Education is a complicated and costly endeavor, and nuance is usually a good thing in school funding formulas. But, in seeking to account for variations in context, some states risk overcomplicating, or even undermining, the goals of their funding formulas.

The base amount in a K-12 student-based state school funding formula is intended to represent the cost of educating a student with no special needs (e.g., special education needs) or disadvantages (e.g., economic disadvantage). Every enrolled student generates at least the base amount for their school district. The base provides a clear, shared starting place for school funding expectations.

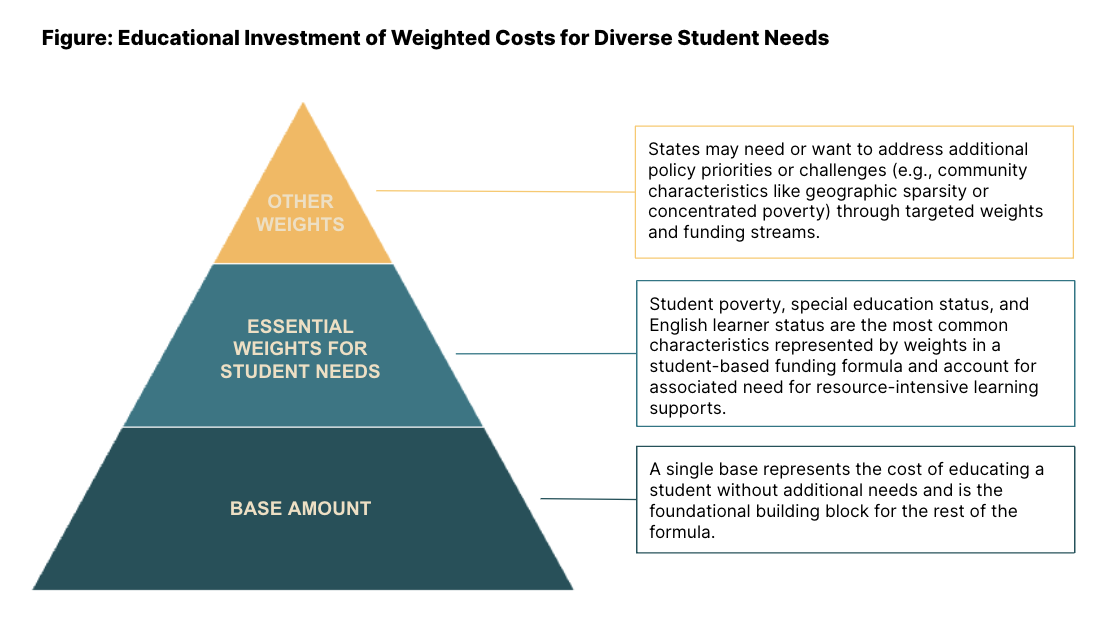

In most weighted, student-based funding formulas, states use a base cost and build upon it with a variety of student- or community-based weights for characteristics such as student poverty or English learner status (Figure). Student- and community-based amounts are added together to arrive at a total formula funding amount for each district, which determines the allocation of state and local funds.

Figure: Educational Investment of Weighted Costs for Diverse Student Needs

The base cost is the building block of every funding allocation decision that comes after it. There are different ways to create a base cost, with different implications for the impact and equity of the funding formula.

The simplest, and by far the most popular option, is to have one consistent base cost for every student. The key benefits of this model are simplicity, transparency, and predictability, from which different weights and other funding allocation decisions build.

But a simple base may omit important nuances in the cost of educating a student. To answer this issue, some states use a variable base to account for complexity that isn’t represented in the weights. This usually comes from a desire to account for cost differences among districts, based on factors such as district size, regional economic differences, or grade-level configurations.

However, the nuances added in a variable base may not always be a win for the formula as a whole, as examples from Colorado and Nevada illustrate.

A CLOSER LOOK:

Splitting the Bill: How Does the Base Amount Work in Student-Based Funding Formulas? explains policy options, pros, and cons for different methods to calculate base amounts. Several states with variable, complex base costs illustrate risks that policymakers should consider.

Colorado: Cost of Living Magnifies Inequities

Take Colorado, for instance. Its state funding formula assigns a Cost of Living (COL) factor that modifies the base cost for each district, ranging from approximately 1% to 65%, based on the district’s cost of living compared to other communities in the state. But the current structure of the variable base significantly amplifies inequities because it heavily favors areas that tend to be wealthier, with lower levels of student need. Then, when weights are added on that variable base, high cost of living areas with lower student need get even more state funding per pupil. At present, COL adjustments drive an outsized 15% of total Colorado education funding and widen existing disparities.

Colorado is currently reexamining its variable base and COL factor as part of a legislatively mandated public school finance task force, with potential changes expected to be brought to the legislature in early 2025.

Nebraska: Complex Individual Base Costs Decrease Transparency

Nebraska has one of the most complex base cost formulas in the country. To calculate a custom base for each district, the state first identifies a comparison group of 20 similar-sized districts based on student enrollment, then removes outliers and does an additional calculation for small districts — all to arrive at a bespoke base for every district.

Not only is this formula complex, but it’s also circuitous: Expenditures drive the base cost which drives expenditures.

Reforming the state’s base calculation is not at the top of the agenda for Nebraska policymakers and advocates, who have been busy with a recent package of education finance bills aimed at increasing the state’s investment in education. That said, current momentum may continue in the 2024 and beyond to open the door to more structural reforms to Nebraska’s system.

Colorado and Nebraska, along with other states across the country, are running up against the hidden challenges of a variable base in education funding formulas. While the intention may be to increase nuance and fairness for districts, the benefits of a complex variable base may not be worth the increased complexity, reduced transparency, and unintended equity implications. In most cases, a state’s education funding equity and efficiency goals are better served through a simple, transparent base, with nuance provided by well-designed and equitable weights, along with fair local share policies.

For more from Bellwether on state education finance, click here.