Surveying School System Leaders

What They Are Saying About Artificial Intelligence (So Far)

Survey Overview and Methodology

Since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022,1 there has been excitement and speculation about the role generative artificial intelligence (AI) could play in teaching and learning. AI holds the potential to address several of education’s most persistent challenges: differentiating student learning through individualized tutoring and other tools, supporting teacher sustainability and effectiveness, and addressing financial challenges through cost reductions and efficiency.

However, incorporating AI into education requires teachers and school leaders to balance risks. There are risks associated with the tools themselves, as AI tools may provide biased or inaccurate information, and privacy risks if personal information, such as a student’s name or disability status, is shared in a tool. There is also the possibility that students may become dependent on AI, failing to develop critical thinking and writing skills. Or that teachers may over-rely on AI, foregoing opportunities to create meaningful connections with students. And there is the risk that AI tools could exacerbate long-standing inequities if they are used in place of addressing systemic issues like understaffing or underfunding.2

There are also real risks to not incorporating AI in education. Most troubling is that schools may not be preparing students with the AI literacy skills they need to be competitive in an evolving job market.3 Here, too, there are concerns that this risk will play out across schools in ways that exacerbate long-standing inequities.

The education sector is in the early stages of understanding how schools are incorporating AI. Most existing surveys about AI in education explore surface-level questions about the teacher and student knowledge and frequency of using tools.4

Bellwether’s survey fills a gap by exploring early trends in how school system leaders are thinking about incorporating AI, what barriers they face, and what challenges they hope that AI will help solve. Specifically, the survey responses and set of qualitative interviews uncover an emerging set of patterns in the field:

- System leaders are cautiously excited about AI and are using it themselves, but lack a systemwide AI strategy.

- Use of AI to improve teacher efficiency and effectiveness is happening faster than student-facing use of AI.

- Many school systems are waiting to adopt an AI policy; where policies exist, they tend to be vague and offer limited guidance for administrators, teachers, or students.

- System leaders are focused on preparing students to be thoughtful consumers of AI tools and content.

- Given the rapid evolution of AI, system leaders struggle to vet AI resources and tools.

Methodology

Bellwether administered a survey to school system leaders in fall 2024. The sample included a mix of traditional public and charter school system leadership. Bellwether received 102 respondents, primarily from traditional public school district leaders.5 The leaders represent school districts in 37 unique states and the District of Columbia, with greater rural representation: 64% of the sample respondents were from rural districts.

To supplement the information from the survey, Bellwether conducted interviews and focus groups with 12 system leaders from November 2024 to December 2024. Like the survey sample, the interview sample had a disproportionally large number of rural school leaders.

Given the small convenience sample and over-representation of rural districts, the findings are not nationally representative but can provide an early look at how school system leaders are approaching AI.

