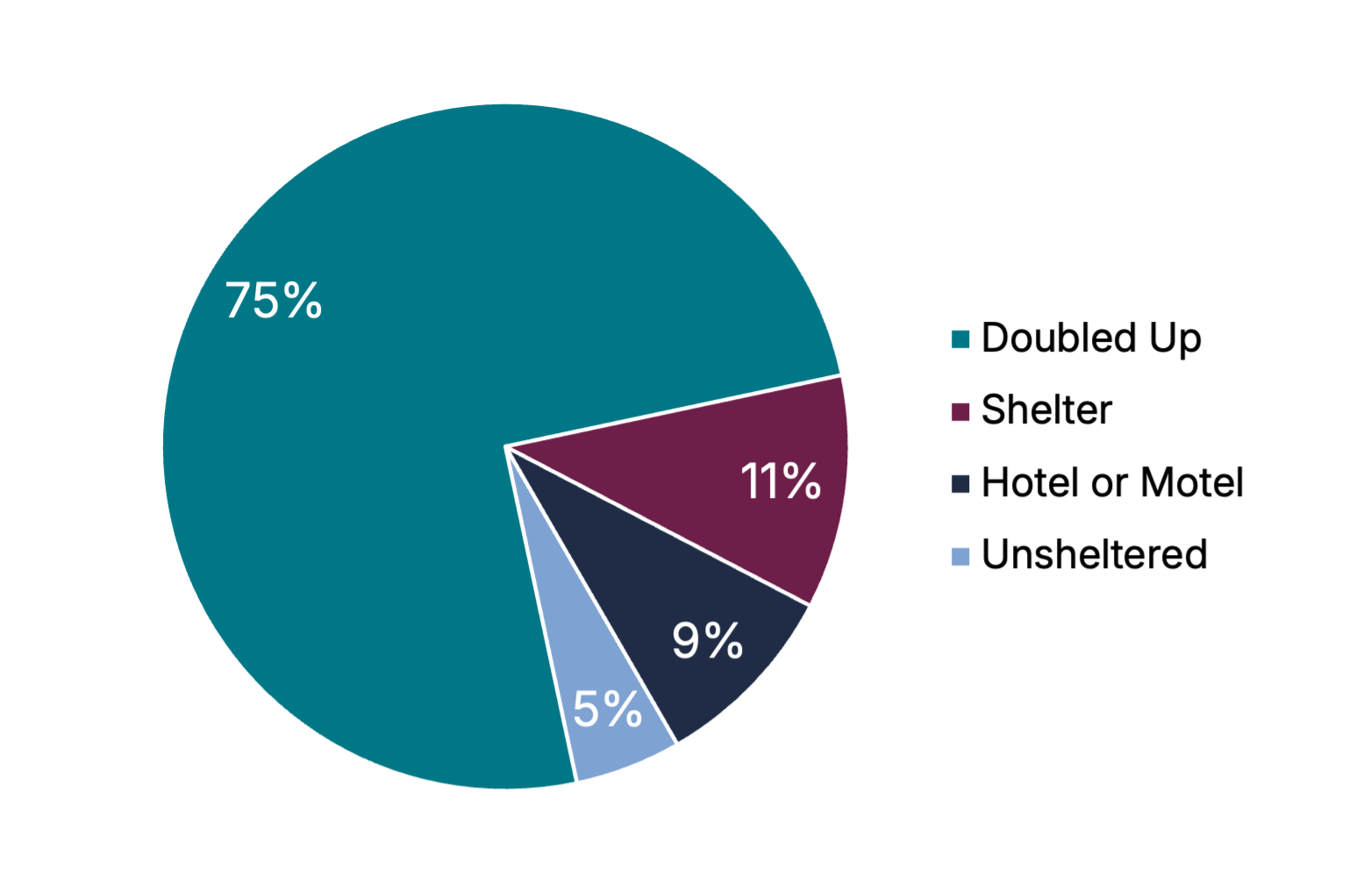

As of the 2022-23 school year (SY), approximately 1.37 million pre-K through Grade 12 students in the United States — nearly 3% of the total pre-K through Grade 12 population — were identified as experiencing homelessness. The majority of these young people, approximately 75%, were “doubled up,” living temporarily with others due to loss of housing or economic hardship. Another 11% were staying in a shelter, 9% were staying in a hotel or motel, and nearly 5% were unsheltered (Figure).

Figure: Living Arrangements of Students Experiencing Homelessness

Homelessness affects a diverse range of young people across America. Forty percent of children and youth experiencing homelessness are Hispanic/Latino, 26% are Black or African American, and 25% are white; 12% percent live in rural communities, 20% receive special education services, and 9% are unaccompanied; and as many as 29% of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ+, compared to 16% of all students.

Students experiencing homelessness often face far greater academic, social, emotional, and basic needs challenges than their peers with stable housing. The unpredictability of their living situations can result in frequent school absences and midyear transfers, disrupting both learning and continuity. In SY22-23, nearly half of students experiencing homelessness were chronically absent, missing 10% or more of school days.

Housing instability, often coupled with poverty, also increases the risk of food insecurity and makes it more difficult for students to access essential health care. Those experiencing homelessness face a higher likelihood of engaging in substance use and risky sexual behavior, are more likely to experience suicidal thoughts or attempts, and are more frequently exposed to violence compared to their stably housed peers. For example, homeless youth are up to 10 times more likely to become pregnant or get someone pregnant, and students who have experienced pregnancy are themselves 10 times more likely to experience homelessness.

Ultimately, these intersecting challenges create significant barriers to learning, with students experiencing homelessness consistently scoring lower in reading, math, and science compared to their stably housed peers.

The student homeless population is particularly vulnerable, demanding targeted support from local, state, and federal governments. Amid ongoing federal uncertainty, it is more important than ever for state and local leaders to step up and ensure that students experiencing homelessness receive the stability, resources, and educational opportunities they deserve.

This memo outlines key policy changes that will impact students experiencing homelessness and options state policymakers should prioritize to support them, including:

- Engaging in the federal policy conversation and sharing local impact.

