Charter School Board Playbook

By Carrie C. Irvin and Caitlin Piccirillo-Stosser

Boards Matter for Students

Most students don’t know who is on the board of their school. Board members don’t teach classes, coach sports teams, or serve lunch. Many parents who send their children to public charter schools don’t realize that the school has its own board. Even many charter school teachers don’t quite realize the role of the board.

However, board members make an enormous difference in how every parent, teacher, and most importantly student experiences the school. What happens in the board room directly impacts what happens in the classroom. In fact, what happens in the board room makes what happens in the classroom possible.

Serving on the board of a public charter school is a unique and special opportunity to make a meaningful difference in a community. It’s also a huge responsibility. Students depend on board members to make sure their school is high quality. And collectively, the success of public charter schools depends on every single school having a great board.

To be a great board member requires diligence, consistency, decisiveness in the face of complexity — and a lot of time, which is sometimes the hardest part for busy volunteers. The best board members we know bring sound judgment, sensitivity, and courage in service of the students they serve.

But no one instinctively knows how to be a great board member. No one majored in charter school governance, it’s no one’s hobby, and frankly, there are no perfect boards to just copy. This kind of governance in public education hasn’t been around that long. There’s barely any research about it. And it’s hard. In our experience, all board members need (and most want) relevant training, useful and straightforward resources, and real-time support to help them figure out what to do.

This playbook is designed to get that information to charter school board members and school leaders.

Accountability is the board’s main job.

Most public school districts have elected boards that govern a school system with many layers, levels, and structures. Charter schools, however, are public schools that operate outside most structures of traditional districts. While they are publicly funded, charter schools are governed by nonelected school-level (or school network-level) boards. This difference in governance is perhaps the most important difference between charter schools and district schools.

Charter schools have more autonomy than district schools to understand what catalyzes and advances student learning, make decisions about how to educate their students, and quickly move on from strategies that do not improve student learning.

This autonomy can power student success. And it comes with conditions. Charter schools, in theory, are more accountable than district schools: If a school does not fulfill the promises in its charter, does not meet authorizer requirements, and does not provide a high-quality education, the authorizer of that school can close it.

But here’s the rest of the accountability deal: Accountability rests first and foremost with the board of each school. Regardless of the actions or decisions of authorizers, funders, or other stakeholders, it’s up to the board of every charter school and network to hold the school accountable for educating its students. Every charter school authorizer — the legal entity that can approve (and revoke) charters — creates a binding agreement between itself and the board of the school. That agreement, the charter, is granted to the board of that school — not parents, not the school leader, and not the authorizer itself. Thus, every board is responsible for knowing whether the school is fulfilling the promises outlined in its charter, and taking action if it’s not.

The board of every school must keep the promises in the charter central, measure school progress toward those promises, and refuse to lower expectations when the going gets tough. That’s the board’s main job — keep the bar high, and don’t lower expectations. Ever.

Great boards know what they’re supposed to do, and they do it.

Effective boards consistently and courageously monitor key metrics of school success.

DO:

- Ask well-informed questions to fully understand what the data shows.

- Regularly and openly discuss with school leadership what needs to happen to get back on track.

- Celebrate when key metrics are on track, and learn from wins.

DON’T:

- Hesitate to engage in the core work of the board: oversight of academic outcomes and school quality.

- Get distracted, waste time, or ignore the important in favor or what feels urgent.

- Buy into the incorrect notion that it’s arrogant, presumptuous, or rude to ask questions and raise concerns.

- Spend board meeting time mostly rubber-stamping or listening to reports without discussion.

Effective boards exercise leading accountability, not lagging accountability.

- Discuss the same metrics over time to identify patterns and trends, and home in on how and why key metrics are off track.

- Identify concerns as early as possible.

DON’T:

- Look at isolated and unconnected snapshots of data from meeting to meeting, missing patterns and trends.

Effective boards set expectations for attendance and engagement, and uphold them.

DO:

- Routinely show up for board and committee meetings without extra reminders, treating them as can’t-miss calendar commitments, making extra effort to attend, and missing only when absolutely necessary.

- Inform others in advance about unavoidable missed meetings and provide a proxy vote (if bylaws allow).

DON’T:

- Have board members who lack the time to engage.

- Tolerate a degraded board culture (e.g., at times, not enough board members show up to hit quorum; school leaders are often embarrassed and frustrated).

- Let a few people do almost all the work; they often develop resentment and leave the board.

Effective boards communicate regularly, collegially, and responsively among board members and with leadership.

DO:

- Check in as appropriate — not too often, not too infrequently.

- Report back in a timely manner on work they committed to do.

- Share ideas, concerns, questions, and gratitude professionally and concisely.

- Respond to board colleagues or school staff with the responsiveness they bring to work communication.

DON’T:

- Drop the ball.

- Assume it’s fine to skip reading board-related emails, board meeting materials, authorizer communication, or school leader updates.

Effective boards include the array of lived and professional experience and perspectives the school needs to reach its goals.

DO:

- Maintain a strategic board composition matrix, seeking new board members with needed experience as the organization’s goals evolve.

- Recruit new members thoughtfully and in alignment with goals.

- Honor board terms.

- Offboard disengaged board members.

DON’T:

- Leave essential experience and perspective off the board, such as:

- C-suite leadership experience.

- Human resources experience.

- Legal experience.

- Finance experience relevant to a multimillion dollar nonprofit.

- Genuine connection to the school community.

Effective board members visit the school relatively often, while students and staff are there.

DO:

- Come for special events, but also on ordinary school days.

- Know and follow policies about communicating with staff, parents, and students.

- Coordinate site visits with school leadership in advance.

- Engage with members of the school community through open meetings, town halls, and other appropriate forums.

DON’T:

- Visit the school unannounced.

Effective boards understand that they hold the charter, what the charter requires, and how to monitor.

DO:

- Read the charter agreement and understand the goals and outcome expectations.

- Know who authorizes the school and how that authorizer works, including the opportunities and/or requirements for board members to meet directly with authorizer staff or board members.

- Understand the timeline and criteria for charter renewal.

DON’T:

- Fail to truly understand the nature of a public charter school.

- Avoid interacting with the authorizer, skip reading authorizer communications, or miss authorizer meetings or trainings.

Effective boards evaluate the school leader professionally.

DO:

- Invest in developing a sound evaluation process.

- Have board members with experience in performance management, leadership, and evaluation.

- Thoughtfully seek feedback from direct reports, all board members, and other key stakeholders on school leader performance.

DON’T:

- Ignore or avoid school leader evaluation, or substitute a casual conversation.

- Fail to set annual compensation, update contracts in a timely manner, etc.

Effective boards seek information and support from a range of sources.

- Seek high-quality training, best-practice governance resources, and clarity about their role from trusted experts.

- Access information on the website of the authorizer and charter support organizations about school performance, compliance requirements, accountability changes, and peer schools.

- Work with leadership staff in board committees.

DON’T:

- Get all information about school performance and board responsibilities only from the school leader.

Effective boards approach board work with curiosity, a problem-solving approach, and an unyielding focus on achieving high outcomes for students.

DO:

- Bring a curiosity mindset to board work, phrasing almost all comments as questions.

- Learn enough about the school’s strategy to ask good questions regarding progress toward goals.

- Contribute their experience and leadership toward helping the school achieve its goals.

- Bring up uncomfortable topics if necessary, using data to drive the discussion.

- Engage in problem-solving with leadership staff, balancing humility with a steady focus on achieving goals.

DON’T:

- Leave personal judgment and insights at the door out of fear of micromanaging or overstepping.

- Be passive, hands-off, and relieved when leadership “handles” everything, including scheduling, preparing agendas, and creating and sending board materials.