School Leaders Are Cautiously Excited AI Users, But Lack Strategy

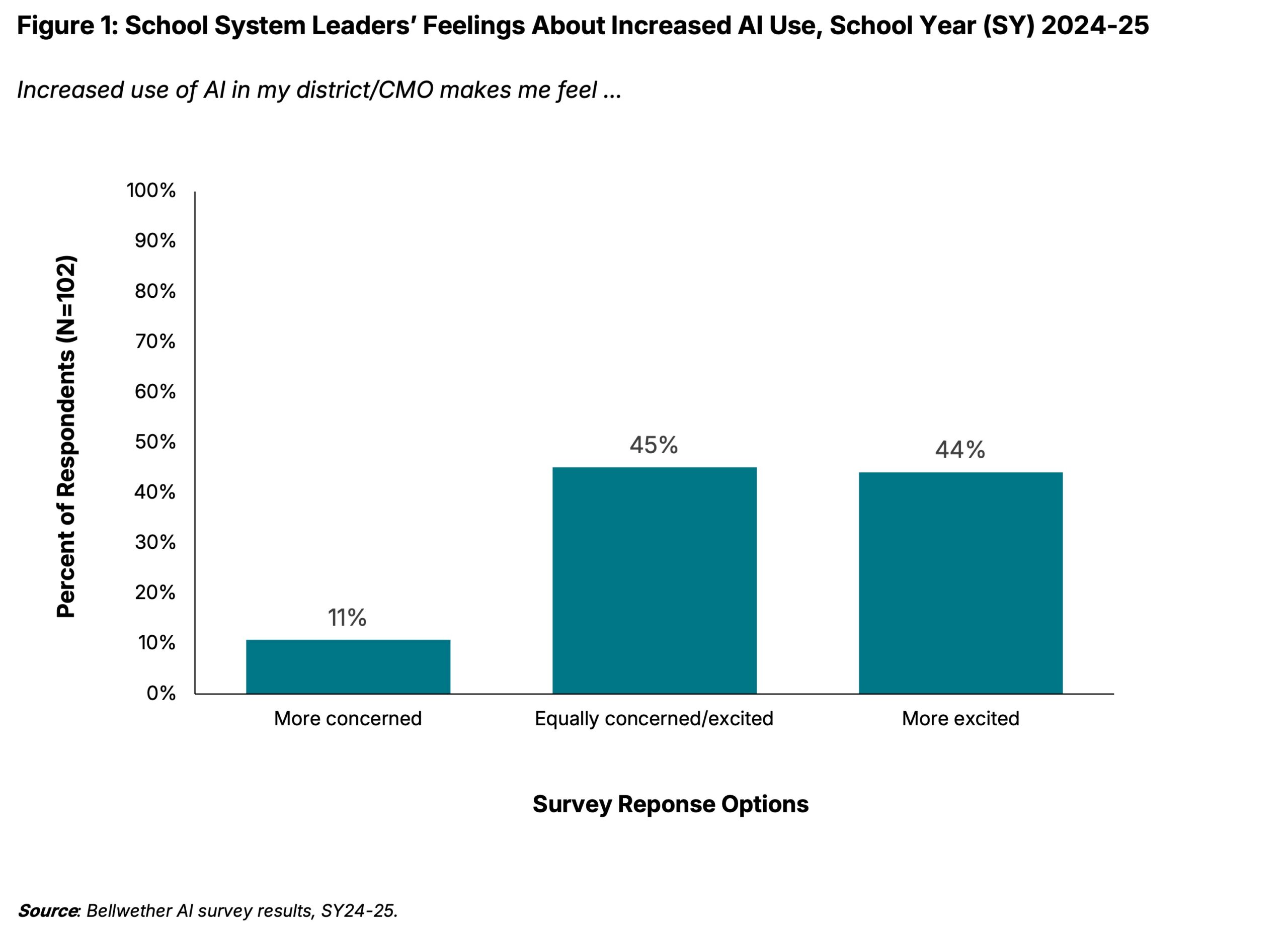

In general, surveyed leaders feel excited or mixed about the use of AI in their school systems (Figure 1). They describe a balancing act between addressing potential challenges and embracing opportunities:

I’m concerned about…

“How [AI] will be abused, but also what are we missing that would benefit us.”6

“Figuring out how to balance appropriate use [of AI] while maintaining academic integrity.”7

“Reliance on AI for decision-making could diminish our critical thinking skills, making it essential to ensure that AI complements rather than replaces human cognition.”8