- Codifying protections for homeless students in state law.

- Establishing or increasing state-level funding for homeless students.

- Maintaining and publicly reporting data on student homelessness.

- Creating mechanisms to facilitate or enhance cross-agency collaboration and coordination to support students experiencing homelessness.

- Investing in professional development for school-based staff around best practices for serving students experiencing homelessness.

- Strengthening the capacity of state homeless coordinators and local liaisons.

Terminology: Federal Definitions of “Homeless” Vary Across Agencies.

The primary federal legislation governing education for children and youth experiencing homelessness is the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (McKinney-Vento). This legislation defines “homeless children and youth” as individuals who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, including those who are sharing the housing of others (“doubled up”); whose primary nighttime residence is a public or private place that is not designed to be a regular sleeping accommodation; who are living in cars, parks, public places, abandoned buildings, substandard housing, bus or train stations, or other similar settings; and migratory children who are living in these circumstances. “Unaccompanied youth” are children or youth meeting the McKinney-Vento definition of homeless and who are not in the physical custody of a parent or guardian.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Higher Education Act, Head Start Act, Child Nutrition Act, and the Violence Against Women Act all use the McKinney-Vento definition of “homeless children and youth” to qualify young people for their programs.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has four categories of homeless: 1) literally homeless, 2) imminent risk of homelessness, 3) homeless under other federal statutes, and 4) fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence. HUD‘s definition of “literally homeless“ includes individuals and families who lack “a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.” However, this definition does not include people who are ”doubled up” as defined by McKinney-Vento. Furthermore, to be eligible for HUD programming and services under category three (homeless under other federal statutes), HUD requires those individuals and families to be both experiencing persistent housing instability and be expected to continue to experience housing instability for “an extended period of time.” As a result, most HUD programming does not serve those who are homeless under other federal statutes such as McKinney-Vento.

The varying federal definitions of homeless result in differing counts of homeless children and youth among agencies as well as differential access to the programs and services those agencies operate.

Federal Role in Homeless Students’ Education and Changes Under the Trump Administration

Passed by Congress in 1987 and most recently reauthorized in 2015 by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), McKinney-Vento is the primary federal legislation providing educational rights and services to children and youth in grades pre-K through Grade 12 who are experiencing homelessness. The purpose of the law is to remove any “laws, regulations, practices, or policies that may act as a barrier to the enrollment, attendance, or success in school” of students experiencing homelessness. Under the law, homeless students have the right to immediately enroll in school without required records, to stay in their original school if it is in their best interest, to receive transportation to and from that school, and to access support for academic success.

McKinney-Vento established the Education for Homeless Children and Youths (EHCY) Program, administered by the U.S. Department of Education, to provide support and services to students experiencing homelessness. EHCY provides formula funding to states in proportion to their Title I, Part A, funding, and states must subgrant at least 75% of EHCY funds to local education agencies (LEAs) through a competitive grant process. EHCY also requires states to establish an office of coordinator for education of homeless children and youth to collect and analyze data on student homelessness and coordinate with state and local agencies to support students experiencing homelessness. LEAs must designate a staff member to be a local liaison who is tasked with identifying, supporting, and coordinating services for homeless students.

Through EHCY and the U.S. Department of Education’s collaboration with other agencies serving homeless children and youth — primarily the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and HUD — the federal government has long provided considerable support to young people experiencing homelessness through funding, coordination and technical assistance, research, and monitoring and oversight (Tables 1-4).

Funding

The U.S. Department of Education, HUD, and HHS have a variety of funding streams and grant opportunities that provide critical funds to states and communities to develop programs to meet the needs of young people experiencing homelessness. These federal funding streams are crucial, given that only four states have allocated state-level funding sources for homeless children and youth.

Table 1: Federal Funding Streams That Support Students Experiencing Homelessness

Historical Federal Role |

Changes Under Trump Administration |

|---|---|

| HUD’s Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG)

This is a formula grant to states and larger cities/counties that funds rapid rehousing, prevention, and other emergency programming for adults, families with children, and unaccompanied youth. |

On March 15, 2025, President Trump signed into law a year-long continuing resolution (CR) to fund the government through September 30, 2025. This CR maintained a funding level of $290 million for ESGs. However, on May 2, 2025, the administration released its ”skinny” budget request for fiscal year (FY) 2026, which includes $532 million in cuts to HUD‘s homeless programs. |

| HUD’s Continuum of Care (CoC) Program

This competitive grant program supports communities to plan and coordinate a comprehensive system to address homelessness. |

While the March 2025 CR maintained $3.54 million for the CoC program, the FY26 budget request proposed consolidating the CoC Program into ESG alongside cuts of $532 million. The proposed consolidation would likely eliminate critical CoC activities. |

| HUD’s Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program

This competitive grant program supports communities to develop a coordinated approach to end youth homelessness. |

The March 2025 CR maintained $107 million for the Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program. Though this program was not named specifically in the administration’s FY26 budget request, it would likely be impacted by the proposed $532 million in cuts to HUD’s homeless programming. |

| U.S. Department of Education’s EHCY Program

This program details the rights that homeless students have, including remaining in their school of origin; immediate enrollment; free transportation; and access to programming such as preschool, special education services, and nutrition services. It also provides grants to states and districts to help identify and serve students experiencing homelessness. |

The Department’s FY26 budget proposal eliminates EHCY funds entirely, consolidating the program and 17 other federal education grant programs into a single block grant. Under this proposal, EHCY activities would no longer be required — meaning that many homeless students would lose the rights, supports, and services currently provided through EHCY. |

| Title I, Part A (Title IA)

Title I, Part A of ESEA, which was reauthorized in 2015 by ESSA, requires all LEAs receiving Title IA funds to set aside a portion of funds to serve students experiencing homelessness. |

As of June 2025, the U.S. Department of Education has been silent on whether it intends to pursue changes to ESEA. The administration’s FY26 budget request included $4.5 billion in cuts to “streamline programs” in K-12 schools; however, it indicates the administration will preserve full funding for Title I. The Department’s FY26 budget request maintains the current level of Title I spending. |

| The American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act-Homeless Children and Youth (HCY)