Effective boards lead with a supportive style.

- Balance empathy, understanding, compassion, and care with a focus on results and improvement.

DON’T:

- Threaten, shame, pester, demean, or belittle school staff.

Effective boards speak with one voice.

DO:

- Encourage and sustain robust and rich discussions within the board, and then present as a unified and cohesive group.

DON’T:

- Maintain personal agendas, hold disagreement, cultivate factions.

Effective boards get better every year.

- Participate honestly in a board self-assessment survey every year, understand opportunities for improvement, and personally commit to doing better.

DON’T:

- Ignore ways in which the board is falling short.

- Tolerate and maintain a board culture that is insufficient.

Start with the basics.

Great board members understand and commit to the role.

Every member of a good board should approach this work with the seriousness and attentiveness it merits. While board service isn’t a full-time or paid job, it merits the same level of professionalism and intentionality. You would be surprised at how many board members we meet who know very little about the school they are responsible for governing. Every member of an effective board should know these basics about the school pretty much off the top of their head:

- The school’s mission.

- How many students the school serves, and will serve at full capacity.

- How the school/network is structured, including positions on its leadership team.

- Roughly how many teachers work at the school.

- The school’s top-line budget.

- The school’s performance on the metrics the authorizer uses to determine good standing.

- The terms of the charter: when the school is up for renewal and the metrics it must achieve in order to be renewed.

- The other board members.

Don’t be this board.

In Bellwether’s experience working with boards, we see some common archetypes of boards that think they are doing a good job, and in some ways are, but are not fulfilling the serious responsibilities of a governing board. These include:

The fundraising-only board.

- Many board members are high-influence leaders, funders, and donors who may not spend much time on board work.

- School staff spends a lot of time staffing the board to maximize financial support and minimize time for board members.

- The board tends to meet infrequently, committees even less so, and activity other than fundraising is minimal; the board is generally only lightly engaged with the daily, weekly, and monthly work of governance.

- These boards feel more like “traditional” nonprofit boards, prioritizing the ability to give resources without active engagement in overseeing progress toward goals.

The friends-and-family board.

- Virtually all board members are recruited from the network of the school’s founder, current leader, and/or current board members.

- Has the feel of a social group, not a professional, independent governing board.

- Tends to avoid tough conversations about accountability.

The all- or mostly-parents board.

- All-parent boards often struggle to find the necessary altitude for a governing board (although having some current parents on a board is encouraged and, in some states, required).

- Parent-only boards often have the feel of a PTA, which serves an essential purpose in a school but not the same purpose as a governing board.

- Members of the board often tend to overweight the opinions and experiences of their friends in the parent community.

The disengaged board.

- Allows the staff to do 90% of the work of the board.

- Barely meets quorums, keeps meetings short, and spends most of the time on compliance-related work.

The “rubber stamp” board.

- Believes its job is to approve whatever the leader puts before the board; they don’t want to upset the leader, insult them, or risk having them leave the job. They are effusively positive and complimentary.

- Tends to feel that any oversight will be seen as unsupportive or intrusive; rarely asks hard questions or probes for more information on complicated issues.

The micromanaging board.

- Wants too many details, asks many irrelevant questions, and makes burdensome and off-topic requests for information or explanation.

- Thinks it knows better than school leadership and that the staff’s job is to execute the board’s priorities and ideas.

- Advances board members’ personal agendas.

So, what do great boards do? This playbook is designed to get helpful and easy-to-use information to charter school board members and school leaders, so you can spend more time on the issues that matter most for your students.

A Note on Board Structure

While charter schools are typically 501(c)(3) nonprofits, they are notably different from most nonprofit organizations, due to the scale of public funding, the unique relationship schools have with their community, the role of authorizers, and the public nature of accountability.

Governance Is Accountability

KEY QUESTIONS FOR BOARD MEMBERS:

- Do you know the three to five most important strategic goals for the school/network this year?

- Do you know how to measure whether the school is on track to achieve those goals?

- Do you know the key risks that could prevent the school from achieving these goals?

- Do you know if the school is meeting state and authorizer accountability metrics?

- Would you recommend this school to a friend or family member?

Effective governance is, at its core, all about accountability.

The job of charter school authorizers is to hold schools accountable to the terms of the charter contract. If a school is not fulfilling the goals and student achievement expectations, the school can be warned, face requirements and mandates for improvement, or face charter revocation. However, authorizers exercise a lagging accountability. By the time an authorizer raises concerns, a school’s or network’s problems are often deep, entrenched, and sometimes intractable. Boards, on the other hand, have the opportunity and responsibility to exercise leading accountability — in real time.

“In Hospitals, Board Rooms Are as Important as Operating Rooms”

“Several studies show that hospital boards can improve quality and can make decisions associated with reduced mortality rates. But not all boards do so…. [Most board members] don’t think it’s their job to hold management accountable for performance. Board members often feel like clinical quality is physicians’ jobs, and they don’t want to step on doctors’ toes…

‘I’m a much better doctor in a well-managed hospital where the systems are in place to help me do my best work,’ [said one doctor interviewed]. ‘Even a great chef can’t produce a good omelet with eggs that are stored in the freezer or [with a] stove [that] doesn’t work reliably.'”

Source: Austin Frakt, “In Hospitals, Board Rooms Are as Important as Operating Rooms,” The New York Times, February 16, 2015.

School- or network-level boards can identify problems early, track patterns and trends as they emerge, and notice as soon as progress toward goals slows, stalls, or never happens. This is the real value of having school-level boards: Boards can help school leaders shift strategy, change course, adjust tactics, and resolve small issues before they become big problems. Almost all problems and struggles that threaten the success of a charter school are evident long before they become insurmountable. Boards can act when they see early indicators of trouble, rather than react once the school is struggling.

Turning around persistently low-performing schools is notoriously difficult, and sustaining low-performing schools is exactly what the charter sector promised not to do. It’s up to every board to monitor academic and financial performance, think carefully and consistently about the future sustainability of the organization, and recognize when it is time to consider a different plan — and not wait (often years) for the authorizer to weigh in.

Why don’t boards do this?

Many boards waver on accountability. It can be hard. It often doesn’t feel good, comfortable, or frankly nice. It takes (a lot of) time and energy. It might require stepping outside of both the comfort zone and professional expertise of board members. Many board members prefer to come from a place of humility and respect for school leadership, and feel that holding the leader accountable is inconsistent with that.

In addition to authorizer measures, there are resources that boards can consult to know when to be concerned, such as the Indicators of Distress research as a way for boards to have context for the data they see.