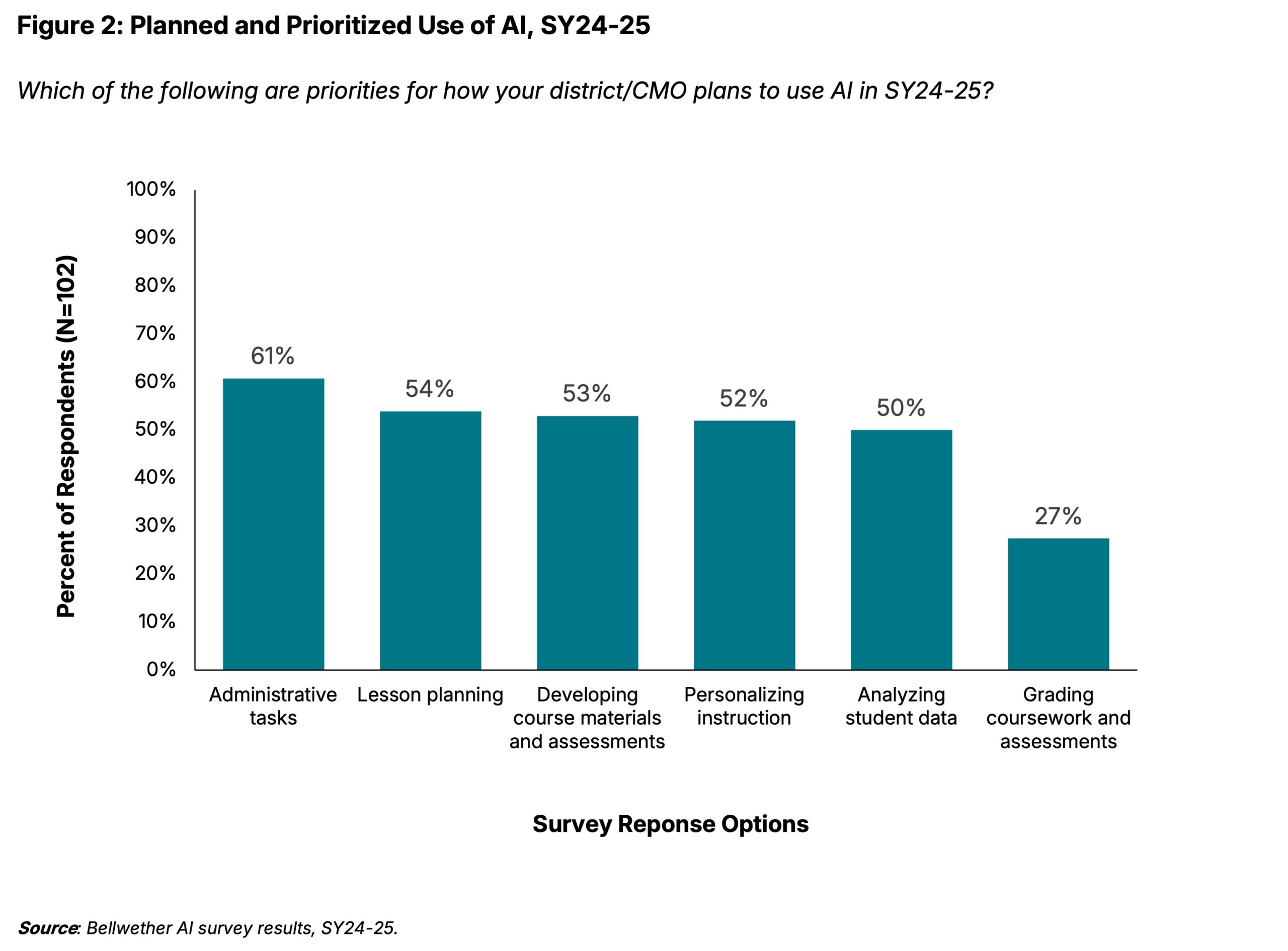

Nearly three-quarters (71%) of leaders had plans to intentionally use AI during SY24-25. Sixty-one percent of leaders anticipated using AI for administrative tasks, while a much smaller percentage (27%) planned to use AI for grading coursework and assessments (Figure 2). In interviews, leaders described using AI for everything from writing drafts of speeches to data analysis to grant writing. Many are sharing how they are using AI with others on their leadership team or with teachers to get staff thinking about how AI could be useful. For example, one administrator described providing staff with an AI summary of a 30-page article he asked them to read before a meeting to demonstrate the time-saving aspects of the tool. Another administrator described having his leadership team use ChatGPT as a brainstorming partner to create a list of restorative practices for the team to discuss as well as to analyze data for the team to identify trends.

These examples demonstrate the excitement and curiosity that many leaders have about AI as well as the lack of systemwide plans; none of the leaders surveyed described having an overarching strategy for integrating AI into teaching and learning across their districts or networks (Sidebar 1).

Sidebar 1: AI may offer unique benefits for rural schools and districts, but they may be even slower to adopt a systemwide approach to AI.

While 71% of survey respondents indicated they have plans to use AI in the upcoming school year, there was a nearly 10-point difference between rural and non-rural system leaders (64% of rural leaders indicated they had plans to use AI, compared to 73% of non-rural leaders).

There are potential uses for AI in all types of schools — district, charter, and private; rural, urban, and suburban; large and small. But there may be particular ways that AI can help solve persistent challenges facing rural school districts. While many rural districts produce educational outcomes that surpass those of more urban and suburban districts,9 rural districts often struggle with distinct challenges such as offering a wide range of courses,10 finding and retaining talented teachers,11 and navigating state policy contexts that do not adequately account for rural districts’ needs.12

The AI use cases noted by leaders in Bellwether’s interviews (e.g., lesson planning, personalized learning, and data analysis) could be particularly powerful in rural schools, since having AI complete these tasks could free up needed capacity for teachers to complete critical human-centered teaching tasks. Yet while AI can be freely accessed online — offering a more leveled playing field for cash-strapped rural districts — the lack of reliable internet in many rural communities poses a real barrier.13

Teachers Are Using AI to Improve Their Own Efficiency

School system leaders see substantial opportunities for AI to save teachers time in two key areas: lesson planning and developing course materials. And while all teachers could benefit from these efficiencies, they may be particularly useful for early-career teachers or teachers in small schools without access to peer collaboration.14