This federal COVID-19 stimulus funding provided $800 million to support SEAs and LEAs in identifying and supporting homeless children and youth. An independent federal study found that these funds effectively helped states identify and serve homeless children and youth, leading to decreases in chronic absenteeism and improvements in academic proficiency. |

This was a one-time infusion of dollars to address the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on students experiencing homelessness. Funds had to be spent by January 30, 2025. The U.S. Department of Education had previously approved extended liquidation requests, allowing states to continue to spend ARP funds beyond the January 30, 2025 deadline. However, in March 2025, the Trump administration abruptly halted extended liquidation payments for ARP funds, including HCY. |

| Runaway and Homeless Youth Program

Authorized by the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act of 1974 and operated by the Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) at the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), a division of HHS, this program provides grants to communities to support street outreach and community programs (e.g., transitional living, maternity group homes). |

In April 2025, HHS fired more than 10,000 employees, including more than 500 employees from ACF program offices. This downsizing is likely to impact the continuity of programming and services for vulnerable populations — including those served by the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program. |

| Head Start

Head Start, operated by ACF, provides early learning, development, health, and family well-being programming for young children ages birth through five. Children experiencing homelessness are automatically eligible for Head Start programs. |

Trump’s May 2025 budget request did not include any cuts to Head Start. However, substantial downsizing at HHS, including at ACF, is likely to impact the continuity of programming and services like Head Start. |

Coordination and Technical Assistance

Students experiencing homelessness face a range of needs that stem from inadequate or unstable housing, including food insecurity, limited access to health care, exposure to violence, mental health needs, substance abuse, early and unwanted parenthood, and lower academic achievement. These wide-ranging needs are addressed through programs operated out of multiple federal agencies. Because of this complexity, the federal government plays an important role in both coordinating among agencies and providing support services to agencies to ensure that students can access the programs and services they need.

Table 2: Federal Coordination Efforts and Technical Assistance Related to Students Experiencing Homelessness

Historical Federal Role |

Changes Under Trump Administration |

|---|---|

| National Center for Homeless Education (NCHE)

NCHE is the U.S. Department of Education’s technical assistance center for EHCY. It provides training, materials, and other resources for state homeless coordinators and local homeless liaisons; shares research and best practices; and reports national homeless education data. |

As of June 18, 2025, the contract for NCHE is still in place. However, it is unlikely that this contract will continue if EHCY is eliminated via consolidation into a block grant. |

| ACF’s FYSB and Children’s Bureau

ACF’s Children’s Bureau oversees child welfare services including child protective services, foster care, and adoption. ACF’s FYSB oversees the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program, described above. Combined, these two bureaus provide oversight and connection across child welfare issues, including the intersection of foster care and youth homelessness. |

As noted above, in April 2025, HHS fired more than 10,000 employees, including more than 500 employees from ACF program offices. This downsizing is likely to impact the continuity of programming and services for the vulnerable populations served by ACF. |

| National Runaway Safeline

The FYSB at ACF operates the National Runaway Safeline, which supports youth who have run away. |

|

| United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH)

USICH was created in 1987 via McKinney-Vento to coordinate the federal government’s response to homelessness across 19 federal agencies. |

In March 2025, President Trump issued an executive order (EO) to eliminate the USICH. This action raises concerns about the future coordination of federal efforts to address homelessness. |

Research

The federal government plays a critical role in collecting and disseminating data on children and youth experiencing homelessness. It also supports research that focuses on identifying best practices to improve academic and other short- and long-term outcomes for this group of students.

Table 3: Federal Support for Research on Students Experiencing Homelessness

Historical Federal Role |

Changes Under Trump Administration |

|---|---|

| NCHE Research

NCHE provides research on educating homeless children and youth. |

There have been no changes to NCHE as of June 18, 2025; however, it is unlikely that NCHE will continue to conduct research if EHCY is eliminated. |

| National Center for Education Statistics (NCES)

The NCES at the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES) funds |

In February 2025, the Trump administration canceled $900 million in contracts at IES. In March 2025, nearly all the staff at NCES were fired. These cuts threaten the ability of IES and NCES to provide necessary data reporting and research. |

| U.S. Department of Education’s ED Data Express

The ED Data Express dashboard compiles and releases state-level data on student homelessness annually, including data on funding levels, student participation, and student performance data. |

In March 2025, President Trump issued an EO to close the U.S. Department of Education. Following the EO, the Department cut nearly 2,000 jobs. In May 2025, a federal judge ordered the Department to reinstate these employees, though whether that happens remains to be seen. If not reversed, this substantial downsizing is likely to impact the Department’s ability to collect, analyze, and share data on students experiencing homelessness. |

| ACF Data Collection and Reporting

ACF collects data, provides regular updates to Congress, and conducts research on child welfare-related issues. |

Downsizing at HHS and ACF will likely impact the Department’s ability to collect, analyze, and share data on homeless and other vulnerable populations of students. |

Monitoring and Oversight

The federal government has established the rights that homeless students are entitled to and plays a critical role in protecting those rights and ensuring states and districts uphold them.

Table 4: Federal Monitoring and Oversight of the Rights of Students Experiencing Homelessness

Historical Federal Role |

Changes Under Trump Administration |

|---|---|

| Homeless Students’ Rights

McKinney-Vento details the specific rights students experiencing homelessness have, including the right to remain in their school of origin and the right to immediate enrollment, free transportation, and access to programming such as preschool, special education services, and nutrition services. McKinney-Vento also gives parents, guardians, and unaccompanied youths the right to dispute eligibility, school selection, or enrollment decisions. |

As of June 18, 2025, the U.S. Department of Education has been silent on whether it intends to pursue changes to ESEA. However, if EHCY is eliminated (via its consolidation into a block grant), there will no longer be monitoring of the rights and services the program currently provides. |

| McKinney-Vento Data Reporting Requirements

McKinney-Vento requires states and LEAs to collect and report data on homeless children and youth, data on the services provided to those students, and outcome data (including chronic absenteeism, graduation rates, and math, English language arts, and science achievement). This data is reported to the U.S. Department of Education; the Department makes data publicly available. |