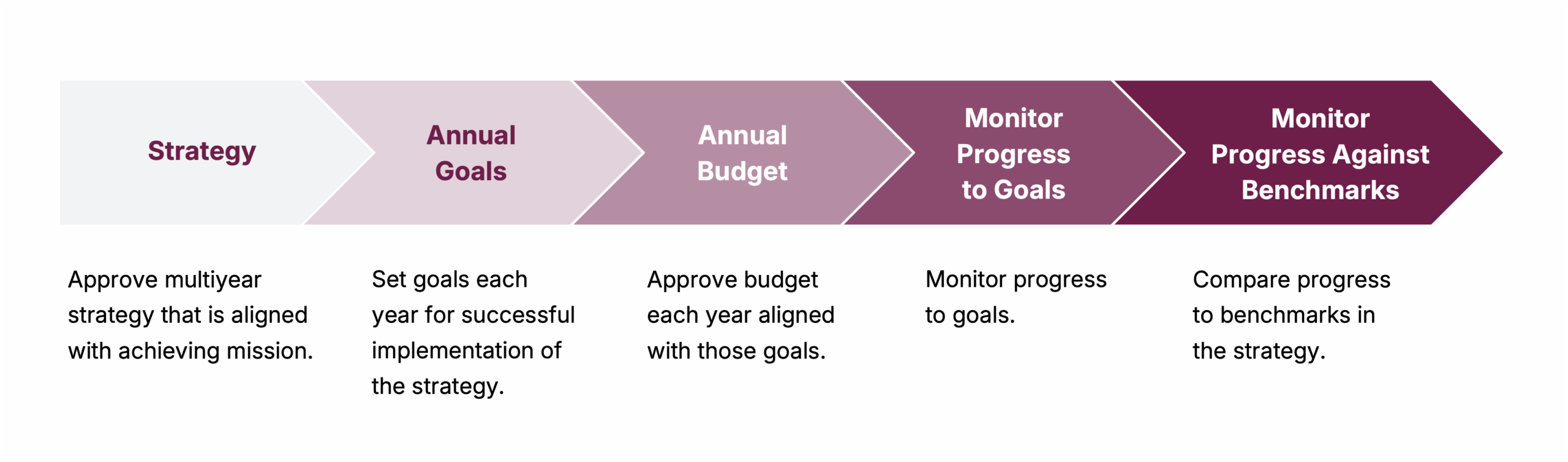

Accountability starts with strategy and goals.

A board and a charter school leader must align on the three to five most important goals for the school each year. Many boards skip over this essential work. Without clarity about and alignment around goals, governance is rudderless. Boards must know the school’s high bar for success (mission), how school leadership plans to get to that bar (strategy), and how to measure progress (goals + metrics).

Every board member should be able to name the goals that must be achieved each year for the school to provide a high-quality education. This clarity and alignment are best achieved through a thoughtful strategic planning process every three to five years. It’s almost impossible for boards to exercise meaningful accountability without a multiyear strategic plan that clearly lays out, based on context, landscape, and current school performance, what school leadership will do to improve school quality and sustainability, with benchmarks to measure progress.

The board and school leader then develop annual goals for academic, financial, and operational performance aligned with the strategic plan. Throughout the year, in every committee meeting and board meeting, the board monitors progress towards those goals, using the agreed-upon metrics. This is what accountability looks like in practice.

The best way for boards to exercise this kind of data-informed accountability is to develop, update, and regularly review a dashboard in partnership with the school’s leadership team. The dashboard must:

- Include key academic, financial, and operational goals and the metrics that will be tracked to measure progress toward annual and multiyear goals.

- Update those metrics at regular intervals throughout the school year.

- Indicate important benchmarks organizational sustainability and success, informed by the authorizer framework, metrics set by other stakeholders, and internal school goals.

The dashboard should be structured to make it easy for the board to:

- Track progress toward each key goal and whether the school is on track to achieve the goal.

- Notice when any important benchmark is missed and flag concerns right away.

- Track patterns and trends over time.

- Know how other schools in the city and state are doing.

- Understand the significance of both “on-track” and “off-track” patterns.

Note that it’s hard work to set appropriate goals. Annual goals should be ambitious yet feasible, realistic and stretch, concrete but nuanced. Resource constraints matter but cannot be used as an excuse. Not all goals are quantitative, but progress needs to be measurable.

In addition, anecdotes are not data. We love to see boards hear stories of success, examples of the mission in action, and high points. But, effective governance is fueled by data, not stories, and governance by anecdote rarely leads to the right decisions.

TOOLS, TEMPLATES, AND RESOURCES

- Board Dashboard — An essential tool for boards and school leaders to track key metrics across a school’s identity, academics, student culture, talent, leadership, engagement, governance, operations, and finance.

- Board Tracker — A resource for boards to plan the work for each year, oriented around the annual goals, for the full board and each committee. This tracker comes pre-populated with suggested board and committee activities for each month based on what effective boards do; this is meant as a starting point for boards to adapt and adjust.

- Good Board Questions — Suggested questions for board members to ask in tricky or difficult situations.

Boards Must Ensure Students Are Learning

KEY QUESTIONS FOR BOARD MEMBERS:

- Are the school’s students meeting or exceeding grade-level expectations?

- Is student academic performance growing at or above the expected rate?

- Are there differences between groups of students?

- Is school leadership ensuring high-quality instructional materials and accompanying training for teachers are available?

- Are resources — including money and time — allocated toward improving student proficiency and growth?

Effective boards track progress toward high expectations for all students.

Think about a time you were part of a team that won. Any kind of team – sports, workplace, academic. In all likelihood, that team won because all teammates shared a clear sense of what you wanted to achieve, you worked together to achieve it, you allocated roles based on each teammate’s strengths, you measured your progress along the way, and you made big and small adjustments to stay on track to the goal. Every board is a team, and that team mentality is a great way to think about governance.

The most important job of a school is to provide an excellent education that ensures that students gain the skills, knowledge, and experiences that will equip them to thrive. Effective boards partner with school leadership to set strategic direction and clear goals for student success, and then consistently monitor progress toward those goals. When the school is not on track to meet its strategic goals for students, board members must dial up support and oversight, not dial back expectations. They cannot be passive, reactive, or complacent.

Every member of an effective board knows the most important metrics of student success. This starts with knowing the state’s/authorizer’s accountability targets/standards, which the board is required to measure. Generally, however, the authorizer’s metrics are the minimum, not the maximum. Boards need to understand the key factors that influence whether students in the school are thriving, as outlined in a strong strategic plan.

Once the board clearly understands the academic goals, effective boards monitor the agreed-upon metrics consistently throughout each year in alignment with the school’s broader strategic plan and dashboard — all with an eye on student outcomes, well-being, and success. To do this, boards need:

- Discipline: At the outset of every school year, board members should be clear about the school’s key goals and what metrics they will monitor for each goal, and track progress toward those goals consistently.

- Information: Board members need regular updates on these key indicators from school staff, as well as annual information from the authorizer each summer/early fall.

- Courage: If the school is off track on one or more of those key indicators, the board must notice and take action.

This work is led by the academic committee of the board. At the beginning of each school year, the academic committee should set benchmarks for both current-year and longer-term student academic outcomes, and at every committee meeting, monitor whether the school is on or off track to meet those benchmarks. If one or more of these benchmarks is not hit, the committee should raise a red flag, as these are early indicators of distress that require board attention.

The job of the academic committee is to understand why (and which) students are not on track, provide needed support, offer guidance and encouragement to leadership, and continue to track data to ensure that challenges are addressed. While not every board member will have school or instructional expertise, all board members can bring experience from different sectors with monitoring progress toward clearly stated objectives and measures.

Some advice based on our experience working with hundreds of boards:

Vision statements like “every child in this school will lead a thriving life” are not goals.

- Goals must be clear and measurable.

- Goals should cover the key drivers of improved student learning: improving instruction, using high-quality curricula, following a strategic plan, and closing achievement gaps.

Get the dashboard right.

- This is always harder than it feels like it should be, but every board needs to put in the work to create a dashboard that includes the goals and all key metrics to measure progress toward student learning/success goals.

- Understand when high-stakes data are available from the authorizer, state, etc.

- The full board, not just members of the academic committee, needs to understand the data in the dashboard.

Trust and verify data.

- Academic committee members should regularly check the authorizer’s website along with the websites of other organizations that share statewide/citywide school performance data.

- Board members must ask questions about the data shared by staff members in committee meetings.

Measure both growth and proficiency — and know the difference.

- This conversation should happen within the academic committee every year.

Not everyone needs to be an expert in academics or education.

- While it is essential to have a few people on the board who are familiar with schools, other members with experience in a range of fields are poised to measure success on an organization’s most important goals, monitor follow-through on a course of action, and maintain accountability for results.