“My main purpose [using AI] is if I can make my staff’s life easier and where it can save them time.” —Superintendent, New Mexico

Surveyed leaders also see an opportunity for AI to reduce the barriers to entering the teaching profession, helping to expand the potential educator workforce. In 2023, nearly nine out of 10 public K-12 schools reported hiring challenges for SY23-24.15 This challenge may be even more acute for particular courses and communities. For example, more than half of schools in rural and town communities had vacancies in foreign language teaching roles, compared with 36% of schools in cities and 37% in suburban communities.16

AI can also help fill some of the gaps that nontraditionally trained teachers may have. One leader explained that many teachers entering the profession through nontraditional pathways struggle to learn how to plan units and lessons and create presentations for elementary and middle school students. “They can use technology to make up some of that difference,” the leader explained. “Instead of spending hours lesson planning, they can give ChatGPT the relevant grade-level and content standards and ask AI questions about what they want to teach and the methods they want to use.”17

Despite some enthusiasm around using AI to help with teaching, surveyed leaders caution that education should continue to be human-centered and that AI cannot replace the need for trained teachers. According to one leader, “We have to make sure that the future still has human educators as the center of our classrooms. I think AI is a game changer that’s going to force more teachers to adopt a student-centered approach. The human educator, the pedagogy expert, is still relevant.”18 Another leader described a concern that teachers could overuse AI in their classrooms, ultimately hurting “the value of a human educator in education.”19

In the future, some administrators would like teachers to use AI for other time-saving tasks beyond lesson planning. For instance, surveyed leaders would like teachers to be able to easily run reports of student data and have the program identify which students need additional support on a particular skill.20 Leaders also see an opportunity, assuming appropriate data protections are in place, for special education staff to save time on individualized education program writing for students.

While leaders are prioritizing using AI to ease the administrative burden on teachers, 52% of the leaders surveyed identified personalized learning as a planned or prioritized use of AI. A few leaders also mentioned using AI to better support students with disabilities. One school leader, for instance, would like to pilot using AI podcast summaries of reading materials to help reinforce for struggling readers what they have read.