If EHCY is eliminated, it is unlikely that the federal government will continue to require states to collect and report data on students experiencing homelessness, leading to the loss of critical data. |

Additional Federal Actions Affecting Students Experiencing Homelessness

Some policy and legal actions taken by the Trump administration do not alter existing federal responsibilities to support students experiencing homelessness; rather, they introduce additional potential challenges for these students. For example:

- Immigration enforcement targeting unaccompanied minors: Many immigrants — sometimes unaccompanied minors — arrive in the U.S. without stable housing. Under the Trump administration, immigration enforcement efforts targeting unaccompanied minors have intensified, potentially impacting those who may also be experiencing homelessness. To facilitate immigration enforcement, the Trump administration has allowed for data-sharing between the Office of Refugee Resettlement and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a major shift that puts sensitive information about unaccompanied minors and their sponsors at risk of being used for deportation purposes. In March 2025, the administration nearly terminated legal representation for unaccompanied minors, leaving thousands of children at risk of navigating complex immigration proceedings alone, though the courts have since temporarily restored funding for these services. In the last several months, federal agents, primarily from Homeland Security Investigations, have conducted or attempted to conduct unannounced “wellness checks” at schools, homes, and migrant shelters — heightening fear among unaccompanied minors and those with unstable housing, and contributing to increased school absenteeism.

- Cuts to programs for vulnerable populations: The U.S. Department of Agriculture is planning to cut funding that helps schools purchase food from local farmers, which will disrupt school food services and lower the quality of meals provided to students. These changes will disproportionately affect students who rely on school meals, including homeless youth who are automatically eligible for free and reduced-price meals through direct certification. Interruptions in food service and declines in meal quality are likely to further exacerbate food insecurity among these already vulnerable children. Other proposed federal budget cuts threaten to reduce or eliminate funding for critical programs that support vulnerable populations, including the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and Medicaid. These cuts would likely have a significant negative impact on youth experiencing homelessness, as these programs provide essential support for housing stability, nutrition, and health care. The administration’s budget also proposes deep reductions to affordable and supportive housing programs, which, if enacted, could result in the loss of housing for hundreds of thousands of low-income households and increased barriers to accessing assistance.

- Terminating diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts: The Trump administration’s broader policy agenda includes halting funding for DEI initiatives across federal agencies, as outlined in recent EOs. These measures have been described as a significant setback for marginalized groups, including Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ youth, who are disproportionately represented among homeless young people and face unique challenges in accessing safe and supportive environments. The removal of DEI-related funding and programs may make it more difficult for homeless and at-risk youth to find supportive resources and safe educational settings, potentially exacerbating their marginalization and increasing their vulnerability to homelessness and related harms.

Actions State Leaders Can Take to Support Homeless Students Through Federal Disruption

The changing federal role in the education of pre-K through Grade 12 students experiencing homelessness presents opportunities for state leaders to clarify, improve, or modify their own policies to support this student population. State leaders, including those in governors’ offices, SEAs and boards, and legislatures, should do the following:

1. Engage in the federal policy conversation and share local impact.

State leaders can play a critical role in shaping national policy. State education officials, legislators, and governors’ offices should maintain regular communication with their U.S. senators and representatives to ensure they understand the real-world impact of federal decisions on students experiencing homelessness. Sharing data, stories, and concrete examples from schools and communities can illuminate how federal program changes — such as the consolidation or elimination of targeted funding — would affect students on the ground. This engagement can contribute to a more accurate federal understanding of homelessness and help guard against unintended consequences of policy shifts.

2. Codify protections for homeless students in state law.

States must strengthen and clarify the rights and protections for students experiencing homelessness by embedding them in state statutes and regulations, ensuring consistent and comprehensive support regardless of changes at the federal level. McKinney-Vento establishes a federal baseline of protections. However, the U.S. Department of Education’s FY26 budget consolidates McKinney-Vento’s EHCY program and 17 other federal grant programs into a single block grant, effectively eliminating the program and erasing federal protections for homeless students, including immediate enrollment, school stability, transportation, and access to all educational programs. States must ensure that the full range of McKinney-Vento protections are explicitly codified in state law.

Once states have codified this baseline of protections, states should consider expanding upon them to address local gaps and challenges. In particular, matters concerning the rights of minors, as well as health care, housing, employment, education, and child welfare, fall under the jurisdiction of state legislatures.

3. Establish or increase state-level funding for students experiencing homelessness.

While several analyses suggest that current McKinney-Vento funding levels are inadequate, it is the primary — and often only — source of funds that schools and districts have to provide services for students experiencing homelessness. Only a handful of states have dedicated funding to support young people experiencing homelessness beyond federal funds. And while all LEAs are required to adhere to federal requirements for serving homeless students, only about 20% of LEAs receive McKinney-Vento subgrants to support that work. The remaining districts must fund liaisons and address student needs out of their own operating budgets.

The reality of federal funding inadequacy, coupled with a U.S. Department of Education budget proposal that eliminates EHCY entirely, makes it more important than ever for states to provide funding to LEAs to support students experiencing homelessness. States could provide funding through a variety of mechanisms, including developing a student funding formula that includes weights for students experiencing homelessness, providing annual funding for transportation or other services, or offering grants to support coordination across districts and communities. Importantly, any state funding for homeless students must be flexible — local district and school leaders must be able to use those funds in ways that meet the unique needs of the individual students they serve.

4. Maintain and publicly report data on student homelessness.

As the federal role in education for students experiencing homelessness evolves, states have an opportunity to strengthen their own data systems. While McKinney-Vento requires SEAs to collect, maintain, and publicly report data on students experiencing homelessness, the nuances of data collection and public dissemination beyond federal requirements are left to states. For example, some states go beyond federal minimums by collecting additional data points, such as how LEAs are using funds dedicated to students experiencing homelessness to better inform state and local policy and practice, but not all do.

States must take the lead in collecting data on homeless students and how they are served, including how districts are using Title I set-asides, and in making that data transparent to the public. Including data on homeless students directly in state report card websites, for example, can help states hold themselves accountable for serving homeless students — and ensure state leaders have the data they need to allocate resources more effectively.