- Bringing business, operational, and finance acumen and discipline to a charter school board is extremely valuable, and underscores why boards should seek members with a range of professional experience.

- The academic committee should include people with experience in education and understanding student data.

TOOLS, TEMPLATES, AND RESOURCES

- Academic Committee Responsibilities and Workplan — An overview of the role of the academic committee, with a template the committee can use to build its workplan for the school year, pre-populated with suggested actions for each month as a starting point.

The Financial Sustainability of the School Is the Board’s Responsibility

KEY QUESTIONS FOR BOARD MEMBERS:

- Are resources allocated in line with the strategic plan and financial sustainability?

- Does the board track financial performance on the annual budget throughout the year?

- Does the school have a viable financial model for long-term sustainability?

- Does the board follow through on all findings in the annual audit?

Boards must ensure that resources are allocated toward student success and school sustainability.

A charter school or network is a multimillion-dollar (in some cases, hundreds of millions) organization. No matter how good the academic program or school culture, if the organization doesn’t plan for the future and invest in sustainability, the school will not survive. A charter school isn’t meant to be a shooting star — a good idea that runs its course when the founder leaves. A school is meant to be an enduring community organization, offering a high-quality educational option that families can count on. Ultimately, this is the board’s responsibility.

Every charter school’s board is responsible for the financial sustainability and operational soundness of the organization. This involves:

- Approving a budget each year that allocates resources in accordance with annual goals for school and student success.

- Monitoring financial management toward that budget.

- Conducting an annual audit and taking appropriate actions based on its findings.

- Understanding whether the school’s financial model will lead to long-term viability.

- Identifying and mitigating financial and operational risks to the school’s success.

For a school to set a course to sustainability, the board and leadership must work together consistently to navigate the present and plan for the future by:

- Ensuring that a sound business plan and solid multiyear financial model are in place.

- Tracking enrollment, hiring, and funding projections.

- Understanding current and emerging market trends and competition.

- Managing current and projected staff compensation and talent pipeline.

- Proactively identifying and mitigating threats to the organization.

When it comes to financial oversight and sustainability, boards must rely on leading indicators of success or distress, not lagging. Too many boards look at snapshots of static or isolated data points, rather than patterns that give a clear picture of performance. Boards should look at the same data annually, measuring the same key strategic priorities each year, and develop a dynamic picture of performance over time.

Once the board approves the school’s budget each year, the finance committee tracks key metrics of financial and operational health, including:

- Cash on hand

- Operating deficits

- Debt-to-asset ratio

- Audit findings and follow-ups

- Enrollment trends

The finance committee should then set benchmarks for both current-year and longer-term financial health, and at every committee meeting, monitor whether the school is on or off track to meet those benchmarks. If one or more of these benchmarks is not hit, the committee should raise a red flag, as these are early indicators of distress that require board attention. These might include:

- Full enrollment by a given date and associated metrics of progress (50% enrollment by X date, 75% enrollment by Y date, # new students enrolled, etc.).

- Cash on hand at all times.

- Payroll on track with budget allocations.

- Changes in facilities financing or other real estate related transactions.

- Meeting debt service milestones.

(Note: For schools that are scaling up to serve more students, these metrics should be tracked separately for current campus/grade levels and new campus/grade levels to understand progress of growth planning.)

TOOLS, TEMPLATES, AND RESOURCES

- Finance Committee Responsibilities and Workplan — An overview of the role of the finance committee, with a template the committee can use to build its workplan for the school year, pre-populated with suggested actions for each month as a starting point.

Boards Ensure the School Has an Effective Leader

KEY QUESTIONS FOR BOARD MEMBERS:

- Do you know what excellent leadership for your school or network looks like? Do you have an updated job description for your school leader, and a set of relevant leadership competencies?

- Does the board evaluate the leader every year?

- Is the board clear on how to support the leader in achieving goals and overcoming challenges?

- Does the leader have a highly effective leadership team supporting progress toward those goals?

- Is the school leader improving their performance in the role year over year? How do you know?

- Are you prepared for leader succession?

Every charter school needs a strong school leader. This is the board’s responsibility.

Every charter school needs a strong leader at the helm to achieve its mission, accelerate student achievement, hire and develop great teachers, and lead the organization to long-term sustainability. This is perhaps the most important factor for a successful school, and this is one of the most important roles of a charter school board. Boards are responsible for hiring a qualified and experienced school leader, and then for playing all the roles a manager plays in a workplace, including:

- Supporting that leader with substantive thought partnership, problem-solving, and strategic insights.

- Monitoring and evaluating the leader’s performance, updating job description and competencies each year.

- Investing in the leader’s development and improvement.

- Recognizing the leader’s success.

- Compensating the leader fairly.

- Preparing for leader succession well before it happens, including both emergency succession and planned departure.

Almost every board we know wants to do their best to support the school leader, but most boards struggle to play all these roles well. Most boards want to support the school leader. They recognize how hard that person works on behalf of students, teachers, and families, and they want the person to stay in the job. But boards that support without also holding leaders accountable are doing only half their job, and these boards miss signs of trouble all the time. They also miss opportunities to be supportive in ways that are actually helpful to the leader.

The relationship between the board and the leader is a formal and professional relationship. The dynamic should not be casual, chummy, or unstructured. While personal “fit” and closeness are often important features of the board-school leader relationship, they cannot be the primary nature of the relationship. The board should be a critical friend, not just a supportive friend, to the school leader — that “tough friend” who sometimes says the hard thing you don’t want to hear, even though you know they’re probably right.

The board governs; the school leader manages.

We get asked all the time how boards can better balance governance and management, or “stay in the governance lane.” The truth is, everything in this playbook is intended to define what governance is in practice. There is no magic wand to calibrate the balance of governance and management within each organization. Finding that balance requires ongoing honest conversations between the board and the school leader to continue to clarify the roles of each and hold each other accountable for everything laid out throughout this playbook.

These conversations can be hard, and we recommend finding structures and templates that work for you. One template we like to align on to strike the right balance between the board and the school leader is below.

It’s surprisingly hard to maintain the right balance in the board-school leader relationship.

- Leaders don’t want boards that are too hands-on, but boards that are too hands-off don’t know enough to be helpful at all.

- Leaders appreciate getting good ideas and advice from experienced and knowledgeable board members, but they don’t want to hear off-topic, ill-informed, or irrelevant suggestions.

- Leaders know that the more informed board members are, the more likely they are to give good input, but it takes a lot of time to keep board members updated, and they worry that too much information opens the door to micromanagement.

We often hear well-meaning board members say to school leaders, “We’re here if you need us.” This is lovely … and passive. School leaders need board members who are in the work with them, standing alongside them, not just behind them. School leaders need board members who are in the work with them, standing beside them, not just behind them. We encourage board members to instead ask how to help, listen carefully to the leader’s requests and respond specifically, and request feedback on whether what they do is, in fact, helpful. For example, board members can ask:

- “We understand that it would be helpful to you if we attended training/spent more time preparing for board meetings/prioritized committee meeting participation/attended fundraising events. We are planning to do X by Y date. Would that be helpful?”