Systemwide AI Policies Lag or Offer Limited Guidance for School Communities

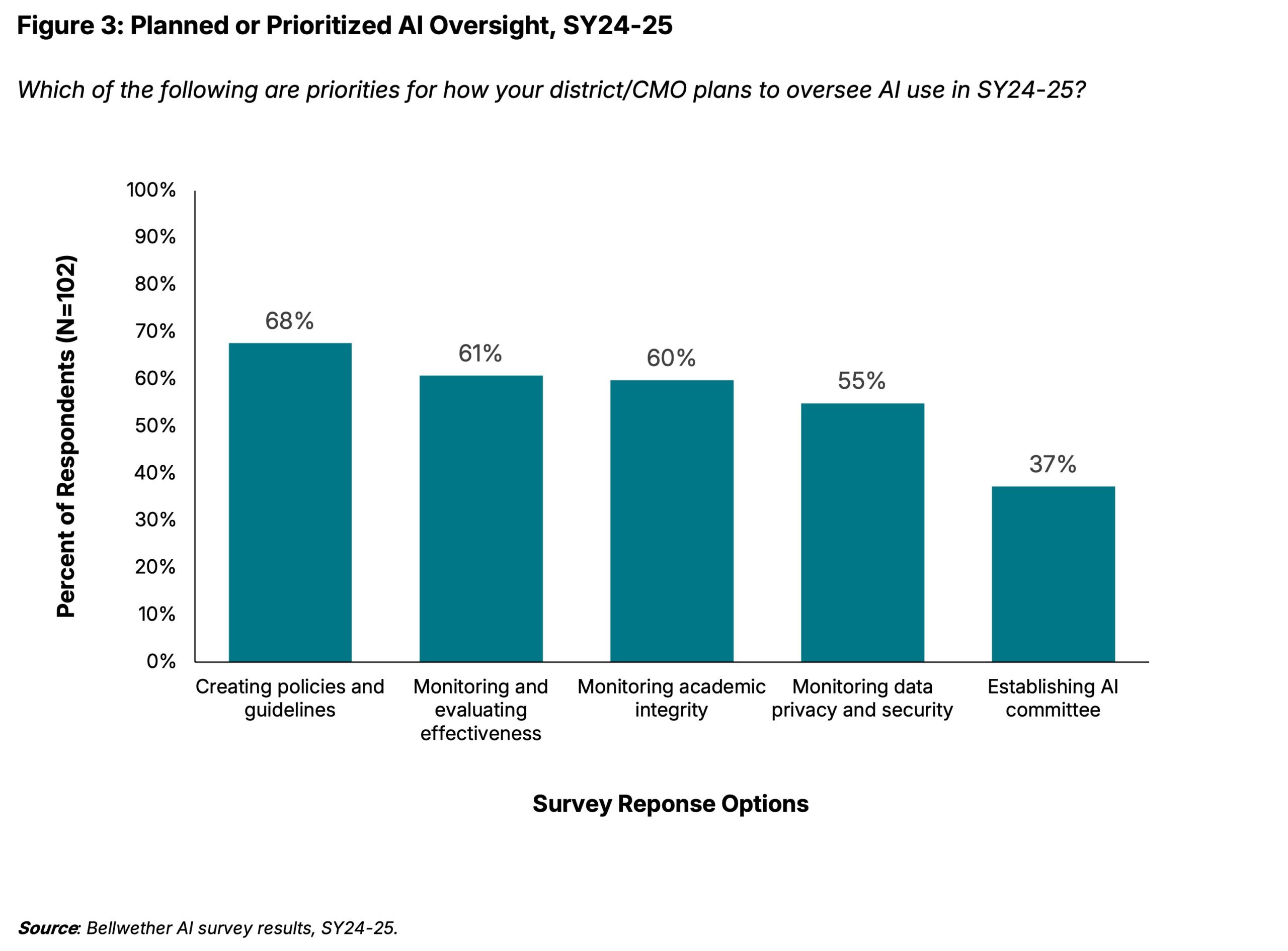

Survey participants were asked about their priorities regarding AI oversight in their respective school systems. More than six in 10 leaders surveyed indicated they were focused on creating policies and guidelines, monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of AI tools, and monitoring academic integrity (Figure 3). Over half of the leaders surveyed (55%) say their district or charter management organization (CMO) has adopted or revised an AI policy in the past two years.21

One source of delay is that school system leaders are using model policies from states and associations as a basis for their policies, and only about half of states have issued guidance on AI use to schools and districts.22 Multiple leaders described waiting for their state or state association to finish a policy that the district would then review, adapt, and adopt. Other leaders noted that the speed at which the technology changes makes it difficult to create specific guardrails around use — by the time an AI policy is adopted, its guidelines may be outdated. Still other leaders say AI is not a high priority right now. However, they acknowledge that it may become a priority once there is an inappropriate use of AI in their district or a neighboring one. One leader in Pennsylvania noted that an AI policy will likely be developed in response to the first instance of inappropriate behavior where “someone will do something that they shouldn’t do, and then it will make it mandatory for others to set guardrails.”

Where AI policies do exist, leaders tend to describe them as vague and minimally useful — much like the state policies, which have been described as “by and large, ambiguous and underdeveloped.”23 One school system leader whose district had an AI policy described it as requiring procedures to be put into place to maintain confidential information.24 For others with policies, they largely focus on academic dishonesty and are silent on issues of bias, data privacy, acceptable use by staff, and other key topics. For instance, one district’s AI policy is embedded within its academic dishonesty policy, which the school leader described as a “super generic plagiarism policy” that “only mentions AI a couple of times.”25

As surveyed leaders think about AI policy development, they favor general policies that would allow for use and innovation. For instance, one district leader described the policy they are currently developing as broad and tool agnostic, focused instead on actions and strategies about how AI could be used.26

School System Leaders Understand the Need to Prepare Students to Use AI Responsibly

Although surveyed administrators are concerned with making sure that students understand AI, they do not have much information about how students are currently using it (Sidebar 2). Some believe there is not much student use; others think that students are using AI primarily for noneducational purposes.

That said, system leaders want to make sure students are prepared for a changing workforce where AI will be more important. One leader said his biggest concern about AI was figuring out “how education needs to change to ensure we are properly equipping our students for the workforce.”27 This challenge can feel even more acute for leaders of systems that serve large populations of Black, Hispanic, and low-income students and/or have long-standing achievement gaps. One such leader explained, “We know that walking onto a college campus, our current alumni are light-years behind their peers. That gap will grow if we don’t teach our students to use AI.”28

Some research suggests this gap is already emerging: Teachers in rural and urban schools and in schools where a majority of students are students of color report receiving less training on AI tools than their peers in suburban or majority-white schools.29 Without training, teachers may be hesitant to incorporate AI into their classrooms — leaving their students underprepared to navigate a job market and world influenced by AI.