5. Create mechanisms to facilitate or enhance cross-agency collaboration and coordination.

Historically, federal policy has emphasized the necessity of cross-agency collaboration to address the complex needs of students experiencing homelessness. In alignment with this, states should formalize cross-agency partnerships through interagency working groups, memoranda of understanding, and joint initiatives, ensuring that collaboration is not left to chance but embedded in policy and practice. Strong collaboration should involve data-sharing agreements that protect student privacy while helping agencies better support homeless students, as well as state grants or incentives for joint efforts that address barriers to attendance, stability, and academic success.

6. Invest in professional development around best practices for serving students experiencing homelessness.

Professional development is critical to building awareness and capacity among school personnel to identify and support students experiencing homelessness. While McKinney-Vento requires that all schools provide training on the requirements and ways to support students experiencing homelessness effectively, the nuances of this training and its implementation are locally controlled. In the context of evolving federal policy and role, states should ensure that training is ongoing and includes updates on policy changes and best practices for supporting students experiencing homelessness.

State leaders would also benefit from training on best practices and allowable uses of funding for homeless students. State finance officers who review district budgets, for example, may not understand why a district is spending money on diapers, even as the local liaison knows that those diapers are what allows a young mother to send her child to day care so she can attend school. Training for state leaders can help bridge these gaps and ensure widespread understanding of best practices to support homeless students.

7. Strengthen the capacity of state homeless coordinators and local liaisons.

State homeless coordinators and local liaisons play an essential role in identifying students experiencing homelessness, ensuring they are enrolled in school and can attend, navigating often-complex webs of social services to access services, coordinating with other state and local agencies, and training school and district staff members to support these students. All of these activities are required by federal law. However, district liaisons are often stretched thin: One survey found that more than 90% of liaisons work in another official capacity in the district; 89% say they spend less than half of their time on liaison-related duties.

This limited capacity can significantly undermine efforts to identify homeless students early, ensure consistent school attendance, and connect families with vital services. As federal uncertainty grows, it is essential that states step in to dedicate funding, staffing, and training resources to these roles. States might consider funding full-time liaison positions, setting minimum time allocation requirements, or providing supplemental grants to high-need districts. Investing in these positions both supports academic continuity for young people and strengthens the broader safety net for some of the most vulnerable students in the education system.

Considerations for State Policymakers and Advocates

Federal programmatic and funding uncertainty places even more responsibility on state policymakers to develop and implement effective policies that support and serve students experiencing homelessness. To anticipate and embrace this responsibility, state policymakers should consider the following set of strategic questions.

Stakeholder Engagement:

- Do you regularly engage with key stakeholders, including students experiencing homelessness, their families, district leaders and educators who work with homeless populations, shelters, and community-based and advocacy organizations that work on behalf of homeless youth?

- If not, how could those relationships be strengthened? Are there additional partnerships that need to be formed?

- If so, are you discussing the impact of federal policy changes and addressing stakeholder questions and concerns?

- How are policymakers informing stakeholders about changes in federal policy and their implications for state and local services?

- What mechanisms or channels exist for students experiencing homelessness, their families, shelters, and community advocates to provide input on new policies or services that affect them?

- How are cross-sector leaders — including those in early childhood, education, health and human services, housing, juvenile justice, the attorney general, and immigration — collaborating and jointly problem-solving around state responses?

Policy and Budget:

- Are existing state laws aligned with or exceeding McKinney-Vento protections? Are there gaps that need to be addressed as federal oversight recedes?

- How will the state ensure the rights and protections of homeless students remain robust if federal enforcement wanes?

- How is the state addressing and protecting the needs of young people disproportionately experiencing homelessness, including those who face unique risks such as unaccompanied minors and LGBTQ+ youth, given the current federal environment?

- How engaged are state leaders in addressing threats to homeless students?

- What might it take to secure sufficient political support to advance state action to strengthen support for homeless students?

- Which groups or individuals are most outspoken or influential on issues related to homelessness education? What are they advocating for (or against)?

- Does the state provide dedicated funding to supplement or replace federal dollars?

Implementation and Assistance:

- How is the state monitoring compliance with McKinney-Vento requirements given reduced federal oversight?

- Are districts receiving timely training, resources, and support?

- What systems are in place to maintain data collection and reporting in the event of disruptions to federal data-sharing infrastructure?

- How are agencies sharing data and coordinating service delivery to reduce duplication and address gaps?

- What state-level innovations or best practices could be scaled to fill gaps left by reduced federal involvement?

OTHER RESOURCES

- Continuity Counts, Bellwether

- National Center for Homeless Education, Department of Education

- Federal and State Resources for Students Experiencing Homelessness, Learning Policy Institute

- History of McKinney-Vento Act’s Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program, SchoolHouse Connection

Sources

Summary:

Data for McKinney-Vento Act, school year 2022–2023, ED Data Express, https://eddataexpress.ed.gov/download/data-builder/data-download-tool?f[0]=program:McKinney-Vento%20Act&f[1]=school_year:2022-2023.

Child and Youth Homelessness in the United States: Data Profiles, Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan and SchoolHouse Connection, https://poverty.umich.edu/research-funding-opportunities/data-tools/child-and-youth-homelessness-in-the-united-states-data-profiles/.

“Part III: Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Equity: Disproportionality and Action Steps for Schools,” in Student Homelessness: Lessons from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (School House Connection, n.d.), https://schoolhouseconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/imported-files/YRBS-Part-III-Sexual-Orientation-and-Gender-Identity-Equity.pdf.

Daniel Espinoza et al., “Federal and State Resources for Students Experiencing Homelessness,” Learning Policy Institute, updated May 12, 2023, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/federal-state-resources-students-experiencing-homelessness-brief.

“Chronic Absence & Homelessness,” SchoolHouse Connection, https://schoolhouseconnection.org/article/chronic-absence.

Espinoza et al., “Federal and State Resources.”