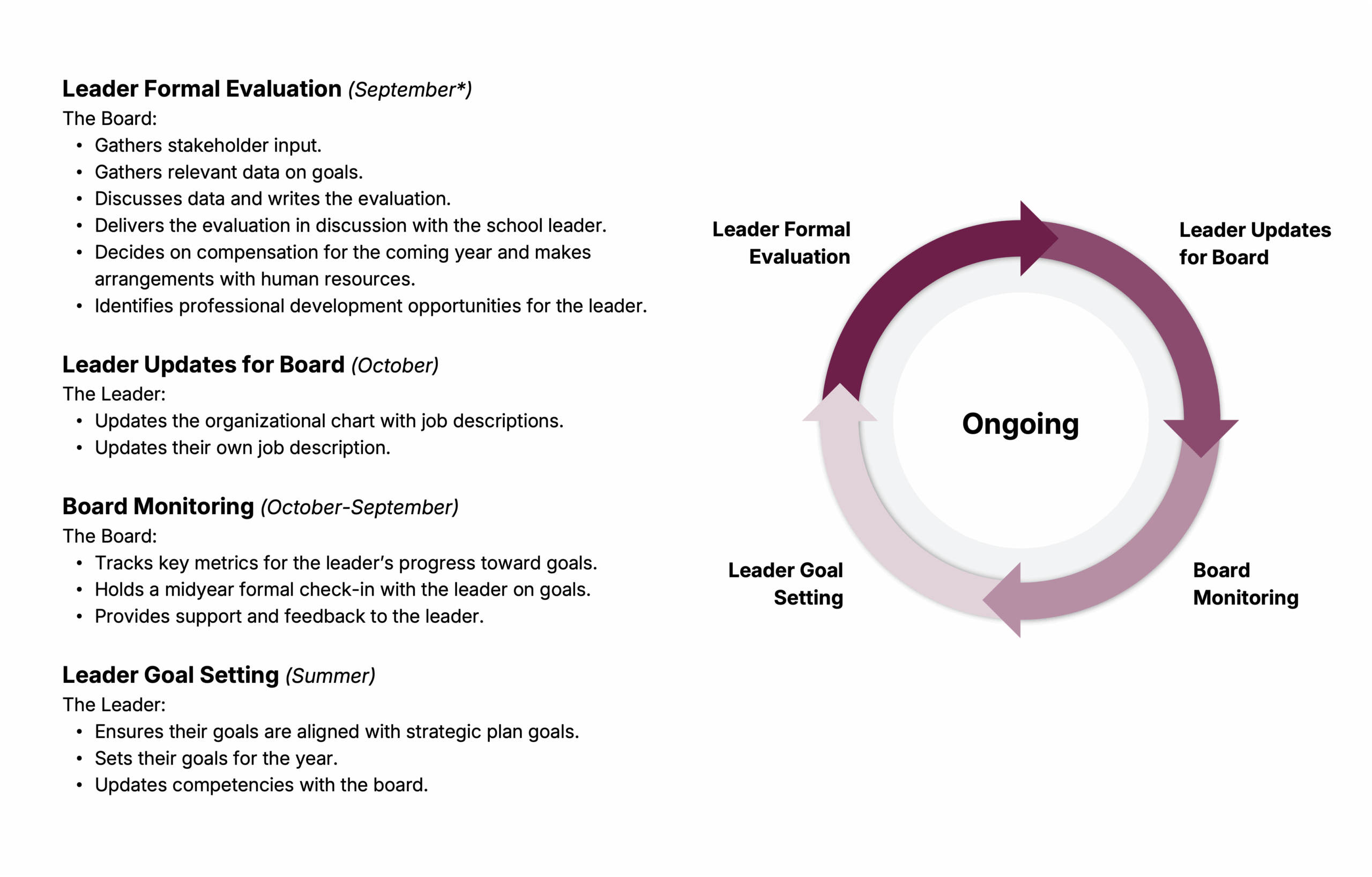

To lead the ongoing work of nurturing this balanced, complex relationship, every board should establish a school leader support and evaluation committee composed of two board members.

The school leader support and evaluation committee:

- Leads the board’s collaboration with the school leader throughout the year.

- Ensures that the board and leader align on the three to five most important strategic goals at the beginning of each school year and on the metrics the board will track to measure progress.

- Leads the evaluation of the school leader, including midyear check-in, data gathering, and annual formal evaluation.

- Check-ins should be organized around monitoring progress toward goals.

- Evaluation should be structured and comprehensive.

- Feedback should be accurate and honest, positive and constructive.

- Works with the school leader to update the following every year:

- The school leader’s annual goals, tied to the school’s mission and aligned with its multiyear strategic plan.

- The competencies the board expects the leader to demonstrate.

- The school leader’s job description, to help the board understand the leader’s responsibilities, including how they allocate their time and how their role has evolved.

- An organizational chart and high-level job descriptions for leadership staff, to inform the board’s understanding of how well the leader hires, delegates, and supports their direct reports.

- Internal leadership capacity, instructional quality, and leadership’s assessment of risks.

In our experience, boards generally want to support the school leader but may not know how.

School leaders who feel supported by their boards tell us that:

- The board and the school leader have a high-trust relationship grounded in progress toward metrics of success and sustainability.

- The board chair and school leader meet either weekly or biweekly; in these meetings/calls, they quickly discuss the key strategic priorities and touch on updates, emerging issues, needs for support, successes to celebrate, etc.

- An agenda template is here.

- Communication preferences and norms are developed for each new board chair/school leader.

- Text? Email? Something else?

- Are after-hours communications OK?

- Weekly/biweekly meetings follow a running agenda with set time limits.

- Board members and leadership staff work together in regular committee meetings to review and discuss data aligned with key strategic priorities.

- The board chair and school leader meet either weekly or biweekly; in these meetings/calls, they quickly discuss the key strategic priorities and touch on updates, emerging issues, needs for support, successes to celebrate, etc.

- The board supports the leader’s success in the role by investing in their ongoing professional development, frequently demonstrating support and appreciation for the challenges of the job privately and publicly, and responding to requests for support.

- Boards encourage the school leader to bring performance-related professional development opportunities to the board.

- The board emails school staff and parents at least once a semester with an update expressing support for the leader.

- The board finds small ways to show appreciation and recognition for the school leader throughout the school year.

- Birthday/job anniversary texts.

- Flowers or treats.

- Text after something notable (good or bad) happens.

- The board is clear, candid, and courageous in its feedback.

- Effective boards give the school leader clear feedback on performance, aligned with the agreed-upon goals and structured around data and metrics.

Bellwether has found the following guidance to be helpful for board-school leader relationships:

- Ask how the school leader is doing, what keeps them up at night, what gets them up in the morning, and how they feel about the board.

- Embrace candor; make it clear that the board needs to see all data, not just good data.

- React calmly when problems arise and approach with support and resolve; don’t back down from addressing challenges.

- Show support to the school leadership team as well as the school leader.

- Know their names and what their jobs entail.

- Get to know leadership team members through committee meetings.

- Ask what kinds of board supports are helpful in board meetings and committee meetings.

- Give them space in board meetings to step out of the day-to-day and think big picture. This is one of the best ways a board can support the school leader.

- Know what “big bets” — changes, innovations, overhauls — would best serve the school’s students, and be enthusiastic champions of those big bets.

- Ask thoughtful questions that open up different ways of thinking about challenges and opportunities.

Strong boards offer a professional, helpful, and rigorous annual evaluation of school leaders.

Every school leader deserves, and every board is responsible for conducting, a professional annual evaluation that includes input from direct reports, feedback on core leadership competencies, recognition of accomplishments, and constructive feedback for growth. Yet too many school leaders have never been given a “real” evaluation by their boards. Many get no evaluation at all, and others just have an informal conversation with the board chair.

One of the most important ways a board can support and retain a strong leader is by evaluating their performance through a formal annual evaluation that incorporates feedback from staff and key stakeholders, measures performance against goals and demonstration of competencies, and delivers actionable feedback to the school leader. Boards that do an effective job at leader evaluation increase the chances that high-performing school leaders stay longer in their jobs, which is pivotal in improving student success.

Note: *The school leader evaluation cycle should be driven by when data from the previous academic year is available.

Why do so many boards shy away from effectively evaluating the leader who reports to them?