Sidebar 2: There are shifting views on AI and academic dishonesty.

While 60% of survey respondents indicate that they plan to monitor students’ AI use for academic integrity, conversations with leaders indicate they are far more concerned about AI’s impact on critical thinking, writing, and other skills than they are about cheating. The concern is “that when students rely on a generative AI tool like ChatGPT to outsource brainstorming and writing, they may be losing the ability to think critically and to overcome frustration with tasks that don’t come easily to them.”30

Many school system leaders acknowledge that cheating has always been a challenge; AI is simply a new way to cheat. As one leader said, “It’s not just about cheating. Cheating isn’t my focus as a superintendent. People have cheated for centuries.”31

Given that “[students] were already cheating, and you didn’t catch them,”32 leaders are now focusing on designing lessons that reduce the likelihood for students to rely on AI to do the work for them and teaching students how to appropriately use the tools.

Amid Rapid Change, Vetting AI Tools is Challenging for School System Leaders

The technology behind AI is changing rapidly, making it difficult for leaders to develop and implement plans to systematically adopt AI into teaching and learning. Surveyed leaders say that, while education has faced technological shifts in the past — such as internet and cell phones — AI feels different. It took time for educators to figure out how to incorporate previous technology shifts in smart ways that prioritize student safety and learning. Some survey participants remember being in the classroom when the internet was first introduced and not knowing how to use it for education. Others mentioned that schools are still grappling with cell phone use. For instance, one leader described thinking that cell phones “would be ubiquitous” in classrooms, but their district, like many others, just passed a cell phone ban.33

One of the biggest challenges system leaders named is vetting AI tools and materials; they describe an overwhelming range of content and tools. As one leader noted, “Thousands of books and articles is too much.”34 Without a strong background in AI, system leaders can find it difficult to evaluate the quality of vendors. Some described “not even knowing the right questions to ask.”35

The difficulty in vetting AI resources also affects staff professional development. Despite wanting to encourage AI use among staff and students, many leaders rely on informally sharing opportunities to increase staff understanding instead of formal professional development opportunities. Some strategies include leaders attending (or sending staff to attend) conferences and then sharing what they learned. Similarly, leaders mentioned capitalizing on informal knowledge-sharing opportunities from other schools or districts they already partner with.

In some cases, this choice of less formal AI professional development is a strategic move to increase teacher buy-in. Given that some teachers are resistant to incorporating AI, leaders are having AI enthusiasts share what they have learned, hoping to build interest among others about how AI could help make teaching easier.36

In other cases, the lack of planned professional development is largely due to a lack of content knowledge about AI. Like vetting tools, some surveyed leaders find it challenging to identify high-quality AI professional development materials. Leaders do not feel qualified to lead the professional development themselves and are reluctant to invest in the costs of bringing in an external vendor to deliver professional development to their teams.

“With every new initiative, you’ve got your good players, and you’ve got those that are trying to make money. I don’t know who the good vendors are to bring in front of our people at this point yet.” —Superintendent, Arkansas

Finally, some leaders simply do not know what they need yet.

Given these challenges, many surveyed school system leaders are adopting a “wait-and-see” approach. Some believe they have time to go slow to make more informed decisions; they cited flexible staff training structures that could allow for changes to their planned professional development to accommodate AI, if needed.

Moreover, none of the surveyed leaders had a systemwide plan for incorporating AI into classroom lessons, and only a few had provided guidance to teachers about what they should or should not be doing with AI in their classrooms.

What Is Next

Ongoing research is needed to understand how these and other issues evolve within school systems as AI technology advances, new tools come to market, and the world continues to adapt. And while Bellwether’s survey offers a glimpse into how a small number of system leaders are thinking about incorporating AI into teaching and learning, it also surfaces several critical needs and questions researchers and policymakers should pay attention to in the following realms:

- Vetting providers.

- Providing professional development for teachers.

- Ensuring AI is not exacerbating existing inequalities.

- Helping students learn to use AI effectively.

- Creating stronger policies that provide real guidance while maintaining flexibility as the field evolves.

- Measuring the impact of AI on student outcomes and/or productivity.

Acknowledgments, About the Authors, About Bellwether

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many experts who gave their time and shared their knowledge with us to inform our work, in particular the many school system leaders who completed the survey and participated in focus groups. Thank you also to the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Raikes Foundation for their financial support of this project.