Izraelle I. McKinnon et al., “Experiences of Unstable Housing Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2021,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72, no. S1 (2023): S29–S36, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/su/su7201a4.htm.

“Part X: Pregnancy Rates of High School Students Experiencing Homelessness,” in Student Homelessness:

Lessons from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (School House Connection, n.d.), https://schoolhouseconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/imported-files/YRBS-Part-X-Pregnancy.pdf.

See, for example, Daniel Espinoza et al., Federal and State Resources for Students Experiencing Homelessness (Learning Policy Institute, 2023), https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/federal-state-resources-students-experiencing-homelessness-report; Chronic Absenteeism Among Students Experiencing Homelessness in America: School Years 2016-17 to 2020-21 (National Center for Homeless Education, 2022), https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Homeless-Student-Absenteeism-in-America-2022.pdf.

The Public Health and Welfare Act, 42 U.S.C. § 11434a(2)(A) and (B), https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title42/chapter119/subchapter6/partB&edition=prelim.

The Public Health and Welfare Act, 42 U.S.C. § 11434a(6), https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title42/chapter119/subchapter6/partB&edition=prelim.

Definitions of Homelessness for Federal Program Serving Children, Youth, and Families (Administration for Children and Families, 2011), https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ecd/homelessness_definition_0.pdf.

“Four Categories of the Homeless Definition,” HUD Exchange, https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/coc-esg-virtual-binders/coc-esg-homeless-eligibility/four-categories/.

“Category 1: Literally Homeless,” HUD Exchange, https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/coc-esg-virtual-binders/coc-esg-homeless-eligibility/four-categories/category-1/.

“Category 3: Homeless under Other Federal Statutes,” HUD Exchange, https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/coc-esg-virtual-binders/coc-esg-homeless-eligibility/four-categories/category-3/.

Federal Role in Homeless Students’ Education and Changes Under the Trump Administration:

McKinney-Vento Act: Quick Reference (SchoolHouse Connection, 2024), https://schoolhouseconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/McKinney-Vento-Act-Quick-Reference-August-2024.pdf.

The Public Health and Welfare Act, 42 U.S.C. § 11431(2), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2010-title42/html/USCODE-2010-title42-chap119-subchapVI-partB.htm.

Education for Homeless Children and Youths (EHCY) Program Profile (U.S. Department of Education, 2023), https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/ehcy_profile.pdf.

2025 Fact Sheet: Educating Children and Youth Experiencing Homelessness (SchoolHouse Connection, 2025), https://schoolhouseconnection.org/article/2025-fact-sheet-educating-children-and-youth-experiencing-homelessness.

“Education for Homeless Children and Youths,” Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, U.S. Department of Education, updated March 7, 2025, https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/formula-grants/formula-grants-special-populations/education-for-homeless-children-and-youths.

The Public Health and Welfare Act, 42 U.S.C. § 11432(f).

The Public Health and Welfare Act, 42 U.S.C. § 11432(g)(6)(A).

Espinoza et al., Federal and State Resources.

“ESG: Emergency Solutions Grants Program,” HUD Exchange, https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/esg/.

Fact Sheet: Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025 (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2025), https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Fact-Sheet-Full-Year-Continuing-Appropriations-and-Extensions-Act.pdf.

Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request (Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, 2025), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Fiscal-Year-2026-Discretionary-Budget-Request.pdf.

“Trump Administration’s “Skinny” Budget Request Foreshadows Massive Cuts, Changes to HUD Programs – Take Action!” National Low Income Housing Coalition, May 5, 2025, https://nlihc.org/resource/trump-administrations-skinny-budget-request-foreshadows-massive-cuts-changes-hud-programs.

Mindy Mitchell, Homeless Assistance: McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Programs (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2019), https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/AG-2019/04-15_Homeless-Assistance-McKinney-Vento.pdf.

Fact Sheet: Full-Year Continuing Appropriations.

Libby Miller, “National Alliance to End Homelessness Statement on President Trump’s FY2026 Federal Budget Proposal,” National Alliance to End Homelessness, May 5, 2025, https://endhomelessness.org/media/news-releases/national-alliance-to-end-homelessness-statement-on-president-trumps-fy2026-federal-budget-proposal/.

“YHDP: Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program,” HUD Exchange, https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/yhdp/.

Fact Sheet: Full-Year Continuing Appropriations.

“Education for Homeless Children and Youths.”

U.S. Department of Education Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Summary (U.S. Department of Education, 2025), https://www.ed.gov/media/document/fiscal-year-2026-budget-summary-110043.pdf.

Serving Students Experiencing Homelessness under Title I, Part A (National Center for Homeless Education, 2017), https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/titlei.pdf.

Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request.

U.S. Department of Education Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Summary.

“American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief – Homeless Children and Youth (ARP-HCY): Home,” Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, U.S. Department of Education, updated April 10, 2025, https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/formula-grants/response-formula-grants/covid-19-emergency-relief-grants/american-rescue-plan-elementary-and-secondary-school-emergency-relief-mdash-homeless-children-and-youth-arp-hcy.

M. Malone et al., State and Local Implementation Studies of the American Rescue Plan – Homeless Children and Youth (ARP-HCY): National Outcomes Summary (Office of School Support and Accountability, U.S. Department of Education, 2025), https://www.ed.gov/media/document/arp-hcy-national-outcomes-summary-109427.pdf.

“American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief – Homeless Children and Youth (ARP-HCY): Frequently Asked ARP-HCY Questions and Answers,” Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, U.S. Department of Education, updated April 10, 2025, https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/formula-grants/response-formula-grants/covid-19-emergency-relief-grants/american-rescue-plan-elementary-and-secondary-school-emergency-relief-mdash-homeless-children-and-youth-arp-hcy#frequently-asked-arp-hcy-questions-and-answers.

Linda McMahon to State Chiefs of Education, Washington, D.C., March 28, 2025, https://www.ed.gov/media/document/letter-state-chiefs-esf-funding-march-28-2025-109778.pdf.

“Runaway and Homeless Youth,” Family and Youth Services Bureau, updated February 18, 2025, https://acf.gov/fysb/programs/runaway-homeless-youth.