- Evaluation can feel negative, punitive, or even threatening to school leaders, who might fear for their job security, lack trust in the board, or wonder whether board members really understand their jobs.

- Many boards are not well-equipped to conduct an evaluation; they may not have members with experience in performance evaluation, executive/school leadership, or human resources. Boards also often lack training on and capacity for leader evaluation. Given the sensitive nature of performance evaluation, they may not know how to design good survey questions, have experience handling varying feedback, or want to involve the school’s human resources director.

- It is hard for boards to accurately assess leader performance without fully understanding the nuances and demands of the complicated job of leading a school. Most boards don’t have updated job descriptions and benchmarks for strong performance for the school leader position, and thus the evaluation happens in somewhat of a vacuum.

- Many board members feel they themselves don’t have enough insight to fairly assess performance, and they sometimes also inaccurately interpret feedback from direct reports — they mistake anecdotes for data, overweight outlier feedback, mischaracterize input from staff and parents, and/or entirely miss key aspects of context that impact performance.

- Many boards don’t realize they are responsible for setting compensation for the school leader each year and working with the human resources function in the school/network to manage compensation increases.

Boards must always be prepared for school leader succession.

It’s the responsibility of the board to make sure the school has a strong leader in place at all times. We generally recommend that boards invest time and energy into keeping their current leader if that leader is effective, as school leader transitions are challenging, time-consuming, and usually disruptive. However, leader transitions are inevitable, and many boards don’t lay the groundwork for successful and smooth transitions.

Succession planning isn’t just writing out a plan and then shelving it until you need it. The steps boards need to take to be prepared for succession are part of the year-in, year-out work of being an engaged, effective board. To be prepared at all times for eventual leader succession, we recommend that boards:

Be a great board.

Know how the organization functions.

Our succession planning template supports boards to better understand what knowledge and information they need to have and capture it in one place. This helps an emergency transition go smoothly, and can ensure that the board knows enough about the role to hire the right new leader. It also minimizes the risk of too much institutional knowledge living only in the school leader’s head. This includes:

- An updated job description for the leader

- An updated organizational chart, with job descriptions for leadership team

- Key operations and financial information

- Contact information for key staff and outside contacts

Have an emergency succession plan in place at all times.

- Have an emergency succession plan in place at all times to ensure that someone with training, knowledge, and experience will be available to lead and manage the school if the school leader is unexpectedly unable to perform their job (either because they depart without notice or need an immediate leave of absence). This plan must articulate:

- Who the interim leader will be.

- What support they need now to be ready.

- Who will take over their current job.

- How the school’s day-to-day operations will be maintained without disruption.

- Who will take over financial management.

- Who will handle communications, including developing messaging, sharing information, and deciding which stakeholders need what information and how they will get it.

Discuss the school leader’s long-term plans.

- Leverage a search firm for access to resources and networks, and complement/tailor with strong board support and knowledge of the needs/context of the school.

- Be deliberate about engaging staff and the school community and communicate updates regularly.

- Approach internal candidates and interim leaders thoughtfully.

- Consider what role the outgoing leader can or should play in the search and transition process, and note that this may depend on the context and if it is a founding leader.

- Develop a robust onboarding plan and allow the new leader ample time to transition.

TOOLS, TEMPLATES, AND RESOURCES

- School Leader Support and Evaluation Committee Responsibilities and Workplan — An overview of the role of the school leader support and evaluation committee, with a template the committee can use to build its workplan for the school year, pre-populated with suggested actions for each month as a starting point.

- School Leader Evaluation Overview — An overview of the process, timeline, and components of the school leader evaluation.

- School Leader Evaluation Checklist — A list of suggested sources of insight, survey components, and school leader competencies to include in the school leader evaluation.

- School Leader Succession Planning Template — A template that boards can use to gather and update key information to prepare for school leader succession.

- Board Chair and School Leader Meeting Agenda Template — An agenda template that board chairs and school leaders can use for their weekly/biweekly meetings.

Great Boards Prioritize Effective Governance Structures, Processes, and Practices

KEY QUESTIONS FOR BOARD MEMBERS:

- Do meetings start and end on time, and feel like a great use of time?

- Are all board members consistently engaged, informed, and motivated?

- Are board and committee discussions energetic, robust, data-driven, and important?

- Do board members bring a range of lived and professional experiences to the table?

- Does your board run a tight ship, with clear structures and practices that feel professional, cohesive, and coherent?

Too many boards are much too loose, and that looseness puts schools at risk, prevents boards from being as helpful and supportive as they could be, and limits the effectiveness of board oversight.

Does any of this sound familiar?

- ”We don’t need committees; it takes too much time, and we’re fine.”

- “No one on the board has time to learn how to use a portal or Google Drive.”

- “No, we don’t look at our bylaws; I’m sure we’re fine.”

- “Truthfully, a few people do all the work, but I don’t think they mind.”

- “We have had the same board chair since the school was founded 18 years ago. In fact, most of our board members have been on the board for at least 10 years. We can’t let the institutional memory go.”

Solid governance infrastructure is not optional, and it is not pick-and-choose.

Sound governance practices, processes, and structures are the nonnegotiable infrastructure of effective governance, legal compliance, consistent board member engagement, and steady leadership on strategy and accountability. Boards that don’t function with this infrastructure in place are putting their schools at risk. We know from working with hundreds of boards that the better the infrastructure, the better the experience for board members, value for school leaders, and odds of success for the school.

Charter school leaders and board members should not waste time debating the finer points of governance and reinventing the wheel. Students and staff need the board to focus on the most important strategic issues, not endlessly circle around how to function. This section lays out the essentials of good governance in order to save boards the time of creating them.

This work is led by the governance committee. We believe that for most boards, the governance committee should take the place of the executive committee. The governance committee is responsible for making sure the board functions well; unlike an executive committee, this committee does not have authority to act on behalf of the full board (authority we do not believe should rest with any committee).

Every effective charter school board must have these nonnegotiable structures and practices.

- The board acts in accordance with bylaws, and updates them every three years to reflect evolutions in organizational functioning and context.

- A meaningful set of expectations and norms for board members, captured in a board member agreement, shapes board culture.

- The board has an annual calendar that is always up to date and guides all boardwide and committee work; every board member and leadership staff member knows what they are responsible for updating.

- At least three committees (governance, finance, and academic) meet at least once between board meetings to advance important board work.

- The full board understands the responsibilities of each board officer and committee chair position, and the process for selecting board officers.

- Board composition is aligned with the strategic priorities of the school.

- Board meetings are a great use of time.

- The board conducts an annual self-assessment, highlights areas for improvement, and reports on progress toward improvement.

- The board participates in relevant and context-appropriate trainings regularly, focusing on accountability for school and student success.

You need a great board chair.

A high-functioning board chair is a must for an effective board. The board chair certainly should not be expected to do the lion’s share of the work of the board, but a weak board chair is an almost impossible hurdle for a board to overcome. Great board chairs:

- Act as a critical friend, thought partner, and trusted adviser to the school leader.

- Invest in the relationship to strengthen the leader’s efficacy and the school’s performance.

- Seek and accept feedback without defensiveness to get better in the role.

- Understand that their primary job is to organize the board to ensure that the school is providing an excellent education. They know what a great school is and how to measure it, and they know what a great board does and how to measure that. Board chairs often need extra training and support from sector organizations to understand this.

- Are willing to effectively “run” the board with a steady hand and steadfast leadership — celebrating and recognizing excellent board members, keeping meetings running on time (even if it means cutting off people who want to speak), calling out disengaged or disruptive members, and allocating board time to the most important strategic priorities for school success.

- When board chairs single out exceptional board members and recognize them, board culture improves and other board members up their game.