We would also like to thank our Bellwether colleagues Mary K. Wells, Daniela Torre Gibney, Katrina Boone, Andy Jacob, and Marisa Mission for their input and Alexis Richardson for her support. Thank you to Amy Ribock, Kate Neifeld, Zoe Cuddy, Julie Nguyen, Mandy Berman, and Amber Walker for shepherding and disseminating this work, and to Super Copy Editors.

The contributions of these individuals and entities significantly enhanced our work; however, any errors in fact or analysis remain the responsibility of the authors.

About the Authors

Michelle Croft

Michelle Croft is an associate partner at Bellwether in the Policy and Evaluation practice area. She can be reached at michelle.croft@bellwether.org.

Nora Weber

Kelly Robson Foster

Kelly Robson Foster is a senior associate partner at Bellwether in the Policy and Evaluation practice area. She can be reached at kelly.foster@bellwether.org.

Bellwether is a national nonprofit that exists to transform education to ensure systemically marginalized young people achieve outcomes that lead to fulfilling lives and flourishing communities. Founded in 2010, we work hand in hand with education leaders and organizations to accelerate their impact, inform and influence policy and program design, and share what we learn along the way. For more, visit bellwether.org.

Endnotes

- “Introducing ChatGPT,” OpenAI, November 30, 2022, https://openai.com/index/chatgpt/.

- Daniel Mollenkamp, “Will AI Shrink Disparities in Schools, or Widen Them?,” EdSurge, August 19, 2024, https://www.edsurge.com/news/2024-08-19-will-ai-shrink-disparities-in-schools-or-widen-them.

- Alex Singla, Alexander Sukharevsky, Lareina Yee, Michael Chui, and Bryce Hall, “The State of AI in Early 2024: Gen AI Adoption Spikes and Starts to Generate Value,” McKinsey, May 30, 2024, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai.

- See, for example: “The Value of AI in Today’s Classrooms,” Walton Family Foundation, June 11, 2024, https://www.waltonfamilyfoundation.org/learning/the-value-of-ai-in-todays-classrooms; Melissa Kay Diliberti, Heather L. Schwartz, Sy Doan, Anna Shapiro, Lydia R. Rainey, and Robin J. Lake, “Using Artificial Intelligence Tools in K–12 Classrooms,” RAND, April 17, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-21.html; Common Sense Media, “Teen and Young Adult Perspectives on Generative AI: Patterns of Use, Excitements, and Concerns,” Common Sense Media, Hopelab, and the Center for Digital Thriving at Harvard Graduate School of Education, June 3, 2024, https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/teen-and-young-adult-perspectives-on-generative-ai-patterns-of-use-excitements-and-concerns; Olivia Sidoti and Jeffrey Gottfried, “About 1 in 5 U.S. Teens Who’ve Heard of ChatGPT Have Used It for Schoolwork,” Pew Research Center, November 16, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/11/16/about-1-in-5-us-teens-whove-heard-of-chatgpt-have-used-it-for-schoolwork/.

- The survey response rate was approximately 1%, such that it is not a nationally representative sample.

- Open-ended survey response.

- Open-ended survey response.

- Open-ended survey response.

- Daniel Showalter, Sara L. Hartman, Karen Eppley, Jerry Johnson, and Bob Klein, “Why Rural Matters: Centering Equity and Opportunity,” The National Rural Education Association, 2023, https://wsos-cdn.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/uploads/sites/18/10-26WRMReport2023_DIGITALFINAL.pdf.

- See, for example: Douglas J. Gagnon and Marybeth J. Mattingly, “Limited Access to AP Courses for Students in Smaller and More Isolated Rural School Districts,” Carsey Research, Carsey School of Public Policy at University of New Hampshire, 2015, https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1234&context=carsey; Suzanne Graham, “Students in Rural Schools Have Limited Access to Advanced Mathematics Courses,” Paper 89, The Carsey Institute at the Scholars’ Repository, 2009, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254721637_Students_in_rural_schools_have_limited_access_to_advanced_mathematics_courses.

- Richard M. Ingersoll and Henry Tran, “The Rural Teacher Shortage,” Kappan, October 30, 2023, https://kappanonline.org/rural-teacher-shortage-ingersoll-tran/.

- Showalter, Hartman, Eppley, Johnson, and Klein, “Why Rural Matters: Centering Equity and Opportunity.”