Nathaniel Weixel, “Trump Dismantles, Cuts and Shakes Up World of Health in First 100 Days,” The Hill, April 29, 2025, https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/5271799-trump-health-policy-changes/.

Ron Wyden and Bernard Sanders to Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Washington, D.C., April 15, 2025, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/acf_reduction_in_force_letter.pdf.

“Head Start Services,” Administration for Children and Families, https://acf.gov/ohs/about/head-start.

“Children and Families Experiencing Homelessness,” Head Start, updated May 30, 2025, https://headstart.gov/family-support-well-being/article/children-families-experiencing-homelessness.

Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request.

“The National Center for Homeless Education,” National Center for Homeless Education, https://nche.ed.gov/.

“Focus Areas,” Administration for Children and Families, updated November 22, 2024, https://acf.gov/cb/focus-areas.

“Children’s Bureau (CB),” Administration for Children and Families, https://acf.gov/cb.

Weixel, “Trump Dismantles, Cuts and Shakes Up.”

Wyden and Sanders to Kennedy, April 15, 2025.

Eli Hager, “The Trump Administration’s War on Children,” ProPublica, April 23, 2025, https://www.propublica.org/article/how-trump-budget-cuts-harm-kids-child-care-education-abuse.

“1800Runaway.org,” National Runaway Safeline, https://www.1800runaway.org/.

“USICH,” United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, https://www.usich.gov/about/usich.

“Continuing the Reduction of the Federal Bureaucracy,” The White House, updated March 14, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/continuing-the-reduction-of-the-federal-bureaucracy/.

“Homeless Education Research,” National Center for Homeless Education, https://nche.ed.gov/research/.

“The National Center for Homeless Education.”

See, for example, Haigen Huang, “Risk and Resilience in Children Experiencing Homelessness,” Institute of Education Sciences Blog, November 16, 2023,

https://ies.ed.gov/learn/blog/risk-and-resilience-children-experiencing-homelessness; “Developing a Coordinated System to Identify and Support Students Experiencing Homelessness,” Institute of Education Sciences, https://ies.ed.gov/use-work/awards/developing-coordinated-system-identify-and-support-students-experiencing-homelessness.

Kalyn Belsha, “Crucial Research Halted as DOGE Abruptly Terminates Education Department Contracts,” Chalkbeat, February 11, 2025, https://www.chalkbeat.org/2025/02/11/elon-musk-and-doge-cancel-education-department-research-contracts/.

Benjamin Siegel, “Education Department Cuts Agency That Compiles ‘Nation’s Report Card’ and Measures Student Performance,” ABC News, March 12, 2025, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/education-department-cuts-agency-compiles-nations-report-card/story?id=119735831.

“Homeless Enrolled Students by State,” ED Data Express, https://eddataexpress.ed.gov/dashboard/homeless/2022-2023?sy=2955&s=1035.

“Improving Education Outcomes by Empowering Parents, States, and Communities,” The White House, updated March 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/improving-education-outcomes-by-empowering-parents-states-and-communities/.

Laura Mannweiler, “Education Department Fires over 1,300 Workers, Gutting Its Staff,” U.S. News & World Report, March 12, 2025, https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2025-03-12/the-education-department-cuts-nearly-2-000-employees-what-to-know#google_vignette.

Danielle Douglas-Gabriel and Laura Meckler, “Education Department Must Reinstate Nearly 1,400 Fired Workers,” Washington Post, May 22, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2025/05/22/education-department-fired-federal-workers-reinstated/.

“Resource Library: Congressional Reports,” Administration for Children and Families, https://acf.gov/cb/resource-library?f%5B0%5D=report_type%3A613.

“Resource Library: Research,” Administration for Children and Families, https://acf.gov/cb/resource-library?f%5B0%5D=report_type%3A614.

Education for Homeless Children and Youths Program Non-Regulatory Guidance (U.S. Department of Education, 2016), https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/policy/elsec/leg/essa/160240ehcyguidance072716.pdf; Supporting the Success of Homeless Children and Youths (U.S. Department of Education, 2016), https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/policy/elsec/leg/essa/160315ehcyfactsheet072716.pdf.

The Public Health and Welfare Act, 42 U.S.C. Chapter 119, Subchapter VI, Part B: Education for Homeless Children and Youths, https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title42/chapter119/subchapter6/partB&edition=prelim.

The Data Collection Process and Students Experiencing Homelessness (National Center for Homeless Education, 2022), https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2022-The-Data-Collection-Process-and-Students-Experiencing-Homelessness.pdf.

Additional Federal Actions Affecting Students Experiencing Homelessness:

“Resources to Support Immigrant and Migrant Students Experiencing Homelessness,” SchoolHouse Connection, https://schoolhouseconnection.org/article/resources-to-support-immigrant-and-migrant-students-experiencing-homelessness.

See, for example, José Olivares, “Ice Seeking Out Unaccompanied Immigrant Children to Deport or Prosecute,” Guardian, April 28, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/apr/28/ice-unaccompanied-immigrant-children; Marisa Taylor et al., “Trump Officials Launch ICE Effort to Deport Unaccompanied Migrant Children,” Reuters, February 23, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-administration-directs-ice-agents-find-deport-unaccompanied-migrant-2025-02-23/.

Mark Rattner, “Senator Wyden Demands Halt to Info Sharing That Risks Child Safety,” NBC News, April 3, 2025, https://www.nbcrightnow.com/news/senator-wyden-demands-halt-to-info-sharing-that-risks-child-safety/article_03024a8c-f3c6-11ef-8c0c-9b87b4413623.html.

“Unaccompanied Alien Children – 2025 Update,” National Immigration Forum, updated April 2, 2025, https://immigrationforum.org/article/unaccompanied-alien-children-ucs-or-uacs-2025-update/.