- When board chairs are willing to have honest, tough conversations with board members who are not doing their job, even going so far as asking them to step down if necessary, board culture improves and other board members up their game.

- Are really, really in it to win it. They understand what role to play and when, they are available to the school leader and other board members, they care about the school, and they go out of their way to stay informed, engaged, and enthusiastic.

- Genuinely respect, trust, and like the school leader — and are willing to say hard things, give difficult feedback, share tough truths, and disagree.

- Want training, support, and advice on how to succeed in the role.

- Know who the next board chair is at all times.

The people on the board make or break the board.

Good governance starts with who’s on the team. Board members bring lived and professional experience that can help school leaders make sound decisions. A school leader cannot be expected to bring deep expertise in financial management, legal matters, human resources, public relations, fundraising, and community organizing in addition to their experience in instruction and school leadership. A strong board has members with experience in these areas who can contribute to discussions and share insights and perspectives from their fields. Collectively, this shared leadership leads to better decision-making — and better outcomes for students.

Board composition must be aligned with the strategic priorities of the school. The governance committee should maintain a board composition matrix aligned with the school’s strategic priorities. The matrix should include what professional and lived experiences can help the board achieve those priorities and a running three-year recruiting arc of priorities, terms, and committee makeup.

(Note: Bellwether’s matrix template includes a list of many kinds of experience and perspectives boards need; each board can prioritize based on the current school goals and board members.)

Overall, we offer the following advice regarding board composition:

- Be strategic, not reactive, about who is on the board.

- If academic improvement is paramount, include multiple people with experience in education, school improvement, student data, and strategy.

- If facilities are at the top of the list, include people with experience in facilities financing, real estate development, capital campaigns, etc.

- If staff quality or turnover are the main challenges, include people with experience leading a large team, human resources and workplace culture, and C-suite leadership roles.

- Be specific about what the board needs.

- “Finance experience” is a very broad category. Does the school’s board need an accountant? Someone who has managed multimillion-dollar budgets? Someone who understands school finance and allocating resources to student success?

- The same holds true for education; a former teacher doesn’t bring the same level of experience and insight as a former school leader, or chief financial officer, or human resources director.

- Be clear, consistent, and professional in how the board finds, interviews, selects, and onboards new members.

Our advice for boards about strategic board composition:

Be strategic, not reactive, about who is on the board.

- If academic improvement is paramount, include multiple people with experience in education, school improvement, student data, and strategy.

- If facilities are at the top of the list, include people with experience in facilities financing, real estate development, capital campaigns, etc.

- If staff quality or turnover are the main challenges, include people with experience leading a large team, human resources and workplace culture, and C-suite leadership roles.

Be specific about what the board needs.

- “Finance experience” is a very broad category. Does the school’s board need an accountant? Someone who has managed multimillion-dollar budgets? Someone who understands school finance and allocating resources to student success?

- The same holds true for education; a former teacher doesn’t bring the same level of experience and insight as a former school leader, or chief financial officer, or human resources director.

Be structured and professional with board member selection.

- Be clear, consistent, and professional in how the board finds, interviews, selects, and onboards new members.

In addition to professional and lived experience, boards should also think about the perspectives, context, and capacity of prospective new members.

- Solve complex problems in different fields and have experience sticking with a long-term strategy for success.

- Show up and are willing to put in the time. While board service is not a full-time job, serving on the board of a charter school is more than an hour here and there. Board members should be able to commit two to four hours most weeks.

- Are willing to act courageously on behalf of children, even if that means disagreeing with or clashing with other board members or stakeholders in the community.

- Work in local companies, large and small, to bring experience running a business, hiring local employees, and paying local taxes.

Onboard new members extensively; investing in new members pays off for years to come.

- Plan for onboarding and calendar the time.

- Ask new members how their onboarding experience was and adjust the plan accordingly.

Each seat on the board is precious. Treat it as such.

- Honor the term limits in board bylaws; membership is not a lifetime appointment.

- While institutional memory is important, so are fresh eyes. Boards that don’t add new members fall into habits and patterns that they don’t even see after a while.

Be mindful of how current parent/caregiver board members are represented.

- Parents on the board can offer insights that other board members can’t, and this can serve as a useful, essential “early warning system” regarding concerns among the school’s parents. That said, no one parent can speak for all parents, and boards should be careful not to assume they can or should.

- In addition to one or two parent/caregiver members, the board should systematically review thoughtfully gathered and representative input from all parents/caregivers.

- Parent board members usually benefit from additional training in addition to the training available to all board members; it is often hard for parents to understand that their role as board members requires them to interpret and analyze the information they have about what goes on in the life of the school through a governance lens.

- Parent board members should not be elected. They should be nominated for the board through the governance committee, with the same process as other board members.

Be disciplined about focusing board member time on tracking progress toward goals.

Board members actually spend a remarkably little amount of time together every year, considering the nature of the decisions boards make. It takes significant time and thought to make sure that every hour board members spend together is time well spent. Most of this time is spent in either board meetings or committee meetings.

How this time is structured, the objectives of each meeting, and the value of this time is primarily the responsibility of the board chair. Time spent in board and committee meetings should be strategic, substantive, and organized around the annual goals. Board chairs plan and lead board meetings, assign board members to committees, and monitor committee engagement.

Effective board meetings require preparation weeks in advance. Strategies for success include:

- Meeting agendas always include three clear objectives for the meeting; the board chair checks in during the last five minutes of the meeting on whether the board achieved those objectives.

- The board chair knows how to facilitate a meeting and stick to the times on the agenda, and also knows when an issue is important enough to make an exception.

- Board meeting agendas prioritize structured, well-facilitated discussions about progress to the key priorities and goals for the year, informed by committee.

- There should be a logical sequence of discussions over the year that lines up with when data is available and when the board needs to make key decisions.

- The board follows an annual calendar to ensure discussions and decisions happen when they need to happen.

- The board secretary keeps a running list of to-dos and follow-ups to share out after the meeting.

- The board completes a quick, three-to-five-question survey at the end of each meeting to ask members if the meeting was a great use of time and moved important work forward.

Every effective board operates with a robust committee structure. Each board committee reviews the section of the dashboard relevant to that committee at every meeting. The job of each committee is to dive more deeply into a set of data around the goals in that committee’s area, discuss any off track metrics, and maintain ongoing discussion of the actions school leadership takes to improve.

Bellwether recommends every board have at least three core committees (governance, finance, and academic), plus a school leader support and evaluation committee. These committees typically meet at least once between board meetings and lead a subset of priority work for the year.

- Each committee has a workplan for the year.

- Committees include both board members and staff members, working together to understand progress toward goals and discuss strategy, challenges, and patterns/trends in the data.

- Committee meetings spend no more than 50% of the time listening to staff reports.

- All full-board discussions and decisions have been discussed in committees first.

| Committee | Examples of Metrics to Track | How to Track |

|---|---|---|

| Academic/School Performance |

|

|

| Finance |

|

Getting board culture right attracts great board members.

A charter school board is not a casual, informal group of people who have come together because they love the school and want to “give back.” The board of a public charter school is a legal entity with legal and fiduciary requirements and responsibilities, stewarding millions of dollars of public funds and holding the education of children in its hands. The culture of the board should reflect that responsibility.

Culture is shaped to a large extent by board expectations and norms, also called a board member agreement or board member job description. These expectations should articulate the responsibilities of every board member and clearly indicate how board members are expected to show up. It’s critical that boards 1) set high expectations for attendance and participation commensurate with the high-stakes nature of board work; and 2) have members who are enthusiastic, energetic, committed to the success of the organization, and prepared to make their board service a priority. In practice, this means:

- The board, led by the governance committee, creates and then annually updates a set of expectations and norms, which become a board member agreement.