- Gabriel E. Hales and Keith N. Hampton, “Rural Students’ Access to Wi-Fi Is in Jeopardy as Pandemic-Era Resources Recede,” The 74, April 24, 2024, https://www.the74million.org/article/rural-students-access-to-wi-fi-is-in-jeopardy-as-pandemic-era-resources-recede/; Janessa M. Graves, Demetrius A. Abshire, Solmaz Amiri, and Jessica L. Mackelprang, “Disparities in Technology and Broadband Internet Access Across Rurality: Implications for Health and Education,” Family & Community Health 44, no. 4 (2021): 257–265, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8373718/; Anna Merod, “Why E-Rate’s Future Is Now in the Hands of the Supreme Court,” K–12 Dive, November 27, 2024, https://www.k12dive.com/news/supreme-court-fcc-consumers-research-e-rate/733941/.

- “Supporting Rural Educators: Professional Learning Through Rural Education Collaboratives” (blog), https://www.ed.gov/about/ed-offices/oese/blog/supporting-rural-educators-professional-learning-through-rural-education-collaboratives, 2019.

- “Most Public Schools Face Challenges in Hiring Teachers and Other Personnel Entering the 2023-24 Academic Year,” release, National Center for Education Statistics, October 17, 2023, https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/10_17_2023.asp.

- National Center for Education Statistics, “Difficulty Hiring Teachers in Rural Areas,” Condition of Education, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, 2024, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/llc#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20of%20public%20schools,and%2036%20percent%20in%20cities.

- Ohio superintendent, focus group.

- Texas superintendent, focus group.

- Survey open-ended response.

- Texas superintendent, focus group.

- This finding is somewhat higher than a previous CRPE/RAND survey that found 5% had policies in fall 2023 with 31% planning to develop policies in 2023–24. See Diliberti, Schwartz, Doan, Shapiro, Rainey, and Lake, “Using Artificial Intelligence Tools in K–12 Classrooms”; Bree Dusseault, “Districts and AI: Tracking Early Adopters and What This Means for 2024–25,” CRPE, October 2024, https://crpe.org/districts-and-ai-tracking-early-adopters-and-what-this-means-for-2024-25/.

- “Learning Systems: Opportunities and Challenges of Artificial Intelligence—Enhanced Education,” in Amy Chen Kulesa, Michelle Croft, Brian Robinson, Mary K. Wells, Andrew J. Rotherham, and John Bailey, “Learning Systems: Shaping the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Education,” Bellwether, September 24, 2024, https://bellwether.org/publications/learning-systems/. Note: Since publication, Louisiana has adopted guidance, according to the Teach AI “AI Policy Tracker,” 2024, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1J9CSLfbUoMRrGh0bPWoyPKMcGe41rRbllernzQXAffY/edit?gid=0#gid=0.

- Bree Dusseault, “New State AI Policies Released: Signs Point to Inconsistency and Fragmentation,” CRPE, March 2024, https://crpe.org/new-state-ai-policies-released-inconsistency-and-fragmentation/. See also Jeremy Roschelle, Judi Fusco, and Pati Ruiz, “Review of Guidance from Seven States on AI in Education,” Digital Promise, February 2024, https://digitalpromise.dspacedirect.org/items/a3d38366-be66-4908-b40a-c9cda146ca2a.

- Michigan superintendent, focus group.

- Arkansas superintendent, focus group.

- Texas superintendent, focus group.

- Open-ended survey response.

- Executive Director of a CMO in DC, focus group.

- Melissa Kay Diliberti, Heather L. Schwartz, Sy Doan, Anna Shapiro, Lydia R. Rainey, and Robin J. Lake, “Using Artificial Intelligence Tools in K–12 Classrooms,” RAND, April 17, 2024, Figure 7, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-21.html.

- Jessica Grose, “What Teachers Told Me About A.I. in School,” The New York Times, August 14, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/14/opinion/ai-schools-teachers-students.html.

- Michigan superintendent, focus group.

- Texas superintendent, focus group.

- Arianna Prothero, Lauraine Langreo, and Alyson Klein, “Which States Ban or Restrict Cellphones in Schools?,” Education Week, June 28, 2024, https://www.edweek.org/technology/which-states-ban-or-restrict-cellphones-in-schools/2024/06; Shauneen Miranda, “U.S. Department of Education Pints States, Schools to Set Policies on Cellphone Use,” Stateline, December 4, 2024, https://stateline.org/2024/12/04/dc/u-s-education-department-pings-states-schools-to-set-policies-on-cellphone-use/.

- Executive Director of a CMO in DC, focus group.

- New Mexico superintendent, focus group.

- South Dakota superintendent, focus group.