Michael D. Shear and Zolan Kanno-Youngs, “Checks on Migrant Children by Homeland Security Agents Stir Fear,” The New York Times, May 28, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/28/us/trump-ice-migrant-children-welfare-checks.html; David Montgomery, “Immigration Raids Add to Absence Crisis for Schools,” The New York Times, June 16, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/16/us/immigration-raids-school-absences-deportation-fears.html

Brooke Schultz, “Trump Admin. Cuts Program That Brought Local Food to School Cafeterias,” EducationWeek, March 11, 2025, https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/trump-admin-cuts-program-that-brought-local-food-to-school-cafeterias/2025/03.

“Identifying and Supporting Students Experiencing Homelessness from Pre-School to Post-Secondary Ages,” Office of Communications and Outreach, U.S. Department of Education, March 19, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/teaching-and-administration/supporting-students/identifying-and-supporting-students-experiencing-homelessness-from-pre-school-to-post-secondary-ages-us-department-of-education.

Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request.

Katie Bergh, “Millions of Low-Income Households Would Lose Food Aid Under Proposed House Republican SNAP Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 24, 2025, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/millions-of-low-income-households-would-lose-food-aid-under-proposed-house; House Committee on Agriculture, 119th Cong., Document Providing Reconciliation Pursuant to H. Con. Res. 14 (Comm. Print 2025), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AG/AG00/20250513/118259/BILLS-119pih-CommitteePrint-U1.pdf.

Nathaniel Weixel, “GOP Medicaid Debate Intensifies as Republicans Search for Cuts,” The Hill, April 27, 2025, https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/5268561-house-republicans-medicaid-cuts/; Lisa Mascaro, “House Republicans Have Unveiled Proposed Medicaid Cuts. Democrats Say Millions Will Lose Coverage,” PBS News, May 12, 2025, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/house-republicans-have-unveiled-proposed-medicaid-cuts-democrats-say-millions-will-lose-coverage.

Jason DeParle, “Trump Seeks to End Permanent Supportive Housing for the Chronically Homeless,” New York Times, May 2, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/02/us/politics/trump-homelessness-programs-housing-cuts.html; “Trump Administration’s “Skinny” Budget Request.”

“Trump’s Executive Orders on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Explained,” Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, updated February 12, 2025, https://civilrights.org/resource/anti-deia-eos/.

Mel Wilson, “Trump’s DEI Executive Order: Only the Beginning of Attacks on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” National Association of Social Workers, https://www.socialworkers.org/Advocacy/Social-Justice/Social-Justice-Briefs/Trumps-DEI-Executive-Order-Only-the-Beginning-of-Attacks-on-Diversity-Equity-and-Inclusion; “Homelessness and Housing Instability among LGBTQ Youth,” Trevor Project, updated February 3, 2022, https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/homelessness-and-housing-instability-among-lgbtq-youth-feb-2022/; “Centering Youth of Color & LGBTQ Young People in Efforts to End Homelessness,” United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, updated February 12, 2018, https://www.usich.gov/news-events/news/centering-youth-color-lgbtq-young-people-efforts-end-homelessness#.

“Homelessness and Housing Instability among LGBTQ Youth.”

Actions State Leaders Can Take to Support Homeless Students Through Federal Disruption

U.S. Department of Education Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Summary.

“State Laws to Support Youth Experiencing Homelessness,” SchoolHouse Connection, https://schoolhouseconnection.org/article/state-laws-to-support-youth-experiencing-homelessness.

See Seen and Served: How Dedicated Federal Funding Supports the Identification of Students Experiencing Homelessness (SchoolHouse Connection, n.d.), https://schoolhouseconnection.org/article/seen-and-served-how-dedicated-federal-funding-supports-the-identification-of-students-experiencing-homelessness; Espinoza et al., Federal and State Resources.

“White House Issues Executive Order to Dismantle ED: Federal Protections for Homeless Students Still in Place – But the Risks Are Real,” SchoolHouse Connection, https://schoolhouseconnection.org/article/white-house-issues-executive-order-to-dismantle-ed; Espinoza et al., Federal and State Resources.

Seen and Served.

U.S. Department of Education Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Summary.

Espinoza et al., Federal and State Resources.

Guide to Collecting & Reporting Federal Data: Education for Homeless Children & Youth Program (National Center for Homeless Education, 2019), https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Data-Collection-Guide-SY-18.19.pdf.

Espinoza et al., Federal and State Resources.

When Working Together Works: Interagency Collaboration between McKinney-Vento Programs and Homeless Service Providers (National Center for Homeless Education, 2019), https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Working-Together.pdf.

See, for example, Espinoza et al., Federal and State Resources.

“Navigating McKinney Vento Training for School Staff,” Public School Works, https://corp.publicschoolworks.com/resource/navigating-mckinney-vento-training-for-school-staff/#:~:text=McKinney%2DVento%20Training%20Requirements,Tutoring%20and%20other%20academic%20supports.

See, for example, Erica Meaker to District Superintendents, Superintendents of LEAs, Charter School Principals, Title I Coordinators, McKinney-Vento Liaisons, and Committee on Special Education (CSE) Chairs, Albany, August 23, 2024, https://www.nysed.gov/memo/essa/mandatory-mckinney-vento-homeless-assistance-act-training-2024-25-school-year.

Homeless Students Count: How States and School Districts Can Comply with the New Mckinney-Vento Education Law Post-Essa (National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, 2018), https://homelesslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Homeless-Students-Count.pdf.

Acknowledgments, About the Authors, About Bellwether

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our Bellwether colleague Hailly T.N. Korman for her input and Barbara Duffield and Erin Patterson for reviewing and providing feedback on an early draft. Thank you to Amy Ribock, Kate Stein, Andy Jacob, McKenzie Maxson, Zoe Cuddy, Julie Nguyen, Mandy Berman, and Amber Walker for shepherding and disseminating this work, and to Super Copy Editors.

The contributions of these individuals and entities significantly enhanced our work; however, any errors in fact or analysis remain the responsibility of the authors.

About the Authors

Kelly Robson Foster

Teresa Mooney

Bellwether is a national nonprofit that exists to transform education to ensure systemically marginalized young people achieve outcomes that lead to fulfilling lives and flourishing communities. Founded in 2010, we work hand in hand with education leaders and organizations to accelerate their impact, inform and influence policy and program design, and share what we learn along the way. For more, visit bellwether.org.