- Every board member signs this agreement every year.

- The board chair meets with every member annually to review performance, tracks engagement throughout the year, and recognizes excellent and engaged board members for their service.

- Board members who don’t uphold these expectations and norms are removed from the board.

Culture also depends on relationships. We know that many board members are reluctant or unable to take time to get to know one another through social opportunities outside of board meetings. Board service already takes a lot of time, and asking people to spend more time away from their families or jobs is tough. However, when board members don’t know one another, it is hard to have the kind of robust discussions, disagreements, healthy tensions, and uncomfortable interactions that effective board work often requires. We find that when board members don’t take the time to get to know one another, governance suffers.

TOOLS, TEMPLATES, AND RESOURCES

- Committee Roles and Responsibilities — Descriptions of the committees that every board should have, with sample workplans for each committee.

- Governance Committee Responsibilities and Workplan — An overview of the role of the governance committee, with a template the committee can use to build its workplan for the school year, pre-populated with suggested actions for each month as a starting point.

- Board Calendar — A template of a board annual calendar and workplan, with suggested board and committee work for each month, space for each committee to take meeting notes, and key benchmarks for board work.

- Board Officer Roles and Responsibilities — A set of sample job descriptions for board officers.

- Sample Board Member Agreements — Sample board member agreements, outlining the expectations and norms for every board member.

- Board Composition and Recruitment Tracker — A resource boards can use to track the lived and professional experience and capacity board members have, and gaps in board composition based on current school goals. This tracker also includes resources to support boards with recruiting new board members, including sample interview questions and an onboarding checklist.

- Board Meeting Preparation — A sample board meeting agenda and checklist with owners and timelines for each key activity that should be completed in preparation for board meetings.

- Board Officer and Committee Chair Selection Process — Suggested processes for selecting new board officers and committee chairs.

- Board Self-Assessment Questions — A sample survey that boards can use as a self-assessment.

Great Boards Engage in the School Community and Local Education Sector

This section will offer guidance on how boards can:

- Understand the context within which the school operates.

- Engage with families and staff appropriately.

- Support high-quality school choices for all families in their community.

Board members need to understand the education sector in their city and state.

If you were on the board of a cereal company, it wouldn’t be enough to understand your own company’s products and sales. You would need to know a decent amount about the breakfast industry. What kind of cereal do other companies sell? Do they sell more or less than your company? What else do consumers eat for breakfast? Are they eating more or less cereal than they used to? Why? And you would need some familiarity with the customer base for your products, both current customers and the customers you would like to attract.

The same is true for board members of a public charter school. Too many charter school board members know very little about the context within which their school operates — and within which their school competes for students, teachers, and resources. What other schools are nearby? What grades do they serve? How is their program similar to or different from your school? How are students in those schools doing? Why do parents and students choose to attend (or not attend) your school?

Accountability is the board’s primary job. While we understand that it’s hard for board members to also spend time understanding a school’s external context, that understanding is a vital part of that accountability. Effective board members are connected to the broader education community and understand the context within which their school operates.

It’s impossible for a board to govern effectively without knowing:

- The basics of what public charter schools are — public schools, publicly funded, publicly accountable, open to all students — and who authorizes charter schools.

- The current and projected context for charter schools regarding funding, authorizing, accountability, political support, and policy.

- Charter market share in the city and state (what number and what percentage of students are in charter schools, and how that has changed over time).

- Size, growth, location, and student performance of peer schools, including new schools opening, schools merging/acquiring other schools, and schools getting shut down by the authorizer.

- Emerging economic realities and predictions, including rising costs, stressful facilities situations, market competition from private school choice and other options — all amid the end of a huge influx of federal education funding.

- Demographic projections that impact school enrollment.

- The quality of the authorizer, state charter association, and charter school law in the school’s city and state.

- Trends in staffing and compensation in the city and state.

These factors affect school sustainability, and boards must stay updated to inform their decision-making and oversight.

Building trust among staff and parents is vital to effective governance.

Many charter school parents and staff don’t realize that their school is governed by its own board, not the district school board. Boards often overlook opportunities to help educate parents and staff about the role of a charter school board and introduce themselves. Typically, parents and staff hear from boards primarily when something “big” happens — often a crisis. To build visibility and trust, board members can:

- Be visible and enthusiastic supporters of the school at arts or sporting events, milestones like the first day of school or graduation, and teacher appreciation days, among others.

- Send newsletters or other communications to the school community at least once a semester, if not more often, sharing what the board is working on, introducing board members, and asking for feedback.

- Seek input on important issues in appropriate ways, being proactive about hearing from all families and staff (not just the vocal ones), and learning how to listen without promising anything, contradicting anyone, or undermining school leadership.

Schools must have clear policies in place for how board members should and should not communicate with school staff and families, how complaints and grievances are handled, and how people can bring matters to the school’s attention. Parents, staff, and board members should be trained every year on these policies and they should appear in the parent, staff, and board handbooks. Board members should also have solid knowledge about the school, its program, performance, and pertinent facts to avoid sharing inaccurate, outdated, or misleading information.

Board members can be powerful advocates for wider access to high-quality school choices.

All families deserve excellent schools for their children. If the school in a neighborhood is not strong or does not meet their child’s needs, every parent should have other options, regardless of their income or ZIP code. That is the underlying promise of public charter schools: Money should not be the determining factor in the quality of education available to children.

Board members have a unique opportunity to urge policymakers and regulators/authorizers to take action to clear obstacles for schools, appeal to funders and donors to seek the support schools need, and recruit prospective new board members. Charter school board members see firsthand how hard it is to run a great school and the obstacles school leaders face. They develop compassion and respect for the work that educators do every day in challenging circumstances. They learn what policies, support, authorizing practices, and resources schools need to succeed. This experience equips board members to be extremely effective advocates for what schools need to better serve their students.

Every board member should feel they are part of the broader education sector with a stake in the decisions that policymakers and authorizers make that affect every school, including their own. By using their voices, knowledge, passion, and networks, board members can create more opportunities for high-quality public school options for all families in a community.

TOOLS, TEMPLATES, AND RESOURCES

Coming Soon.

Charter School Boards Need Support and Direction from the Charter Ecosystem

If organizations charged with leading the charter school sector elevate and invest in stronger boards, school quality will increase. Across the sector, charter school authorizers and support organizations have an exciting opportunity to commit to holding boards accountable for exercising oversight.

The constellation of charter school incubators, authorizers, funders, and other support organizations that make the charter sector’s work possible typically invest in and work with school leaders, and for the most part leave it to the school leaders to deal with their boards. This is partly why so many charter schools and networks falter when a strong and charismatic founder leaves the organization. As the charter sector continues to mature and face mounting challenges, its leadership ecosystem has an opportunity to elevate, incentivize, and reward effective boards, because it’s the boards, not, ultimately, school founders or leaders, who own and drive enduring organizational sustainability and impact.

The charter ecosystem can transform how boards see their role by reinforcing that:

- Every school leader reports to their boards, not the other way around.

- Every board holds the charter, and is responsible for holding the school accountable for achieving its mission.

- It is the board’s job to take action as proactively as possible if the school is not fulfilling that mission.

Rarely, if ever, do we see ecosystem organizations communicate directly with the board members or chair, or share key information about the school’s success. This lack of communication effectively creates a game of telephone, where the school leader has to decide what information to share with board members and how. We believe it would help boards govern more effectively if they learn directly from these ecosystem organizations the expectations for the school and the board, where they can go for support, and what effective governance entails. In fact, many board members don’t know what “good” looks like. They may not have the context to know the measures of a great school. They have not been told or trained to regularly review information about school performance and measure that against a standard of school excellence.